kottke.org posts about medicine

In 1961, surgeon Leonid Rogozov was the only physician stationed on an isolated 12-man Soviet base in Antarctica when he developed appendicitis. He had to remove his appendix himself.

“I didn’t permit myself to think about anything other than the task at hand. It was necessary to steel myself, steel myself firmly and grit my teeth. In the event that I lost consciousness, I’d given Sasha Artemev a syringe and shown him how to give me an injection. I chose a position half sitting. I explained to Zinovy Teplinsky how to hold the mirror. My poor assistants! At the last minute I looked over at them: they stood there in their surgical whites, whiter than white themselves. I was scared too. But when I picked up the needle with the novocaine and gave myself the first injection, somehow I automatically switched into operating mode, and from that point on I didn’t notice anything else.

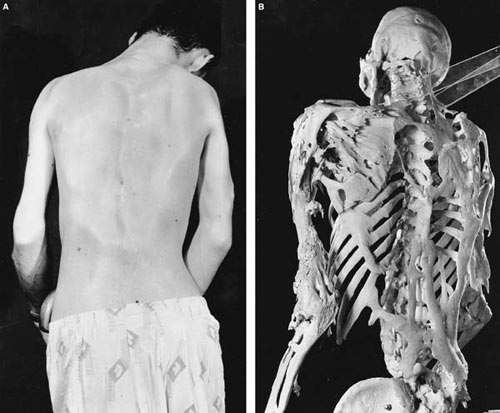

Anticipating cries of “photos or it didn’t happen”, his assistants documented the scene: here’s Rogozov operating on himself (and another).

The eggs for the swine flu vaccine are produced by dozens of farms classified by the US government as part of our country’s “critical infrastructure”.

To ensure it had enough eggs to meet pandemic-level demand, the government invested more than $44 million in the program over five years; more than 35 farms are now involved in this feathered Manhattan Project. No signs advertise the farms’ involvement in the program, and visits from the outside world are discouraged. The government won’t disclose where the farms are located, and the farmers are told to keep quiet about their work — not even the neighbors are to know.

These don’t exactly sound like free-range operations:

After nine months of service, [the chickens] are typically euthanized because they can no longer lay “optimal eggs,” Mr. Robinson said. “They’ve served their government,” he said.

(thx, micah)

Whoa, I had no idea that giving birth at home without a doctor or midwife was a thing that people were doing now.

After giving birth to her first baby in the hospital, Schoenborn, 31, chose to have her next four children at home — by herself. Although her husband was in the house during the births, he didn’t help with the deliveries.

“My hospital births were very managed,” says Schoenborn. “I wanted privacy and to be free of internal exams. I wanted to give birth in an upright position and they want you to lie down. I feel birth is an instinctive process and in the hospital they treat women like they’re broken and birth like an illness.”

The most striking feature of the H1N1 flu vaccine manufacturing process is the 1,200,000,000 chicken eggs required to make the 3 billion doses of vaccine that may be required worldwide. There are entire chicken farms in the US and around the world dedicated to producing eggs for the purpose of incubating influenza viruses for use in vaccines. No wonder it takes six months from start to finish. But we’ll get to that in a minute.

The most commonly used process for manufacturing an influenza vaccine was developed in the 1940s — one of its co-inventors was Jonas Salk, who would go on to develop the polio vaccine — and has remained basically unchanged since then. The process is coordinated by the World Health Organization and begins with the detection of a new virus (or rather one that differs significantly from those already going around); in this instance, the Pandemic H1N1/09 virus. Once the pandemic strain has been identified and isolated, it is mixed with a standard laboratory virus through a technique called genetic reassortment, the purpose of which is to create a hybrid virus (also called the “reference virus strain”) with the pandemic strain’s surface antigens and the lab strain’s core components (which allows the virus to grow really well in chicken eggs). Then the hybrid is tested to make sure that it grows well, is safe, and produces the proper antigen response. This takes about six to nine weeks.

[Quick definitional pause. Antigen: “An antigen is any substance that causes your immune system to produce antibodies against it. An antigen may be a foreign substance from the environment such as chemicals, bacteria, viruses, or pollen. An antigen may also be formed within the body, as with bacterial toxins or tissue cells.” So, when the H1N1 vaccine gets inside your body, the pandemic strain’s surface antigens will produce antibodies against it.]

