kottke.org posts about books

Nassim Taleb asserts that, on average, old technologies have longer life expectancies than younger technologies, which helps explain why books are still around and CD-ROM magazines aren’t.

For example: Let’s assume the sole information I have about a gentleman is that he is 40 years old, and I want to predict how long he will live. I can look at actuarial tables and find his age-adjusted life expectancy as used by insurance companies. The table will predict he has an extra 44 years to go; next year, when he turns 41, he will have a little more than 43 years to go.

For a perishable human, every year that elapses reduces his life expectancy by a little less than a year.

The opposite applies to non-perishables like technology and information. If a book has been in print for 40 years, I can expect it to be in print for at least another 40 years. But — and this is the main difference — if it survives another decade, then it will be expected to be in print another 50 years.

This is adapted from Taleb’s recent book, Antifragile. Anyone read this yet? I really liked The Black Swan.

Sesame Street did a series of tweets the other day in the style of The Monster at the End of This Book, which is a favorite of mine and my kids.

Grover: That tweet, did it say there was a MONSTER at the end of it?

Grover: It did? Well, please do not retweet that tweet!

Grover: YOU RETWEETED THE TWEET!

In a new ebook called Epic Fail: Bad Art, Viral Fame, and the History of the Worst Thing Ever published by The Millions, Mark O’Connell traces the history of futile culture-making.

In this original e-book from the online magazine The Millions, Mark O’Connell, one of our funniest and most adroit young literary critics, sets out to answer these questions. He uncovers the historical context for our affinity for terrible art, tracing it back to Shakespeare and discovering the early-20th-century novelist who was dinner-party fodder for C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. He tracks the ascendancy of a once esoteric phenomenon into the mainstream, where “what Marshall McLuhan famously referred to as the Global Village now anoints a new Global Village Idiot every other week.” He offers in-depth accounts of Rebecca Black, Tommy Wiseau, and the “Monkey Jesus”… and he probes the roots of his own obsession with terrible art. In this charming and insightful investigation into why we laugh, O’Connell not only spins a good tale, but he emerges as our leading analyst of the “so bad it’s good” phenomenon. And his discoveries may make you think twice the next time someone passes along a link to the latest, greatest “Epic Fail.”

Here’s an excerpt.

Tom Standage’s upcoming book, which we have to unfairly wait until October for, is called Writing on the Wall: Social Media — The First Two Thousand Years.

Papyrus rolls and Twitter have much in common: They were their generation’s signature means of “instant” communication. Indeed, as Tom Standage reveals in his scintillating new book, social media is anything but a new phenomenon. From the papyrus letters that Cicero and other Roman statesmen used to exchange news across the Empire to the rise of hand-printed tracts of the Reformation to the pamphlets that spread propaganda during the American and French revolutions, Standage chronicles the increasingly sophisticated ways people shared information with each other, spontaneously and organically, down the centuries.

I kinda wish he would have called it The Victorian Internet 2: Electric Boogaloo. A couple of excerpts/adaptations from the book have already made it out into the world: social networking in 17th century English coffeehouses and how Martin Luther’s message went viral.

In The Hobbit, Bilbo Baggins signs a contract with a company of dwarves to serve as their burglar in their quest to reclaim the Lonely Mountain from a dragon. Lawyer James Daily analyzed the contract in detail for Wired.

Even in the book’s version we see an issue: the dwarves accept Bilbo’s “offer” but then proceed to give terms. This is not actually an acceptance but rather a counter-offer, since they’re adding terms. In the end it doesn’t matter because Bilbo effectively accepts the counter-offer by showing up and rendering his services as a burglar, but the basic point is that the words of a contract do not always have the legal effect that they claim to have. Sometimes you have to look past the form to the substance.

See also How valid is the implied legal advice in Jay-Z’s “99 Problems”?

Here’s just one of the many odd revelations from Lawrence Wright’s book on Scientology that’s coming out this week:

John Travolta began taking Scientology courses before his audition for the TV show Welcome Back, Kotter, and fellow students pointed in the direction of ABC Studios to telepathically communicate: ‘We want John Travolta for the part.’ (He got the part.)

Thankfully, Horshack got the part the old-fashioned way. He raised his hand and said, oooooohhhhh! oooooohhhhh! oooooohhhhh!

