Emily Wilson’s eagerly-awaited translation of Homer’s Iliad will be out on September 26 and is finally available for pre-order! I loved her version of The Odyssey (I read it to my kids and we all got a lot out of it).

Wilson posts a lot about her process on Twitter but hasn’t said too much about the finished book yet, aside from this tweet back in February:

It feels bittersweet to be at the end of my eleven-year labor of love, creating verse translations of the Homeric epics. I’m working through Iliad proofs, and full of gratitude that I have had this magical opportunity, to work so closely for so long with these sublime poems.

I’m excited to read the complete Homeric epic in the fall! In the meantime, you can pre-order it at Amazon or Bookshop.org.

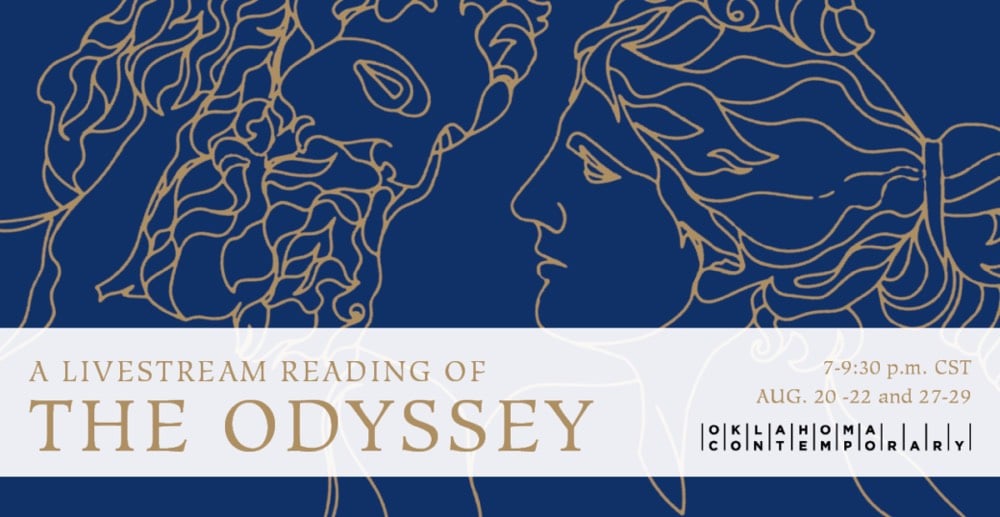

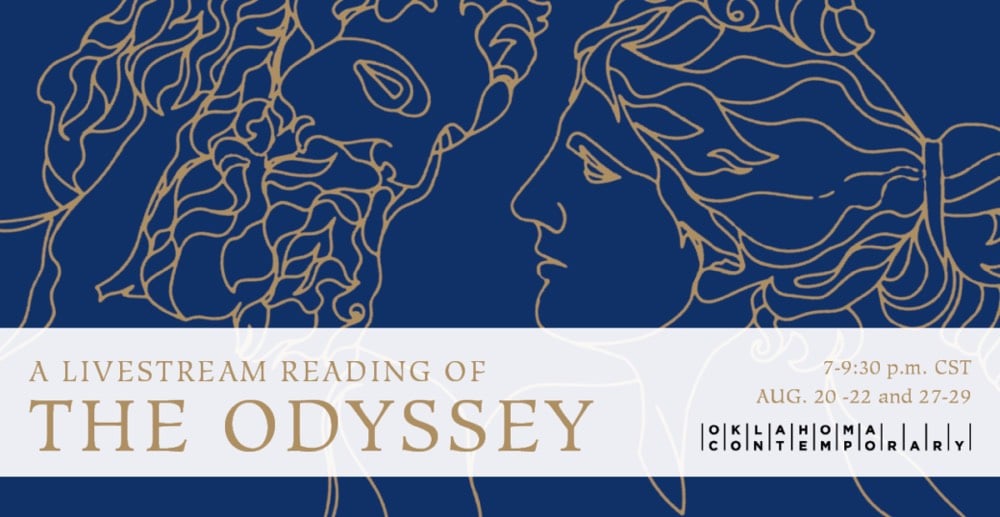

On two consecutive weekends in late August (Aug 20-22 & Aug 27-29), the Oklahoma Contemporary museum will be livestreaming a reading of Emily Wilson’s excellent translation of The Odyssey. Wilson herself will be joined in reading the entire book by folks like actress Bebe Neuwirth, singer-songwriter Leslie Feist, writer Rebecca Nagle (who I’ve been listening to on the fascinating and infuriating This Land podcast), Oklahoma City mayor David Holt, and several other folks.