At roughly the same time, a parallel effort to produce what are referred to as reference reagents is undertaken. The deliverable here is a standardized kit provided to vaccine manufacturers so that they can test how much virus they are making and how effective it is. This process serves to standardize vaccine doses across manufacturers and takes four months to complete. WHO notes that this part of the process is “often a bottleneck to the overall timeline for manufacturers to generate the vaccine”.

Once the reference virus strain is produced, it is sent to pharmaceutical companies (Novartis, Sanofi Pasteur, etc.) for large-scale production of the vaccine. The companies fine-tune the virus to increase yields and produce seed virus banks that will be used in the bulk production.

And this is where the 1.2 billion chicken eggs come in. A portion of the seed virus is injected into each 9- to 12-day old fertilized egg. The virus incubates in the egg white for two to three days and is then separated from the egg.

For the shot vaccine, the virus is sterilized so that it won’t make anyone sick. This is the magic part of the vaccine: it’s got the pandemic virus antigens that make your body produce the antibodies to fight the virus but the virus is inactive so it won’t make you ill. For the nasal spray vaccine, the virus is left alive and attenuated to survive only in the nose and not the warmer lungs; it’ll infect you enough to produce antibodies but not enough to make you sick. Either way, the surface antigens are separated out and purified to produce the active ingredient in the vaccine. Each batch of antigen takes about two weeks to produce. With enough laboratory space and chicken eggs, the companies can crank out an infinite amount of purified antigens, but those resources are limited in practice.

[Side note. You may have noticed that the H1N1 vaccine has been difficult to find in some places around the US. The vaccine manufacturers have said that the Pandemic H1N1/09 virus when combined with the standard laboratory virus does not grow as fast in the eggs as they anticipated. The batches of antigens from each egg have been smaller than expected, up to five or even ten times smaller in some cases. Hence the slow rollout of the vaccine.]

The purified antigen is then tested against the aforementioned reference reagents once they are ready. The antigen is diluted to the required concentration and placed into properly labelled vials or syringes. Further testing is performed to make sure the vaccine won’t make anyone ill, to confirm the correct concentration, and for general safety. At this point clinical testing in humans is required in western Europe but not in the United States. Finally, each company’s vaccine has to be approved by the appropriate regulatory body in each country — that’s the FDA in the case of the US — and then the vaccine is distributed to medical facilities around the country.

Sources and more information: WHO, WHO, WHO, WHO, CDC, Time, Washington Post, The Big Picture, Influenza Report, NPR, Wikipedia, Wikipedia, Wikipedia, Wikipedia.

Update: Included in a recent 60 Minutes segment on the H1N1 vaccine is a look at the manufacturing process. (thx, @briandigital)

The process of inoculation against diseases like smallpox has been known for at least 1200 years. An 8th-century Indian book contains a how-to chapter on smallpox inoculations. Chinese use of the technique dates back to the first millennium as well. The technique was imported to Europe via the Ottoman Empire in 1721 and reached America at about the same time.

The practice is documented in America as early as 1721, when Zabdiel Boylston, at the urging of Cotton Mather, successfully inoculated two slaves and his own son. Mather, a prominent Boston minister, had heard a description of the African practice of inoculation from his Sudanese slave, Onesimus, in 1706, but had been previously unable to convince local physicians to attempt the procedure. Following this initial success, Boylston began performing inoculations throughout Boston, despite much controversy and at least one attempt upon his life. The effectiveness of the procedure was proven when, of the nearly three hundred people Boylston inoculated during the outbreak, only six died, whereas the mortality rate among those who contracted the disease naturally was one in six.

In a criticism of inoculation that would not seem so out of place regarding vaccination today, Voltaire takes his countrymen to task for not inoculating their children.

It is inadvertently affirmed in the Christian countries of Europe that the English are fools and madmen. Fools, because they give their children the small-pox to prevent their catching it; and madmen, because they wantonly communicate a certain and dreadful distemper to their children, merely to prevent an uncertain evil. The English, on the other side, call the rest of the Europeans cowardly and unnatural. Cowardly, because they are afraid of putting their children to a little pain; unnatural, because they expose them to die one time or other of the small-pox. But that the reader may be able to judge whether the English or those who differ from them in opinion are in the right, here follows the history of the famed innoculation, which is mentioned with so much dread in France.