If Dr. Seuss books were titled more like academic journal articles, that might look something like this:

(thx, jeffrey)

In a profile this summer from Le Monde, Christopher Tolkien, the 88 year-old son of J.R.R. Tolkien blasted Peter Jackson and The Lord of the Rings / The Hobbit movies. (If you can’t speak French, you should see the translation of the profile.) Tolkien, who drew the maps for the Lord of the Rings books, has spent most of his life protecting the legacy of his father’s works, and the movies are, apparently, a bridge too far.

Invited to meet Peter Jackson, the Tolkien family preferred not to. Why? “They eviscerated the book by making it an action movie for young people aged 15 to 25,” Christopher says regretfully. “And it seems that The Hobbit will be the same kind of film.”

This divorce has been systematically driven by the logic of Hollywood. “Tolkien has become a monster, devoured by his own popularity and absorbed into the absurdity of our time,” Christopher Tolkien observes sadly. “The chasm between the beauty and seriousness of the work, and what it has become, has overwhelmed me. The commercialization has reduced the aesthetic and philosophical impact of the creation to nothing. There is only one solution for me: to turn my head away.”

(via ★Stellar)

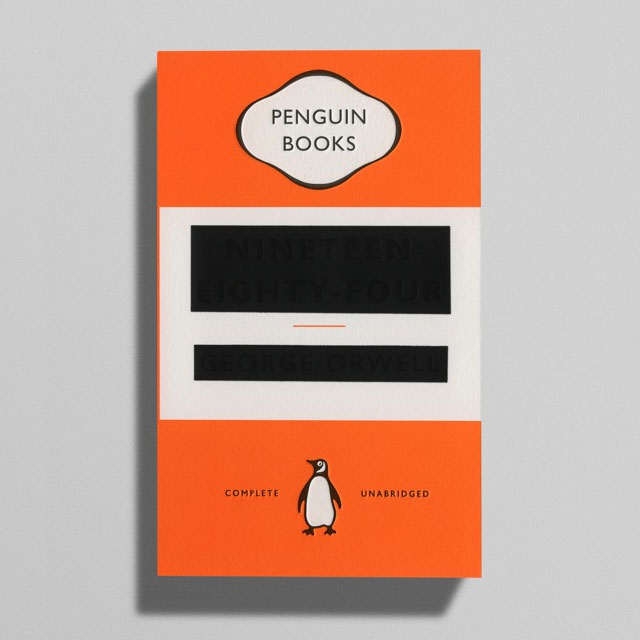

A new series of George Orwell’s books are being published by Penguin and this is the cover for 1984:

Cover design by David Pearson…more covers from the same series here. (via @torrez)

The NY Times asked a bunch of designers for their favorite book cover designs of 2012. Lots of nice work here.

Oh ho, what’s this? Choire Sicha’s book is available for pre-order on Amazon. It’s called Very Recent History: An Entirely Factual Account of a Year (c.2009 A.D.) in a Large City. I don’t know what the book is about beyond that, but Choire wrote a bit about writing and publishing in his non-announcement of it, the book.

In 2007, Kyle Cassidy published a book called Armed America: Portraits of Gun Owners in Their Homes. He asked his subjects a simple question: Why do you own a gun?

Cassidy traveled over 20,000 miles, crisscrossing the country to meet with gun owners in their homes. Cassidy’s photo essays create a powerful, thought provoking and sometimes startling view of gun ownership in the U.S. These “everyman” portraits, and the accompanying views of gun owners, fashion a riveting and provocative hardcover book.

From book’s web site, a sampling of images and answers:

Paul: My family had guns the whole time I was a kid. then i went off and joined the army and went away and come back. I have guns now largely for the same reason I have fire extinguishers in the house and spare tires in the car. I’m a self reliant kind of guy. and there could come a time when I need to protect my family and i’m a self reliant kind of guy.

Beth: I have one for self protection. I was raised to never rely on anyone else to protect me or watch my back. It took me a year to pick out one that I liked.

Bashir: I just think it’s a good thing to have

Joe: The first time I was introduced to guns was when I was 5 years old; hunting with my dad, grandfather and uncle. I remember my dad shooting a ringneck pheasant and a rabbit. I carried those two animals until I thought my arms were going to fall off. As a little guy, that made a great impression on me. I’ve hunted all of my life; in Pennsylvania, Idaho, Colorado and Maine. I have a tremendous respect for life, especially wildlife. It never ceases to amaze me how much satisfaction I get from just simply being in the Great Outdoors, whether I make a kill or not.

