A new history of late medieval Ethiopia and its interactions with Europe by historian Verena Krebs does something a little unusual, at least for a professor at a European university: it treats the horn of Africa as the center of civilization that it was, and Europeans as the members of far-flung satellite states that Ethiopians could not help but see them as being.

It’s not that modern historians of the medieval Mediterranean, Europe and Africa have been ignorant about contacts between Ethiopia and Europe; the issue was that they had the power dynamic reversed. The traditional narrative stressed Ethiopia as weak and in trouble in the face of aggression from external forces, especially the Mamluks in Egypt, so Ethiopia sought military assistance from their fellow Christians to the north—the expanding kingdoms of Aragon (in modern Spain), and France. But the real story, buried in plain sight in medieval diplomatic texts, simply had not yet been put together by modern scholars. Krebs’ research not only transforms our understanding of the specific relationship between Ethiopia and other kingdoms, but joins a welcome chorus of medieval African scholarship pushing scholars of medieval Europe to broaden their scope and imagine a much more richly connected medieval world.

The Solomonic kings of Ethiopia, in Krebs’ retelling, forged trans-regional connections. They “discovered” the kingdoms of late medieval Europe, not the other way around. It was the Africans who, in the early-15th century, sent ambassadors out into strange and distant lands. They sought curiosities and sacred relics from foreign leaders that could serve as symbols of prestige and greatness. Their emissaries descended onto a territory that they saw as more or less a uniform “other,” even if locals knew it to be a diverse land of many peoples. At the beginning of the so-called Age of Exploration, a narrative that paints European rulers as heroes for sending out their ships to foreign lands, Krebs has found evidence that the kings of Ethiopia were sponsoring their own missions of diplomacy, faith and commerce.

In fact, it would probably be accurate to say that Ethiopia (which over its long history has included areas now in Eritrea, Somalia, Sudan, Yemen, and parts of Saudi Arabia) was undergoing its own Renaissance, complete with the rediscovery of a lost classical kingdom, Aksum (sometimes called Axum).

Around the third century, Aksum was considered an imperial power on the scale of Rome, China, and Persia. It was part to better understand the historical legacy of Aksum that east Africans circa 1400 reestablished trading ties and military partnerships with their old Roman trading partners — or, in their absence, the Germanic barbarians who’d replaced them.

Europe, Krebs says, was for the Ethiopians a mysterious and perhaps even slightly barbaric land with an interesting history and, importantly, sacred stuff that Ethiopian kings could obtain. They knew about the Pope, she says, “But other than that, it’s Frankland. [Medieval Ethiopians] had much more precise terms for Greek Christianity, Syriac Christianity, Armenian Christianity, the Copts, of course. All of the Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches. But everything Latin Christian [to the Ethiopians] is Frankland.”