Wired has a long piece by Amy Wallace about the anti-science anti-vaccine crowd.

Ah, risk. It is the idea that fuels the anti-vaccine movement — that parents should be allowed to opt out, because it is their right to evaluate risk for their own children. It is also the idea that underlies the CDC’s vaccination schedule — that the risk to public health is too great to allow individuals, one by one, to make decisions that will impact their communities. (The concept of herd immunity is key here: It holds that, in diseases passed from person to person, it is more difficult to maintain a chain of infection when large numbers of a population are immune.)

Update: I am on Team Tom Scocca on this issue:

Anti-vaccine activists are degenerate idiots who deserve to get polio and live out their days in iron lungs while Child Protective Services takes away their children to be properly raised. Or tetanus. Get lockjaw and shut up and die. What’s the point of living in 21st-century America if not to avoid dying of stupid, easily preventable disease?

And Slate has an article about the effects of unvaccinated children on those with weak immune systems.

Ordinarily I wouldn’t question others’ parenting choices. But the problem is literally one of live or don’t live. While that parent chose not to vaccinate her child for what she likely considers well-founded reasons, she is putting other children at risk. In this instance, the child at risk was my son. He has leukemia.

(thx, cedar)

Update: Ben Goldacre on anti-vaccine scares as a cultural thing, not a science thing:

There’s something very interesting about vaccine scares. These are cultural products. They’re not about evidence. If vaccine scares were about genuine scientific evidence showing that a vaccine caused a disease, then the vaccine scares would happen all around the world at exactly the same time, because information can disseminate itself around the world very rapidly these days. But what you find is that vaccine scares actually respect cultural and national boundaries.

(via lined and unlined)

Should you vaccinate your kids against the swine flu this winter? Will it even work against the H1N1 virus? Or will it even be available? Maybe we should be focused on a much simplier solution: keeping our hands clean.

Using soap and water or a sanitizer virtually eliminated the presence of the [H1N1] virus [in an Australian study].

Update: I’ve gotten a few emails so a clarification: vaccines are obviously not bad. Vaccinate your kids against the H1N1 virus when a vaccine becomes available if you feel that’s the right thing to do. It’s just that in the United States people often emphasize the quick fix over something that can be effective but requires a change in behavior. Much of what you hear about the damn swine flu is people being infected, the deaths, the coming vaccine, and how to protect our precious children from THE KILLER VIRUS THAT KILLS PEOPLE SO LET’S PANIC!! I thought it was important to call out something common sensical, unsexy, and effective like hand washing.

Update: I give up. Don’t wash your hands. It is completely ineffective and has never saved anyone from anything. Get vaccinated and stay inside. When you do go outside, wear a surgical mask and try not to go near other people.

Harvard Magazine has a nice profile of surgeon and writer Atul Gawande that talks about, among other things, his constant state of flow.

Gawande had seen that part of the man’s colon was ischemic — dead and gangrenous — and had ceased to move waste out of the body. He wasn’t sure about the cause, but suspected a blood clot. One thing was clear: without immediate surgery, the colon would rupture.

After examining the patient, Gawande conferred with the resident in the corridor outside the man’s room. He went through a familiar and well-practiced set of actions that he seemed to do without thinking: slipping his ring finger into his mouth to moisten it, working his wedding band off, unbuckling his watchband, threading it through the ring, and refastening it, all the while carrying on a conversation about stopping the patient’s anti-clotting medication and getting a vascular surgeon to assist.

Scientists are gradually coming to the conclusion that exposure to organophosphate pesticides increases the risk of Parkinson’s disease.

Taken together, 30-plus years of research add up to an increasingly persuasive conclusion: exposure to pesticides and other toxins increases the risk of Parkinson’s disease, and we are only now beginning to wrestle with the true scope of the damage.

(thx, peter)

At six, Hannah Clark received a heart transplant…but they kept the second heart in her chest as well. Ten years later, her new heart failed and they were able to remove it because her old heart had mended itself in the meantime.

For the first few months, the new heart did nearly all the work, but this “rest” gave Hannah’s own heart a chance to begin recovery. By the time of the second heart was finally removed, Hannah’s heart was doing virtually all the work itself.

