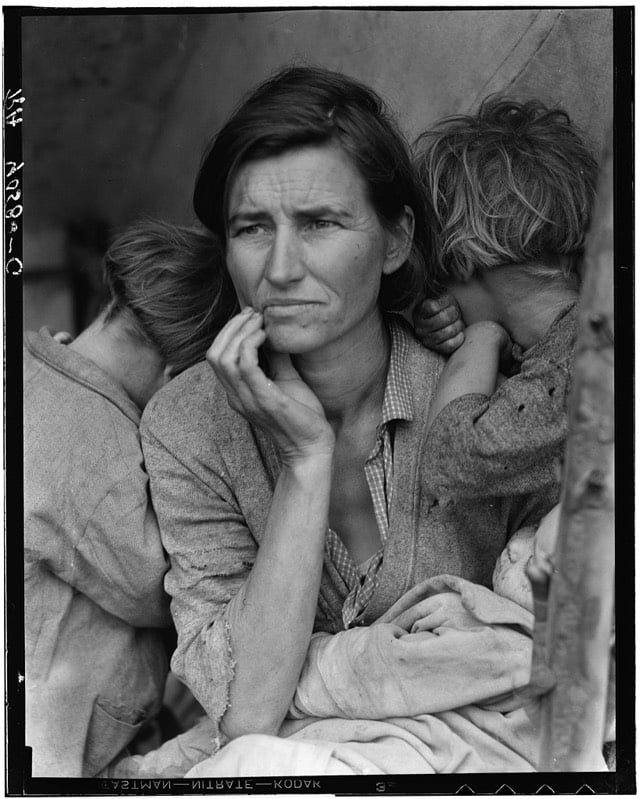

The Making of an Iconic Photograph: Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother

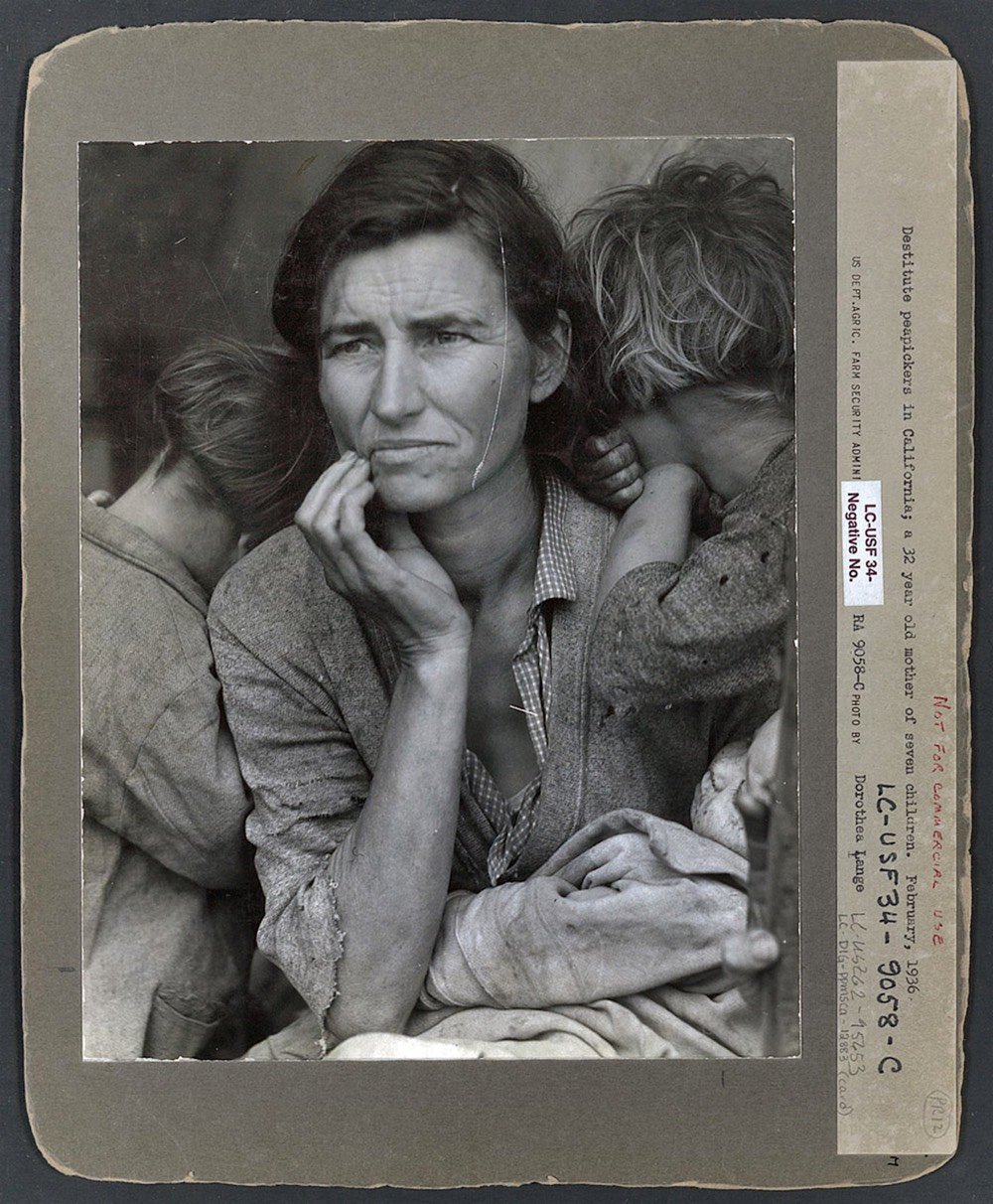

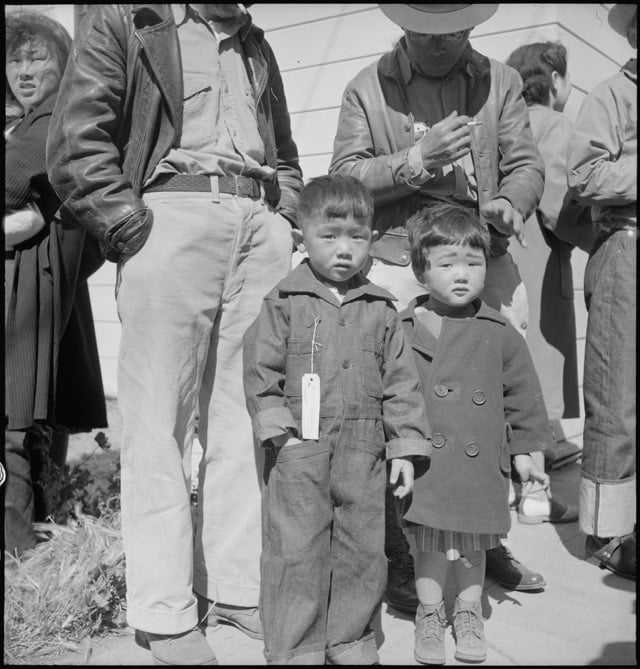

At the end of a long day in March 1936, Dorothea Lange stopped in a migrant workers camp in California for just 10 minutes and took six photos of a woman and her children. The final photo, known as Migrant Mother, became one of the most iconic photographs of the Great Depression.

In this video, Evan Puschak details not only the context the photo was created under (FDR’s administration wanted photos that would shift public support towards providing government aid) but also how Lange stage-managed the scene to get the shot she wanted.