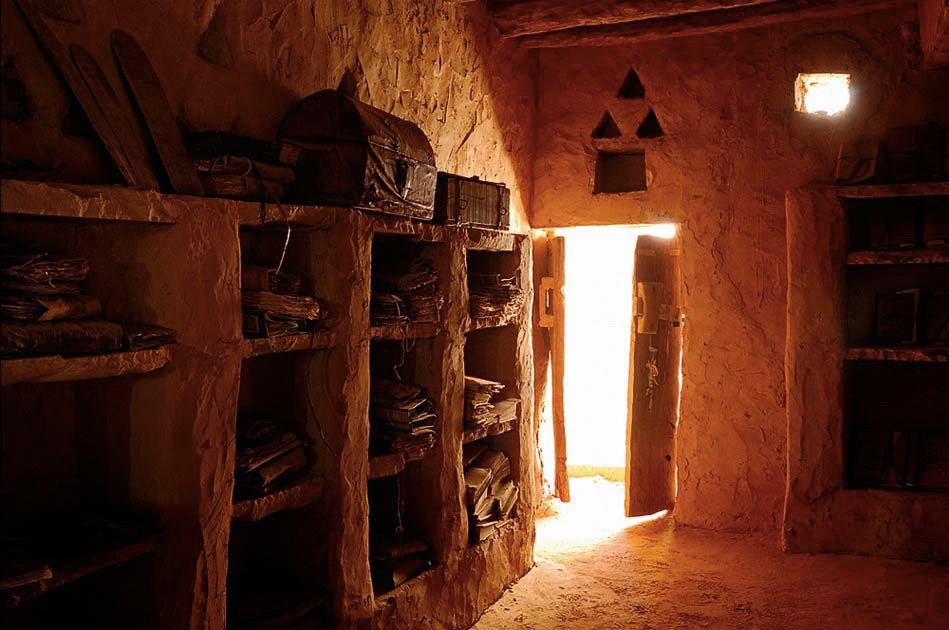

I did not know about these wonderful places. For hundreds of years, families in Mauritania have been maintaining libraries of old Arabo-Berber books. Originally on the route of pilgrims travelling to Mecca, the libraries are now at risk from the spreading Sahara and ever dwindling numbers of visitors, in part because of security restrictions due to terrorism.

This thread by Incunabla brought their existence to my attention.

Most of Chinguetti consists of abandoned houses which are being swallowed up by the ever encroaching dunes of the Sahara. But this was once a prosperous city of 20 000 people, and a medieval centre for religious and legal scholars. It was known as “The City of Libraries”.

Lower down the thread, we are directed to this piece at the Guardian, Mauritania’s hidden manuscripts.

The bone-dry wood creaks as the book opens at a page representing the course of the moon, framed by black balls and red crescents. The manuscript contains 132 pages of Arab astronomy bound in well-worn leather, a 15th-century treasure stored, with similar items, in a cardboard box in a traditional dwelling in Chinguetti.

Seen as a legacy from their ancestors, the families feel it’s an honour for them to care for these books.

About 600km north-east of the capital, in Chinguetti, once a centre of Islamic learning, the Habott family owns one of the finest private libraries, with 1,400 books covering a dozen subjects such as the Qur’an and the Hadith (the words of the Prophet), astronomy, mathematics, geometry, law and grammar. The oldest tome, written on Chinese paper, dates from the 11th century.

Also linked in the thread, more pictures at Messy Nessy.

Tomorrow, February 23, is William Edward Burghardt Du Bois’s birthday. Du Bois was born in 1868 and died in 1963. In fact, Du Bois died, in Ghana, the day before the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Roy Wilkins and hundreds of thousands of marchers observed Du Bois’s death with a moment of silence.

Du Bois is one of the most influential and important thinkers in American history. He wrote many, many speeches, essays, and books that are essential to understanding American culture, society, labor, and politics, particularly as they affected and were affected in turn by black people.

My favorite Du Bois essay, and one of the first I ever read, was and probably still is “Criteria of Negro Art.” It was written and published in 1926, and first presented as a speech in honor of Carter Woodson. I have in the last few years met otherwise extremely well-read people who knew nothing of this essay and have since sworn an oath to remedy that wherever possible. So you get to read some excerpts from it now.

The Big Idea of the essay is really formulated in the fourth paragraph:

What do we want? What is the thing we are after? As it was phrased last night it had a certain truth: We want to be Americans, full-fledged Americans, with all the rights of other American citizens. But is that all? Do we want simply to be Americans? Once in a while through all of us there flashes some clairvoyance, some clear idea, of what America really is. We who are dark can see America in a way that white Americans cannot. And seeing our country thus, are we satisfied with its present goals and ideals?

The answer to this first question “What do we want?” is Art, the proper appreciation of Beauty and Freedom; and the answer to the last question, “are we satisfied with [America’s] present goals and ideals?” is, of course, No.

In the twelfth paragraph, Du Bois argues that the lives of black Americans, not just the emerging intellectual bourgeoisie of the 1920s, but the lives of all black Americans, for their entire history, are the proper subject of this new kind of Art:

This is brought to us peculiarly when as artists we face our own past as a people. There has come to us — and it has come especially through the man we are going to honor tonight — a realization of that past, of which for long years we have been ashamed, for which we have apologized. We thought nothing could come out of that past which we wanted to remember; which we wanted to hand down to our children. Suddenly, this same past is taking on form, color, and reality, and in a half shamefaced way we are beginning to be proud of it. We are remembering that the romance of the world did not die and lie forgotten in the Middle Age [sic]; that if you want romance to deal with you must have it here and now and in your own hands.