It’s amazing what doctors can entice the human body to do.

I’ve got two follow-ups to share with you regarding Atul Gawande’s New Yorker piece about healthcare costs in the US (kottke.org post). In the Wall Street Journal, Abraham Verghese argues that in order for a healthcare reform plan to be successful, it has to include cost cutting.

I recently came on a phrase in an article in the journal “Annals of Internal Medicine” about an axiom of medical economics: a dollar spent on medical care is a dollar of income for someone. I have been reciting this as a mantra ever since. It may be the single most important fact about health care in America that you or I need to know. It means that all of us — doctors, hospitals, pharmacists, drug companies, nurses, home health agencies, and so many others — are drinking at the same trough which happens to hold $2.1 trillion, or 16% of our GDP. Every group who feeds at this trough has its lobbyists and has made contributions to Congressional campaigns to try to keep their spot and their share of the grub. Why not? — it’s hog heaven. But reform cannot happen without cutting costs, without turning people away from the trough and having them eat less. If you do that, you have to be prepared for the buzz saw of protest that dissuaded Roosevelt, defeated Truman’s plan and scuttled Hillary Clinton’s proposal.

In Gawande’s example, what Verghese is saying is that you can’t just make McAllen’s healthcare system adopt an El Paso type of system without a whole lot of pain.

Gawande addressed some of the criticisms of his article on the New Yorker site. One of the major criticisms was that McAllen’s higher costs were associated with higher levels of poverty and unhealthiness:

As I noted in the piece, McAllen is indeed in the poorest county in the country, with a relatively unhealthy population and the problems of being a border city. They have a very low physician supply. The struggles the people and medical community face there are huge. But they are just as huge in El Paso — its residents are barely less poor or unhealthy or under-supplied with physicians than McAllen, and certainly not enough so to account for the enormous cost differences. The population in McAllen also has more hospital beds than four out of five American cities.

On Friday, Atul Gawande gave the commencement address at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine. The address touched on some of the same themes as his recent piece on the differing costs of healthcare across the US. He began with an anecdote about how observation of well-nourished children in poor Vietnamese villages led to village-wide improvments in curbing malnutrition.

The villagers discovered that there were well-nourished children among them, despite the poverty, and that those children’s mothers were breaking with the locally accepted wisdom in all sorts of ways — feeding their children even when they had diarrhea; giving them several small feedings each day rather than one or two big ones; adding sweet-potato greens to the children’s rice despite its being considered a low-class food. The ideas spread and took hold. The program measured the results and posted them in the villages for all to see. In two years, malnutrition dropped sixty-five to eighty-five per cent in every village the Sternins had been to.

And I don’t know why, but I’ve always thought of surgery as primarily a cerebral pursuit; a great surgeon is so because he’s clever and smart. A short passage from Gawande’s address reveals that perhaps that’s not the case:

In surgery, for instance, I know that I have more I can learn in mastering the operations I do. So what does a surgeon like me do? We look to those who are unusually successful — the positive deviants. We watch them operate and learn their tricks, the moves they make that we can take home.

So surgeons learn surgery in the same way that kids learn Kobe Bryant’s post moves from SportsCenter highlights?

From the Effects Measure blog:

Influenza is a virus full of mystery and surprises. The more we study it the more complicated it becomes. Remember the adage: “If you’ve seen one flu pandemic, you’ve seen one flu pandemic.”

This reminds me of the first line of Anna Karenina:

Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

(via david archer)

Bone is a springy and salty wonder that is proving much more functional within the human body than originally thought.

The skeleton is a multipurpose organ, offering a ready source of calcium for an array of biochemical tasks, and housing the marrow where blood cells are born. Yet above all the skeleton allows us to locomote, which means it gets banged up and kicked around. Paradoxically, it copes with the abuse and resists breaking apart in a major way by microcracking constantly. “Bone microcracks, that’s what it does,” Dr. Ritchie said. “That’s how stresses are relieved.” […] But like all forms of health care, bone repair doesn’t come cheap, and maintaining skeletal integrity consumes maybe 40 percent of our average caloric budget.

