Translating Homer in public

I can’t claim to have finished Emily Wilson’s translation of The Odyssey by Homer — epic poems are, well, epic — but I’m a huge fan of everything I’ve read, and especially Wilson’s Twitter feed, which is often devoted to explicating some small bit of Homeric text and comparing her approach to that of other translators.

Here, for example, she takes on the depiction of the Sirens. I’m going to pick and choose a few tweets, but you should read as much of the thread as you can.

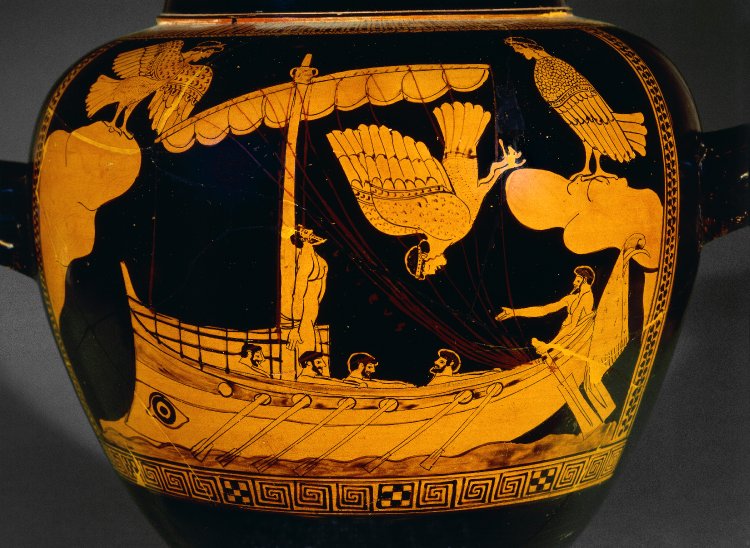

Everyone knows the story of the Sirens from the Odyssey. They’re the singers who tempt all those who sail past to listen to them forever, forgetful of their families. Odysseus, instructed by Circe, has himself bound to the mast so he can listen to their song.

— Emily Wilson (@EmilyRCWilson) March 4, 2018

But the Homeric Sirens passage, in Book 12, is surprising in at least two ways. One is how short it is; the episode has become a much bigger part of the Odyssey in modern retellings than it is in the Homeric poem.

— Emily Wilson (@EmilyRCWilson) March 4, 2018

Secondly, the Sirens in Homer aren’t sexy. e.g. we learn nothing even about their hair — in contrast to other divine temptresses. The seduction they offer is cognitive: they claim to know everything about the war in Troy, and everything on earth. They tell the names of pain.

— Emily Wilson (@EmilyRCWilson) March 4, 2018

This last observation prompted a haunting distillation by Lev Mirov of Odysseus’s journey and his encounter with the Sirens:

This whole thread is amazing but, I think of this:

— Lev Mirov (@thelionmachine) March 5, 2018

the forbidden knowledge Odysseus cannot pass up?

Essentially:

tell me the name

of the hole in my heart

tell me what

this war meant

and what is wrong with me.

(nothing, nothing, nothing, the name of pain is sung.) https://t.co/LlFFxOqVaX

Back to Wilson, who translates the brutally short passage of the sirens this way:

Wilson:

— Emily Wilson (@EmilyRCWilson) March 4, 2018

“Now stop your ship and listen to our voices.

All those who pass this way hear honeyed song

poured from our mouths. The music brings them joy,

and they go on their way with greater knowledge”.

I don’t change my regular iambic pentameter.

She explains:

I wanted the Sirens to sound seductive, but in aural and cognitive ways. I tried to echo some of the alliterating sibilants in the original — a bit like Kaa in Jungle Book, “Trust in Me”. NB: it’s the mouth, not the lips, that matters in most of Odysseus’ troubles at sea.

— Emily Wilson (@EmilyRCWilson) March 4, 2018

Mouths (of giants, whirlpools, cyclopses and men) keep eating the wrong things, and mouths (of goddesses, men, witches, singers and shades) speak and sing to enable or thwart the onward journey. Not lips, which can be pretty and kissable. Mouths are powerful and dangerous.

— Emily Wilson (@EmilyRCWilson) March 4, 2018

Translation is hard, but translation in public is harder and better. There’s a richness in the commentary, and also a reckoning with the accretion of meanings that have come down through past readings, that you don’t often get without diving into scholarly apparatus. It’s not just peeling back the plaster; it’s trying to understand the work that plaster did in holding the whole structure together. Just remarkable.

Update: Dan Chiasson wrote about Wilson’s use of Twitter for the New Yorker.

Stay Connected