Du Bois, after all, was a sociologist, and knew how to mobilize facts and figures; he does so in this anecdote, about black soldiers who fought in the Great War:

Have you heard the story of the conquest of German East Africa? Listen to the untold tale: There were 40,000 black men and 4,000 white men who talked German. There were 20,000 black men and 12,000 white men who talked English. There were 10,000 black men and 400 white men who talked French. In Africa then where the Mountains of the Moon raised their white and snow-capped heads into the mouth of the tropic sun, where Nile and Congo rise and the Great Lakes swim, these men fought; they struggled on mountain, hill and valley, in river, lake and swamp, until in masses they sickened, crawled and died; until the 4,000 white Germans had become mostly bleached bones; until nearly all the 12,000 white Englishmen had returned to South Africa, and the 400 Frenchmen to Belgium and Heaven; all except a mere handful of the white men died; but thousands of black men from East, West and South Africa, from Nigeria and the Valley of the Nile, and from the West Indies still struggled, fought and died. For four years they fought and won and lost German East Africa; and all you hear about it is that England and Belgium conquered German Africa for the allies!

In the 18th paragraph, he demolishes the premise that the success of black artists in and of itself is evidence of racial progress as such:

With the growing recognition of Negro artists in spite of the severe handicaps, one comforting thing is occurring to both white and black. They are whispering, “Here is a way out. Here is the real solution of the color problem. The recognition accorded Cullen, Hughes, Fauset, White and others shows there is no real color line. Keep quiet! Don’t complain! Work! All will be well!”

And beginning in the 21st paragraph, he quickly, and with startling beauty, poses the real problem for black artists working in America:

There is in New York tonight a black woman molding clay by herself in a little bare room, because there is not a single school of sculpture in New York where she is welcome. Surely there are doors she might burst through, but when God makes a sculptor He does not always make the pushing sort of person who beats his way through doors thrust in his face. This girl is working her hands off to get out of this country so that she can get some sort of training.

There was Richard Brown. If he had been white he would have been alive today instead of dead of neglect. Many helped him when he asked but he was not the kind of boy that always asks. He was simply one who made colors sing.

There is a colored woman in Chicago who is a great musician. She thought she would like to study at Fontainebleau this summer where Walter Damrosch and a score of leaders of Art have an American school of music. But the application blank of this school says: “I am a white American and I apply for admission to the school.”

We can go on the stage; we can be just as funny as white Americans wish us to be; we can play all the sordid parts that America likes to assign to Negroes; but for any thing else there is still small place for us.

I first read this essay at least twenty years ago, but I swear I’ve thought about “when God makes a sculptor He does not always make the pushing sort of person who beats his way through doors thrust in his face” every day since. Every day. I think about it for black artists, for gay, lesbian, transgender, and queer artists, for women who put up with harassment and abuse from the very people who’ve promised to help them pursue their art. And I think about it even more when I think about the thousands if not millions of people who were turned away from ever becoming artists, writers, musicians, actors, sculptors, dancers, engineers, designers, programmers, or any other critical or creative field where doors are so often thrust in your face.

Yes, push through those doors. But hold them open after you. Because the next person, God may not have made to be one whose first inclination is to push.

All art, Du Bois argues, and in particular the art of black people, relies on not just Beauty, but Truth and Goodness, “goodness in all its aspects of justice, honor and right — not for sake of an ethical sanction but as the one true method of gaining sympathy and human interest.” Art that seeks to restore the balance of truth and goodness, on a subject like the lives of black people, which is prone to so much distortion and misunderstanding, necessarily relies on an ideal of Justice. This leads to maybe the most famous quote of the essay:

Thus all Art is propaganda and ever must be, despite the wailing of the purists. I stand in utter shamelessness and say that whatever art I have for writing has been used always for propaganda for gaining the right of black folk to love and enjoy. I do not care a damn for any art that is not used for propaganda. But I do care when propaganda is confined to one side while the other is stripped and silent.

What America is getting from its white artists, is propaganda that shames and distorts the lives of black people, in order to show them to be sinister and/or servile.

In other words, the white public today demands from its artists, literary and pictorial, racial pre-judgment which deliberately distorts Truth and Justice, as far as colored races are concerned, and it will pay for no other.

But respectability politics is almost as dangerous, when it comes to art.

On the other hand, the young and slowly growing black public still wants its prophets almost equally unfree. We are bound by all sorts of customs that have come down as second-hand soul clothes of white patrons. We are ashamed of sex and we lower our eyes when people will talk of it. Our religion holds us in superstition. Our worst side has been so shamelessly emphasized that we are denying we have or ever had a worst side. In all sorts of ways we are hemmed in and our new young artists have got to fight their way to freedom.