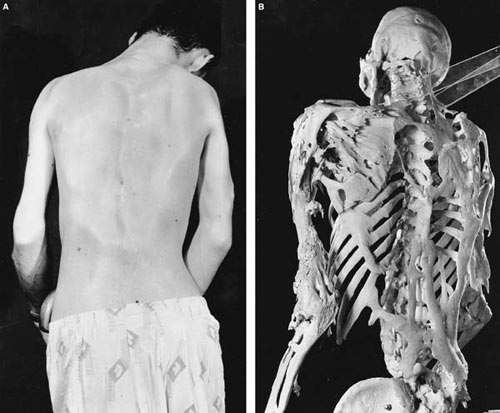

The article leads off with the story of Harry Eastlack, whose body repaired itself with bone-building cells no matter what the injury, essentially giving him a not-so-Wolverine-like second skeleton. Here’s a photo I found of Eastlack’s skeleton, which is housed at the Mutter Museum of the College of Physicians.

Since I don’t use Adderall or Provigil, it took me a few days to get through this New Yorker article about neuroenhancing drugs. The main takeaway? Like cosmetic body modification in the 80s, mind modification through prescription chemical means is already commonplace for some and will soon be for many.

Chatterjee worries about cosmetic neurology, but he thinks that it will eventually become as acceptable as cosmetic surgery has; in fact, with neuroenhancement it’s harder to argue that it’s frivolous. As he notes in a 2007 paper, “Many sectors of society have winner-take-all conditions in which small advantages produce disproportionate rewards.” At school and at work, the usefulness of being “smarter,” needing less sleep, and learning more quickly are all “abundantly clear.” In the near future, he predicts, some neurologists will refashion themselves as “quality-of-life consultants,” whose role will be “to provide information while abrogating final responsibility for these decisions to patients.” The demand is certainly there: from an aging population that won’t put up with memory loss; from overwrought parents bent on giving their children every possible edge; from anxious employees in an efficiency-obsessed, BlackBerry-equipped office culture, where work never really ends.

The article is full of wonderful vocabulary. Like the “worried well”: those people who are healthy but go to the doctor anyway to see if they can be made more healthy somehow. Being concerned about how good you’ve got it and attempting to do something about it seems to be another one of those uniquely American phenomena caused by an overabundance of free time & disposable income and the desire to overachieve. See also the impoverished wealthy, the dumb educated, and fat fit.

Karrie Karahalios created a program that interprets conversations and generates real-time visual feedback. A social mirror of sorts.

The “clock” shows the progress of the talk. Three times a second, a color bar pops up showing who was speaking. The louder the speech, the longer the bar. Interruptions are shown as overlapping color bars. Every minute, a new circle of bars is rendered in a visual record akin to the rings of tree trunk.

Referred to as a “conversation clock,” it’s already been tested with kids with low-functioning autism, teaching them to vocalize. One speech specialist thinks it can help kids with Asperger’s, who tend to dominate conversations, learn not to “monologue” so much.

Marriage counselors are also using it to teach your husband how to shut up for five minutes.

Eno is an antacid produced by GlaxoSmithKline. It’s globally distributed, mainly across South America, India, and the Middle East, and it’s available as sachets and tablets in both Lemon and an ambiguous “Regular” flavor.

Ogilvy & Mather produced a stunning print advertisement for the company, featuring a gun made of food. Quite an improvement over Eno’s commercial from the 80s, although if the packets made me seem as effervescent as the actor, perhaps I’d take some on my down days.

via Coloribus

Studies indicate that kids who are exposed to bacteria, viruses, worms, and dirt have healthier immune systems.

He said that public health measures like cleaning up contaminated water and food have saved the lives of countless children, but they “also eliminated exposure to many organisms that are probably good for us.” “Children raised in an ultraclean environment,” he added, “are not being exposed to organisms that help them develop appropriate immune regulatory circuits.”

One of the decisions we made even before Ollie was born was that he was going to be a dirty kid. We wash our hands often with non-antibacterial soap and water, especially after being on the subway, but otherwise don’t worry about it much. I can count on one hand how many times I’ve used the antibacterial hand sanitizer that seemingly comes bundled with toddlers these days.

Update: See also The Germ-Phobic Mommies.

Google is tracking search terms to predict when the flu is going to hit different areas in the US.

During the 2007-2008 flu season, an early version of Google Flu Trends was used to share results each week with the Epidemiology and Prevention Branch of the Influenza Division at CDC. Across each of the nine surveillance regions of the United States, we were able to accurately estimate current flu levels one to two weeks faster than published CDC reports.