(via virtual memories)

The BBC is making a 6-part miniseries out of Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell.

For those unfamiliar with the book, it’s a sweeping fantasy novel set during the Napoleonic Wars where two magicians have emerged in Britain. As well as telling the story of their rivalry, it also details an amazing alternate history where the North of England was the dominion of a magical overlord known as the Raven King, and pulls in many notable historical characters.

Can’t wait…I loved JS&MN.

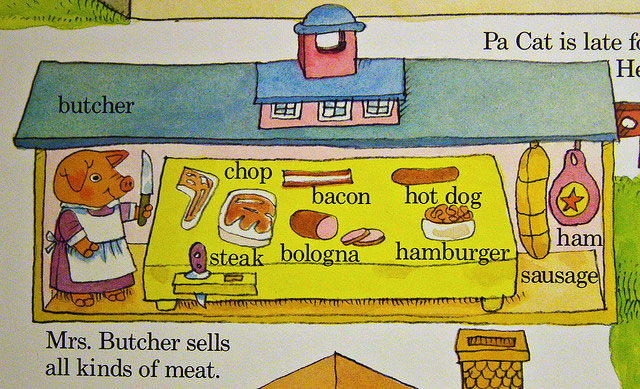

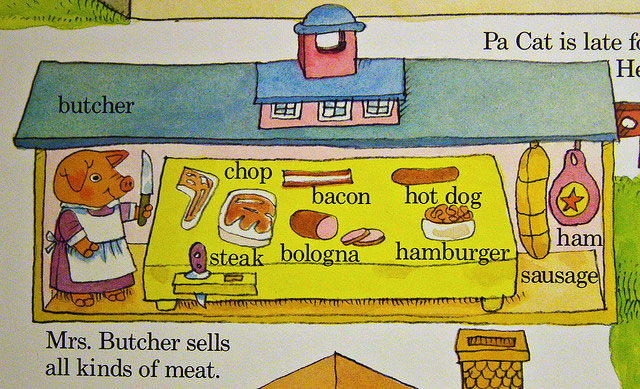

From a planning and transportation professional, a deconstruction of Busytown, the fictional town that features in many of Richard Scarry’s children’s books, including What Do People Do All Day?, Busy, Busy Town, and my personal favorite, Cars and Trucks and Things That Go.

Scarry moved to Switzerland in 1968, and if nothing else, Swiss architecture permeates the old town center of What Do People Do All Day. The Town Hall of Busytown on the cover is nothing if not Tudor. There is a small gate through which a small car is driving. Something to note about the vehicles in Busytown is that they are all just the right size for the number of passengers they carry. The Bus on the cover is full, with a hanger-on. The taxi holds one driver in the front and one passenger in the rear. The police officer (Seargant Murphy) is riding a motorcycle. When he has a passenger, the motorcycle always has a sidecar. Similarly, each window in town has someone in it, sometimes more than one person. Of course, this is a busy town, so the activity makes sense. The cover of this includes the grocery store, butcher, and baker (no supermarkets in 1968 Busytown), one block in front of Town Hall. One thing to note about the Butcher is that he is a pig, and clearly butchering sausages.

The self-slaughter and cannibalism of the pigs is documented in Merlin Mann’s Scarry Pigs in Peril Flickr set.

See also this examination of What Do People Do All Day?:

Nonetheless, Busytown is a place that works. Literally, in that it appears to enjoy full employment, and also in the sense that it has few obvious social problems. The police force, consisting of Sergeant Murphy, Policeman Louie and their chief, is charged with ‘keeping things safe and peaceful’ and ‘protecting the townspeople from harm’, which appears to largely consist of directing traffic, ticketing hoons and apprehending the town’s notorious thief, Gorilla Banana [sic].

Now of course one could opine that it’s in fact diffuse surveillance and self-surveillance that keep such remarkable order. All those open windows and doors, all that neighbourly cheerfulness, have a slightly sinister edge to them, if you’re inclined to look for it, as do the lengths that some of the citizens will go to in order to promote proper behaviour amongst children.

(via @inthefade)

Update: And here’s another installment of the Busytown police blotter.

Traffic officer reported busiest traffic jam ever at intersection of Main and Hippopotamus. Gridlock started when a peanut car stalled in the intersection and the elderly cricket driver was unable to restart the vehicle. Officer and several drivers assisted the elderly cricket in moving his vehicle to the side of the road, where it was then struck by an alligator car driven by a female rabbit. Officer reported smelling alcohol in the female rabbit’s breath and placed her in handcuffs until backup arrived. Officers then cleared the jam with the aid of two tow trucks.