And here is the bind, the contradiction which even Du Bois cannot completely unravel. Until black artists produce great art, black people will not be registered by white people as fully human. And once those great artists appear, their blackness will be erased away, in favor of a false universality and sham humanism.

And then do you know what will be said? It is already saying. Just as soon as true Art emerges; just as soon as the black artist appears, someone touches the race on the shoulder and says, “He did that because he was an American, not because he was a Negro; he was born here; he was trained here; he is not a Negro — what is a Negro anyhow? He is just human; it is the kind of thing you ought to expect.”

I do not doubt that the ultimate art coming from black folk is going to be just as beautiful, and beautiful largely in the same ways, as the art that comes from white folk, or yellow, or red; but the point today is that until the art of the black folk compells [sic] recognition they will not be rated as human. And when through art they compell [sic] recognition then let the world discover if it will that their art is as new as it is old and as old as new.

Du Bois closes the essay with one of the most beautiful passages I’ve ever read. It’s also the most personal. It’s about his friend and classmate William Vaughan Moody.

I had a classmate once who did three beautiful things and died. One of them was a story of a folk who found fire and then went wandering in the gloom of night seeking again the stars they had once known and lost; suddenly out of blackness they looked up and there loomed the heavens; and what was it that they said? They raised a mighty cry: “It is the stars, it is the ancient stars, it is the young and everlasting stars!”

There are other great essays about the relationship between politics and art. Some of them are subtler than Du Bois’s. Some take on more directly the nature of politics or art itself. Some have a more politically radical intent. Some name more names, and pick more fights. But nobody but Du Bois, working with the economy he’s working with, states as directly the political problems facing art, artists, art critics, and the art-loving public. Nobody gets to the root of things as squarely as he does.

It’s the best essay on art and politics ever written. And if you don’t agree, I want to see your candidate. That’s all.

The oldest known fossils of homo sapiens have been found in Morocco. The bones date back to ~300,000 years ago, more than 100,000 years earlier than previous fossils found. Here’s Carl Zimmer reporting for the NY Times about the paper in Nature:

Dating back roughly 300,000 years, the bones indicate that mankind evolved earlier than had been known, experts say, and open a new window on our origins.

The fossils also show that early Homo sapiens had faces much like our own, although their brains differed in fundamental ways.

Until now, the oldest fossils of our species, found in Ethiopia, dated back just 195,000 years. The new fossils suggest our species evolved across Africa.

“We did not evolve from a single cradle of mankind somewhere in East Africa,” said Phillipp Gunz, a paleoanthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Liepzig, Germany, and a co-author of two new studies on the fossils, published in the journal Nature.

The previous oldest fossils were found clear across the continent in Ethiopia, in eastern Africa. From a New Yorker article on the discovery:

And the specimens in question were found not in East Africa, which has become synonymous with a sort of paleoanthropological Garden of Eden, but clear on the other side of the continent — and the Sahara — in Morocco. “We’re not claiming that Morocco is the cradle of modern humankind,” the lead author, Jean-Jacques Hublin, of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, said at a press conference yesterday. Rather, he added, our emergence as a species was pan-African. “There is no Garden of Eden in Africa — or if there is, it’s Africa,” Hublin said. “The Garden of Eden is the size of Africa.”

On the one hand, you’ve got the good. On the other hand, you have the bad. And then there’s a bunch of stuff in the middle. I was in the middle for a long time. Most of my life actually…just sort of floating nonchalantly along.

Then life got weird. Ever since, I’ve been oscillating between the good and the bad, swinging (sometimes violently) back and forth from one extreme to the other. This weekend, I felt as bad as I’ve ever felt in my life. Despair the size of a watermelon. But, I also felt as good as I ever felt this weekend. Happiness you only see in the face of a small child during a really ripping game of Peek-a-boo.

And this existance is really different for me…I used to be on cruise control, but now I’m driving in the city, stopping and starting again at all the intersections. I really don’t know where I’m going to end up. Is all this oscillating going to rip me apart or will I settle on one or the other or end up somewhere in the middle again?

Right now, the good is far outpacing the bad…and I think that trend will continue for a while.

Stay Connected