The 103 beats/minute of the Bee Gees’ Stayin’ Alive is the perfect beat for performing chest compressions during CPR.

In a small but intriguing study from the University of Illinois medical school, doctors and students maintained close to the ideal number of chest compressions doing CPR while listening to the catchy, sung-in-falsetto tune from the 1977 movie “Saturday Night Fever.”

(via clusterflock)

Due to a hand tremor, musician Eddie Adcock was having trouble playing the banjo. During the surgery to fix the problem, the doctors had Adcock play his banjo to isolate the problem in his brain and then they made the repair. Video here. (via delicious ghost)

Ten people who have unusual medical conditions, including the woman who can’t stop orgasming, the woman who is allergic to cell phones and microwaves, and the boy who can’t sleep.

I try not to miss any of Atul Gawande’s New Yorker articles, but his piece on itching from this week’s issue is possibly the most interesting thing I’ve read in the magazine in a long time. He begins by focusing on a specific patient for whom compulsive itching has become a very serious problem. (Warning, this quote is pretty disturbing…but don’t let it deter you from reading the article.)

…the itching was so torturous, and the area so numb, that her scratching began to go through the skin. At a later office visit, her doctor found a silver-dollar-size patch of scalp where skin had been replaced by scab. M. tried bandaging her head, wearing caps to bed. But her fingernails would always find a way to her flesh, especially while she slept.

One morning, after she was awakened by her bedside alarm, she sat up and, she recalled, “this fluid came down my face, this greenish liquid.” She pressed a square of gauze to her head and went to see her doctor again. M. showed the doctor the fluid on the dressing. The doctor looked closely at the wound. She shined a light on it and in M.’s eyes. Then she walked out of the room and called an ambulance. Only in the Emergency Department at Massachusetts General Hospital, after the doctors started swarming, and one told her she needed surgery now, did M. learn what had happened. She had scratched through her skull during the night — and all the way into her brain.

From there, Gawande pulls out to tell us about itching/scratching (the two are inseparable), then about a recent theory of how our brains perceive the world (“visual perception is more than ninety per cent memory and less than ten per cent sensory nerve signals”), and finally about a fascinating therapy initially developed for those who experience phantom limb pain called mirror treatment.

Among them is an experiment that Ramachandran performed with volunteers who had phantom pain in an amputated arm. They put their surviving arm through a hole in the side of a box with a mirror inside, so that, peering through the open top, they would see their arm and its mirror image, as if they had two arms. Ramachandran then asked them to move both their intact arm and, in their mind, their phantom arm-to pretend that they were conducting an orchestra, say. The patients had the sense that they had two arms again. Even though they knew it was an illusion, it provided immediate relief. People who for years had been unable to unclench their phantom fist suddenly felt their hand open; phantom arms in painfully contorted positions could relax. With daily use of the mirror box over weeks, patients sensed their phantom limbs actually shrink into their stumps and, in several instances, completely vanish. Researchers at Walter Reed Army Medical Center recently published the results of a randomized trial of mirror therapy for soldiers with phantom-limb pain, showing dramatic success.

Crazy! Gawande documents and speculates about other applications of this treatment, including using virtual reality representations instead of mirrors and utilizing multiple mirrors for treatment of M.’s itchy scalp. Anyway, read the whole thing…highly recommended.

Surprisingly, the Jumping Frenchmen of Maine Disorder is a real, no-fooling psychological behavior. Here’s an abstract from Neurology magazine briefly describing it:

The “Jumping Frenchmen of Maine” were described by George Beard in 1878. They had an excessive startle response, sometimes with echolalia, echopraxia, or forced obedience. In 1885, Gilles de la Tourette concluded that “jumping” was similar to the syndrome that now bears his name. Direct observations of jumpers have been scarce. We studied eight jumpers from the Because region of Quebec. In our opinion, this phenomenon is not a neurologic disease, but can be explained in psychological terms as operant conditioned behavior. Our cases were related to specific conditions in lumber camps in the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century.

(thx, nathan)

Doctors and researchers are investigating the source of a new disease caused by aerosolized pig brains.