(thx, elaine)

And so it begins, the end of the year lists. Love ‘em or hate ‘em, you’ve got to, um, … I’ve got nothing here. You either love them or hate them. Anyway, the NY Times’ list of the 100 notable books of the year is predictably solid and Timesish.

BRING UP THE BODIES. By Hilary Mantel. (Macrae/Holt, $28.) Mantel’s sequel to “Wolf Hall” traces the fall of Anne Boleyn, and makes the familiar story fascinating and suspenseful again.

BUILDING STORIES. By Chris Ware. (Pantheon, $50.) A big, sturdy box containing hard-bound volumes, pamphlets and a tabloid houses Ware’s demanding, melancholy and magnificent graphic novel about the inhabitants of a Chicago building.

I absolutely demolished Bring Up the Bodies over Thanksgiving break and loved it. I haven’t had a chance to sit down with Building Stories yet, but that massive and gorgeous collection is a steal at $28 from Amazon. And as far as lists go, another early favorite is Tyler Cowen’s list of his favorite non-fiction books of the year. Cowen is a demanding reader and I always find something worth reading there. (via @DavidGrann)

In 2004, Liam Callanan published a book called The Cloud Atlas that takes place in Alaska near the end of World War II. Also in 2004, David Mitchell published a book called Cloud Atlas that is told in six stories that unfold, Matryoshka-like, over a period of 200 years. Mitchell’s book was recently adapted into a blockbuster film of the same name by the Wachowskis & Tom Tykwer and starring Tom Hanks & Halle Berry, but Callanan has been affected by the movie as well.

1. My website, cloudatlas.com, was hacked by Russians and blacklisted by Google.

2. My novel, The Cloud Atlas, zoomed to a triple-digit Amazon ranking without my having to email-as I did back when my novel was first published-a single parent, aunt, cousin, neighbor, classmate, ex-girlfriend, former teacher or current student and beg them to buy the book instead of “waiting until the library gets a copy,” as a friend promised he would.

3. Instead, I get a lot of email, from loads more readers than I used to.

4. Including one at 12:14 a.m. this week from someone who had accidentally checked my book out of the library, and was still reading it.

Callanan’s experience aside, I am bummed that Cloud Atlas (the film) did not do better at the box office. It was daring, engaging, and inventive. Not everyone’s cup of tea certainly, but not as weird/challenging as everyone thought it might be. (via the awl: weekend companion)

In their book Store Front: The Disappearing Face of New York, James and Karla Murray are documenting the changing commercial facade of NYC’s streets. A recent post on their blog focuses on a strip of Bleecker St between 6th and 7th Avenues in the West Village. This is Murray’s old location circa 2001, before they moved across the street into a bigger space, expanded that space, and opened an adjacent restaurant:

I moved to the West Village in 2002 and, after a few stops in other neighborhoods around the city, moved back a couple years ago. Walking around the neighborhood these days, I’m amazed at how much has changed in 10 years. Sometimes it seems as though every single store front has turned over in the interim. (via @kathrynyu)

I wondered how long it would be before someone connected Facebook and especially Twitter with the idea of extractive and inclusive economic systems forwarded by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson in Why Nations Fail. The winner, in a delightfully over-the-top fashion, is David Heinemeier Hansson from 37signals.

Twitter started out life as a wonderfully inclusive society. There were very few rules and the ones there were the people loved. Thou shall be brief, retweet to respect. Under this constrained freedom, Twitter prospered and grew rapidly for the joy of all.

Budding entrepreneurs built apps that made life better for everyone. Better, in fact, than many of Twitter’s own attempts. They competed for attention on a level playing field and the very best rose to the top. Users saw that this was good and rewarded Twitter with their attention. Twitter grew.

Unfortunately this inclusive world was not meant to last. From the beginning, an extractive time bomb was ticking. One billion dollars worth of eagerness for return. Hundreds and hundreds of hungry mouths to feed in a San Francisco lair.

And thus began Twitter’s descent into the extractive.

Chrystia Freeland provided the gist of the book in a NY Times essay earlier in the fall:

Extractive states are controlled by ruling elites whose objective is to extract as much wealth as they can from the rest of society. Inclusive states give everyone access to economic opportunity; often, greater inclusiveness creates more prosperity, which creates an incentive for ever greater inclusiveness.