The exact schedule is TBD, but the event will be streamed on YouTube and Facebook. Check back here for details closer to the date. (thx, sarah)

Emily Wilson, whose translation of The Odyssey recently reintroduced the epic to a wider non-classics audience, has now cheekily translated the tale of Odysseus into a series of limericks. She starts off:

There was a young man called Telemachus

who was bullied and in a dilemma ‘cause

he missed his lost dad

and his mom made him mad

and he almost got killed by Eurymachus.

And here’s the bit about Odysseus’ men eating the cattle of Helios, which earns them a thunderbolt from Zeus.

The men were fed up with their boss,

the rich guy, who’d gone for a doss.

They ate up the cattle,

which shortly proved fatal,

and all of their short lives were lost.

So good.

Emily Wilson, who produced this banging translation of The Odyssey and is currently at work on The Iliad, recently tweeted a list of “reasons why it’s more or less impossible to translate Homer into English in a satisfactory way”. Here are a few of those reasons:

2. There aren’t enough onomatopoeic words for very loud chaotic noises.

3. “Many”, especially when repeated over and over, sounds childish; repeating “lots of” sounds worse. There are not enough words for large numbers of people or objects, and those we have (“multitude”, “plethora”, “myriad”) are often too pompous to use repeatedly.

6. Terms for social rank imply a particular wrong social order. “King” suggests monarchy. “Chief” has several connotations, none quite right. “General”, “Marshal”, “Officer” etc. suggest an established military hierarchy. “Mr” & “Sir” suggest business suits.

Last year, Wilson shared her process behind translating the first two lines of The Odyssey.

How much of Troy did he sack? ptoliethron is the lengthened form of polis, “city” (later, city-state). Sometimes =central part of city. But sacking just part of Troy isn’t really enough… Shd. the translator make it non-dumb if possible, or not worry about that?

There’s alliteration (polla/ plangthe … ptolietron epersen, notice the “p” sounds). What, if anything, should or can a translator do, when the sound of every word in her language is different from the words of the original? And, what to do about meter? Genre? Tone?

What’s the judgment, if any? Or narrative perspective? Do we feel OK about Odysseus being defined, instantly, as a city-sacker (ptoliporthos, one of his standard epithets)? Is the narrative voice invested in one side or another? It’s very hard to say. A judgment call.

And it goes on like that for more than a dozen tweets…for just two lines!

In this clip from the TV show Articulate (which airs on PBS), host Jim Cotter talks with Emily Wilson and Daniel Mendelsohn about The Odyssey, different versions of the self, translations, and more.

Emily Wilson: What is it to be in a family? What is it to be a person over time? For me, that’s one of the most fascinating questions just in general, but then The Odyssey speaks to that question of, am I the same person that I was 20 years ago? Am I the same person in America that I was in the UK? Is Ulysses the same person when he’s on the battlefield, verses when he’s with his son, verses when he’s with his wife? What is it to be the same or to be different? How do we treat people who are different from us? It’s a poem that’s about diaspora, immigration, emigration, travel, belonging, being at different places geographically and also being at different places spiritually and psychologically.

The kids and I have been reading Wilson’s translation of The Odyssey over the past several months together. I wasn’t quite sure if they’d like it or if they’d get bored, but they’ve been engaged the whole time and now that we’re nearing the end, everyone is eager to see how the story plays out and a little sad that it’s ending.

We probably won’t be reading Mendelsohn’s book next, but I might have to add An Odyssey: A Father, a Son, and an Epic to my reading stack:

When eighty-one-year-old Jay Mendelsohn decides to enroll in the undergraduate Odyssey seminar his son teaches at Bard College, the two find themselves on an adventure as profoundly emotional as it is intellectual. For Jay, a retired research scientist who sees the world through a mathematician’s unforgiving eyes, this return to the classroom is his “one last chance” to learn the great literature he’d neglected in his youth — and, even more, a final opportunity to more fully understand his son, a writer and classicist. But through the sometimes uncomfortable months that the two men explore Homer’s great work together — first in the classroom, where Jay persistently challenges his son’s interpretations, and then during a surprise-filled Mediterranean journey retracing Odysseus’s famous voyages — it becomes clear that Daniel has much to learn, too: Jay’s responses to both the text and the travels gradually uncover long-buried secrets that allow the son to understand his difficult father at last.

I’m currently reading Emily Wilson’s recent translation of The Odyssey, but until I looked at this map of Odysseus’ journey, I had little idea how scenic his route home was.1 The gods were hella pissed! All this time, I’d been imagining him pinballing around amongst the Greek islands in the Aegean Sea, but the gods and fates blew Odysseus and his men to all corners of the Mediterranean Sea: Italy, Africa, and even Ibiza in Spain. That dude was LOST. (via open culture)

I had been slowly making my way through Emily Wilson’s translation of The Odyssey, but on the advice of a Twitter pal, I backtracked and started reading it aloud to my kids. Which has been amazing…reading this story out loud really feels like we’re harkening back to the time of Homer.