Their working hypothesis is that the harvesting technique — known as “blowing brains” on the floor — produces aerosols of brain matter. Once inhaled, the material prompts the immune system to produce antibodies that attack the pig brain compounds, but apparently also attack the body’s own nerve tissue because it is so similar.

(via frontal cortex)

Dr. Jay Parkinson M.D. emailed in to tell me about his new medical practice in Williamsburg. He’s got no office (housecalls only), takes appointment requests via SMS, email, or IM, handles some follow-ups over video chat, and specializes in the 18-40 age group without traditional health insurance. The goal, states Parkinson, is to “mix the service of an old-time, small town doctor with the latest technology to keep you and your bank account healthy”.

To give you an idea of how the practice operates, here’s a recap of his first day on the job:

Yesterday went quite well and I was very happy with the amount of money I kept out of the hands of companies that attempt to take advantage of how difficult it is to find prices for medications and healthcare services. For example, the first patient I saw needed a medication that Walgreens offered for $60. I called my tried and true Williamsburg mom-and-pop pharmacy only a few blocks from Walgreens and talked to Arthur the Pharmacist who said he sells it for $15. “Thanks Arthur.” “No thank you Jay.” The way it should be done.

My second patient was getting a certain medication for years every month by mail from Walgreens that costs $63 per month. I knew where she could get the same medication for $42 a month. I just saved her $252 per year. After she made her $200 down payment on my services via PayPal, her monthly fee for my services is now only $17 a month. But I just saved her $21 a month on her monthly mail order medication. She’s essentially getting the rest of the year of my services for free. Not bad.

Sounds fantastic. If only every doctor was this much of an advocate for his patients.

P.S. Parkinson also happens to be a heck of a photographer (@ Flickr). Some photos NSFW. I linked to this interview about his photography between him and Joerg Colberg last May.

Update: The WSJ Health blog has a short interview with Parkinson, followed by a lengthy comment thread.

Oscar the cat lives at the Steere House Nursing and Rehabilitation Center in Providence, Rhode Island. According to an article in the New England Journal of Medicine, Oscar possesses a peculiar talent…he knows when the residents there are going to die and curls up with them for comfort before they pass.

Making his way back up the hallway, Oscar arrives at Room 313. The door is open, and he proceeds inside. Mrs. K. is resting peacefully in her bed, her breathing steady but shallow. She is surrounded by photographs of her grandchildren and one from her wedding day. Despite these keepsakes, she is alone. Oscar jumps onto her bed and again sniffs the air. He pauses to consider the situation, and then turns around twice before curling up beside Mrs. K.

One hour passes. Oscar waits. A nurse walks into the room to check on her patient. She pauses to note Oscar’s presence. Concerned, she hurriedly leaves the room and returns to her desk. She grabs Mrs. K.’s chart off the medical-records rack and begins to make phone calls.

Within a half hour the family starts to arrive. Chairs are brought into the room, where the relatives begin their vigil. The priest is called to deliver last rites. And still, Oscar has not budged, instead purring and gently nuzzling Mrs. K. A young grandson asks his mother, “What is the cat doing here?” The mother, fighting back tears, tells him, “He is here to help Grandma get to heaven.” Thirty minutes later, Mrs. K. takes her last earthly breath. With this, Oscar sits up, looks around, then departs the room so quietly that the grieving family barely notices.

For some, the hospital is a place to go to get sick, not to get healthy. At the Veterans Affairs hospital in Pittsburgh, they’re cutting down on diseases passing from patient to patient by testing arriving patients for drug-resistant bacteria, more careful use of equipment, and careful isolation of the most sick. A surgical unit in the hospital has cut their infection rate by 78% since 2001.

A company called Lifeforce has received FDA approval to store white blood cells for people as a “back-up copy of your immune system”. The idea is that those pre-diseased cells could be reproduced in the lab and infused back into your body when needed to fight off infection or deal with the aftermath of chemotherapy.

How doctors make their decisions is being studied in the hopes of making medical care better. “Doctors can also make mistakes when their judgments about a patient are unconsciously influenced by the symptoms and illnesses of patients they have just seen. Many common infections tend to occur in epidemics, afflicting large numbers of people in a single community at the same time; after a doctor sees six patients with, say, the flu, it is common to assume that the seventh patient who complains of similar symptoms is suffering from the same disease.”

Newer posts

Older posts

Stay Connected