Of the current 200 nations in the world, the British have invaded all but 22 of them. The lucky 22 include Sweden, Luxembourg, Mongolia, Bolivia, and Belarus. The full analysis is available in Stuart Laycock’s book, All the Countries We’ve Ever Invaded.

Stuart Laycock, the author, has worked his way around the globe, through each country alphabetically, researching its history to establish whether, at any point, they have experienced an incursion by Britain.

Only a comparatively small proportion of the total in Mr Laycock’s list of invaded states actually formed an official part of the empire.

The remainder have been included because the British were found to have achieved some sort of military presence in the territory — however transitory — either through force, the threat of force, negotiation or payment.

Incursions by British pirates, privateers or armed explorers have also been included, provided they were operating with the approval of their government.

The US currently has military personnel stationed in all but 43 countries.

For instance, as of Sept. 30, 2011, there were 53,766 military personnel in Germany, 39,222 in Japan, 10,801 in Italy and 9,382 in the United Kingdom. That makes sense. But wait, scanning the list, you also see nine troops in Mali, eight in Barbados, seven in Laos, six in Lithuania, five in Lebanon, four in Moldova, three in Mongolia, two in Suriname and one in Gabon.

But the presence in most of those countries is due to diplomatic usage of military personnel. (thx, aaron)

In October 2011, after 20 years of living legally in the United States, Atanas Entchev and his 21-year-old son were detained by the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, given orange jumpsuits to wear, and held for 65 days. Entchev is writing a book about his experience called My American Lemonade.

Day after day from my bunk, I listened to the immigration stories of my roommates. We all had one. Mine involved over 20 years of countless dollars spent on lawyers who would help me navigate the paperwork and court dates necessary for immigration, based on my request for political asylum. Meanwhile I strived to be tops in my field, starting with a presidential certificate from George H. W. Bush and receiving an Outstanding Professor designation from INS, ICE’s predecessor agency. I started my own company, paid taxes, and raised two children here. But that obviously wasn’t enough. I had failed at giving me and my family what we wanted most: U.S. citizenship. I dug deep, used what my family had taught me about resolve and hope, and thought a lot about my past to remind myself why I’d left Bulgaria. Why I’d bothered. The irony was especially palpable to me lying in that bunk, recalling the moment I knew for sure I must leave.

Entchev is one of kottke.org’s most thoughtful readers…he’s been sending email, links, and typo corrections regularly for more than four years now. From what I understand, he’s completed a book proposal consisting of the first three chapters and is looking for an agent. If you can help him out in that regard, drop him a line.

Here’s a look at a new book based on the diary of Jim Henson called Imagination Illustrated. Here’s the foreword by his daughter Lisa and the first few pages:

Love this idea, BTW…embeddable book excerpts. More like this, please. Actually, if I were Amazon I would make Kindle previews embeddable with a big old “buy the full book at Amazon” button on the last page of the excerpt and tie it in with the Associates Program. Apparently they did offer this once upon a time but not anymore.

I loved this profile of novelist Hilary Mantel written by Larissa MacFarquhar. Not just for the subject matter but the lyrically novelistic way in which it’s written.

During this time, she discovered that her house was haunted. It wasn’t only she who felt it-she overheard adults talking about the ghosts as well. She realized that they were as frightened as she was, and were helpless to protect her. She already understood that the world was denser and more crowded than her senses could perceive: there were ghosts, but even those dead who were not ghosts still existed; she was used to hearing talk in which family members alive and dead were discussed without distinction. The dead seemed to her only barely dead.

Until she was twelve or so, she was deeply religious. “When you’re inculcated with religion at such an early age, or when you’re receptive to it, as I was, you become preoccupied with the unseen reality,” she says. “This other world, the next world, to me in my childhood seemed just as real as the world I was living in. It wasn’t that I had a mental picture of it — it was that I never questioned its existence. I used to conduct a lot of imaginary conversations with God. I don’t think Jesus was any less real to me than my aunts and uncles; the fact that I happened not to be able to see him was pretty irrelevant to me.”