One of the things we’re discussing as we go along are the repeated epithets…the descriptions of gods and people that are used over and over in the poem. Zeus is often not just Zeus — he is “the great Thunderlord Zeus” — and Dawn (the Greek goddess of the dawn) is almost never just Dawn, as Wilson explains in the introduction:

Dawn appears some twenty times in The Odyssey, and the poem repeats the same line, word for word, each time: emos d’erigeneia phane rhododaktulos eos: “But when early-born rosy-fingered Dawn appeared…” There is a vast array of such formulaic expressions in Homeric verse, which suggest that things have an eternal, infinitely repeatable presence. Different things will happen every day, but Dawn always appears, always with rosy fingers, always early.

Wilson combats this precise repetition, which can sound antiquated to modern ears, by varying the epithets according to the context:

The formulaic elements in Homer, especially the repeated epithets, pose a particular challenge. The epithets applied to Dawn, Athena, Hermes, Zeus, Penelope, Telemachus, Odysseus, and the suitors repeat over and over in the original. But in my version, I have chosen deliberately to interpret these epithets in several different ways, depending on the demands of the scene at hand. I do not want to deceive the unsuspecting reader about the nature of the original poem; rather, I hope to be truthful about my own text — its relationships with its readers and with the original. In an oral or semiliterate culture, repeated epithets give a listener an anchor in a quick-moving story. In a highly literate society such as our own, repetitions are likely to feel like moments to skip. They can be a mark of writerly laziness or unwillingness to acknowledge one’s own interpretative position, and can send a reader to sleep. I have used the opportunity offered by the repetitions to explore the multiple different connotations of each epithet.

The appearance of Dawn has already become a source of comic relief while we’re reading — “here she is again, with the roses!” — and I was curious to see Wilson’s differing interpretations, I gathered all the appearances of Dawn from the text:

The early Dawn was born; her fingers bloomed.

When newborn Dawn appeared with rosy fingers…

When rosy-fingered Dawn came bright and early…

Soon Dawn was born, her fingers bright with roses.

When Dawn appeared, her fingers bright with flowers…

When early Dawn appeared and touched the sky with blossom…

Then Dawn rose up from bed with Lord Tithonus, to bring the light to deathless gods and mortals.

When vernal Dawn first touched the sky with flowers…

But when the Dawn with dazzling braids brought day for the third time…

Then Dawn came from her lovely throne, and woke the girl.

Soon Dawn appeared and touched the sky with roses.

When bright-haired Dawn brought the third morning…

When early Dawn shone forth with rosy fingers…

But when the rosy hands of Dawn appeared…

Early the Dawn appeared, pink fingers blooming…

When early Dawn revealed her rose-red hands…

Then when rose-fingered Dawn came, bright and early…

On the third morning brought by braided Dawn…

Then the roses of Dawn’s fingers appeared again…

Dawn on her golden throne began to shine…

When Dawn came, born early, with her fingertips like petals…

The golden throne of Dawn was riding up the sky…

When rose-fingered Dawn appeared…

Then Dawn was born again; her fingers bloomed…

Then all at once Dawn on her golden throne lit up the sky…

…Dawn soon arrived upon her throne.

When newborn Dawn appeared with hands of flowers…

When early Dawn, the newborn child with rosy hands, appeared…

As she said this, the golden Dawn arrived.

…she roused the newborn Dawn from Ocean’s streams to bring the golden light to those on earth.

I think my favorite is probably “Soon Dawn was born, her fingers bright with roses” but I also appreciate the very first appearance in the text: “The early Dawn was born; her fingers bloomed”. Either way, what a great illustration of Wilson’s skill & the creative latitude involved in translation, along with a reminder for writers of the many different ways in which you can essentially say the same thing.

(The sunrise photo is from my Instagram.)

I can’t claim to have finished Emily Wilson’s translation of The Odyssey by Homer — epic poems are, well, epic — but I’m a huge fan of everything I’ve read, and especially Wilson’s Twitter feed, which is often devoted to explicating some small bit of Homeric text and comparing her approach to that of other translators.

Here, for example, she takes on the depiction of the Sirens. I’m going to pick and choose a few tweets, but you should read as much of the thread as you can.

This last observation prompted a haunting distillation by Lev Mirov of Odysseus’s journey and his encounter with the Sirens:

Back to Wilson, who translates the brutally short passage of the sirens this way:

She explains:

Translation is hard, but translation in public is harder and better. There’s a richness in the commentary, and also a reckoning with the accretion of meanings that have come down through past readings, that you don’t often get without diving into scholarly apparatus. It’s not just peeling back the plaster; it’s trying to understand the work that plaster did in holding the whole structure together. Just remarkable.

Update: Dan Chiasson wrote about Wilson’s use of Twitter for the New Yorker.

Stay Connected