She felt, as a child, in a permanent state of sin. There was something terribly wrong about her, for which she was to blame, but which she had only limited ability to change. Catholic guilt continued to grip her even after she stopped believing in God. Her family’s misery was encompassing and bewildering, and was it not likely that she was responsible for making her parents so unhappy? Might they not, without her, have a chance at a better life? But these suspicions were not so powerful as the effect of a thing that happened to her one day that she cannot explain.

That “thing that happened” was seeing… well, I don’t want to spoil it. Mantel wrote Wolf Hall, a recent favorite of mine, and a few days after this profile ran in the New Yorker, she won the Man Booker Prize for her new novel, Bring Up the Bodies.

Our small corner of the internet freaked out yesterday when Linn Nygaard noticed that all her books had been wiped from her Kindle and her Amazon account had been closed. Nygaard’s account and books have since been restored but the incident has caused many to remember that, oh yeah, the Kindle is more of a Blockbuster Video-like rental store than a reading device. To that end, Zachary West has posted instructions for converting all of your DRM’d Kindle books into a non-DRM format that you can read on any number of devices.

Following up on her piece in the New Yorker on how hedge fund billionaires have become disillusioned with President Obama, Chrystia Freeland says that the 1% are repeating a mistake made many times throughout history of moving from an inclusive economic system to an extractive one.

Extractive states are controlled by ruling elites whose objective is to extract as much wealth as they can from the rest of society. Inclusive states give everyone access to economic opportunity; often, greater inclusiveness creates more prosperity, which creates an incentive for ever greater inclusiveness.

Freeland is riffing on an argument forwarded by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson in Why Nations Fail. Their chief example cited by Freeland is that of Venice:

In the early 14th century, Venice was one of the richest cities in Europe. At the heart of its economy was the colleganza, a basic form of joint-stock company created to finance a single trade expedition. The brilliance of the colleganza was that it opened the economy to new entrants, allowing risk-taking entrepreneurs to share in the financial upside with the established businessmen who financed their merchant voyages.

Venice’s elites were the chief beneficiaries. Like all open economies, theirs was turbulent. Today, we think of social mobility as a good thing. But if you are on top, mobility also means competition. In 1315, when the Venetian city-state was at the height of its economic powers, the upper class acted to lock in its privileges, putting a formal stop to social mobility with the publication of the Libro d’Oro, or Book of Gold, an official register of the nobility. If you weren’t on it, you couldn’t join the ruling oligarchy.

The political shift, which had begun nearly two decades earlier, was so striking a change that the Venetians gave it a name: La Serrata, or the closure. It wasn’t long before the political Serrata became an economic one, too. Under the control of the oligarchs, Venice gradually cut off commercial opportunities for new entrants. Eventually, the colleganza was banned. The reigning elites were acting in their immediate self-interest, but in the longer term, La Serrata was the beginning of the end for them, and for Venetian prosperity more generally. By 1500, Venice’s population was smaller than it had been in 1330. In the 17th and 18th centuries, as the rest of Europe grew, the city continued to shrink.

BTW, Acemoglu and Robinson have been going back and forth with Jared Diamond about the latter’s geographical hypothesis for national differences in prosperity forwarded in Guns, Germs, and Steel. I read 36% of Why Nations Fail earlier in the year…I should pick it back up again.

Gentlemen of Bacongo is a book of photography by Daniele Tamagni documenting a group of men from the Congo who dress in designer suits. Meet Le Sapeurs.

Photographer Daniele Tamagni’s new book Gentlemen of Bacongo captures the fascinating subculture of the Congo in which men (and a few women) dress in designer and handmade suits and other luxury items. The movement, called Le Sape, combines French styles from their colonial roots and the individual’s (often flamboyant) style. Le Sapeurs, as they’re called, wear pink suits and D&G belts while living in the slums of this coastal African region.

In interviews with some notable sapeurs, Tamagni unearths the complex and varied rules and standards of Le Sape, short for Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes, or the Society of Tastemakers and Elegant People. Sapeur Michel comments on the strange combination of poverty and fashion, “A Congolese sapeur is a happy man even if he does not eat, because wearing proper clothes feeds the soul and gives pleasure to the body.”

Solange Knowles recently shot Losing You in South Africa and it features many gentlemen of Le Sape. Tamagni went along as an advisor and photographed Solange along the way. (via @youngna)

To celebrate the release of his new novel, Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore, Robin Sloan is doing two related events at the Center for Fiction in NYC.

Second thing first: At 7pm on Thu, Oct 4, there will be a launch party at the Center for Fiction hosted by Farrar, Straus and Giroux and Electric Literature. RSVP here.

But before the party, Robin will be interviewing a variety of people over a 24-hour period and streaming the whole thing online. I am one of the scheduled interviewees and I have no idea what we’ll talk about. But because my slot is right before the party starts, after almost 20 non-stop hours of Robin interviewing people, it’s possible we’ll just change into our sweatpants, split a pint of Cherry Garcia, and spoon on the couch.

A selection of previously uncollected essays from David Foster Wallace is coming out in book form in November.

Both Flesh and Not gathers 15 essays never published in book form, including “Federer Both Flesh and Not,” considered by many to be his nonfiction masterpiece; “The (As it Were) Seminal Importance of Terminator 2,” which deftly dissects James Cameron’s blockbuster; and “Fictional Futures and the Conspicuously Young,” an examination of television’s effect on a new generation of writers.

Wallace’s previous collections often included expanded articles with extra material cut from previously published pieces (like the cruise ship one and the state fair one). It would be wonderful to read a longer version of his NY Times piece on Federer but for obvious reasons I’m not holding my breath. Even just the first paragraph makes me want to sit down and read the whole thing for like a fifth time:

Almost anyone who loves tennis and follows the men’s tour on television has, over the last few years, had what might be termed Federer Moments. These are times, as you watch the young Swiss play, when the jaw drops and eyes protrude and sounds are made that bring spouses in from other rooms to see if you’re O.K.

On the eve of the release of her first novel specifically written for adult readers, Ian Parker profiles J.K. Rowling for the New Yorker. In many ways, this passage about Harry Potter sums up Parker’s take on Rowling herself:

For all the satisfying closure provided by “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows,” gloomier readers may still detect a note of melancholy; there is a narrowness of life for former Hogwarts students, whose career opportunities barely extend beyond the wizard civil service, wizard schoolteaching, and professional Quidditch. This magical society has no use for science; there’s little commerce; and thousands of years of wizarding seems to have generated no culture beyond a short volume of fables and a tabloid newspaper. (Wizard technology is often a cutely flawed approximation of non-wizard technology — owls for e-mail — and one wonders how quickly Harry and his schoolfriends could have won their battles against the evil Lord Voldemort, given two or three cell phones and a gun.) In a time of wizard peace, at least, Harry’s separation from the real world — even as he lives in it — can seem tragic.

In a time of personal prosperity, Rowling’s separation from the real world — even as she lives in it — can seem tragic.

From Steven Johnson comes Future Perfect, a new book about “progress in a networked age”.

Combining the deft social analysis of Where Good Ideas Come From with the optimistic arguments of Everything Bad Is Good For You, New York Times bestselling author Steven Johnson’s Future Perfect makes the case that a new model of political change is on the rise, transforming everything from local governments to classrooms, from protest movements to health care. Johnson paints a compelling portrait of this new political worldview — influenced by the success and interconnectedness of the Internet, but not dependent on high-tech solutions — that breaks with the conventional categories of liberal or conservative thinking.

With his acclaimed gift for multi-disciplinary storytelling and big ideas, Johnson explores this new vision of progress through a series of fascinating narratives: from the “miracle on the Hudson” to the planning of the French railway system; from the battle against malnutrition in Vietnam to a mysterious outbreak of strange smells in downtown Manhattan; from underground music video artists to the invention of the Internet itself.

At a time when the conventional wisdom holds that the political system is hopelessly gridlocked with old ideas, Future Perfect makes the timely and inspiring case that progress is still possible, and that new solutions are on the rise. This is a hopeful, affirmative outlook for the future, from one of the most brilliant and inspiring visionaries of contemporary culture.

This is contrary to what we’ve been hearing from The Shallows et al.

In the New Yorker, Salman Rushdie describes how quickly his entire life changed after Iran’s Ruhollah Khomeini issued a fatwa calling for Rushdie’s “execution”.

He unlocked the front door, went outside, got into the car, and was driven away. Although he did not know it then — so the moment of leaving his home did not feel unusually freighted with meaning — he would not return to that house, at 41 St. Peter’s Street, which had been his home for half a decade, until three years later, by which time it would no longer be his.

The article is excerpted from Rushdie’s memoir, Joseph Anton, which comes out next week. Joseph Anton was the name Rushdie adopted in hiding and, now that I think about it, explains why the NYer piece was written in the third person.

Newer posts

Older posts

Stay Connected