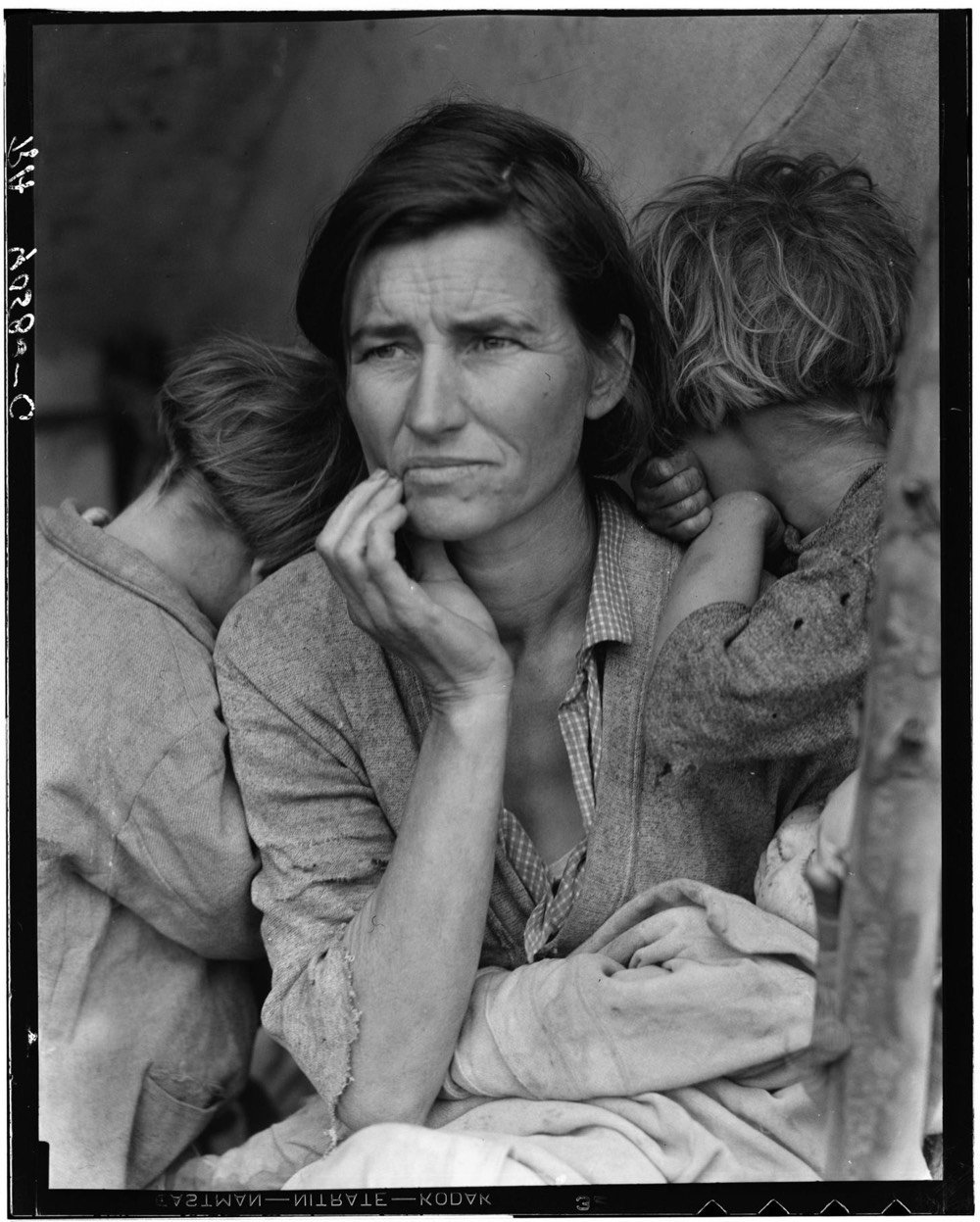

As Puschak notes, the photo we are all familiar with was retouched three years after its initial publication to remove what Lange saw as a detriment to the balance of the scene: the thumb of the woman’s hand holding the tent post in the lower right-hand corner.

It is easy to tell whether a print of “Migrant Mother” was made before 1939, because that year Ms. Lange had an assistant retouch the negative and remove Ms. Thompson’s thumb from the bottom right corner, much to the chagrin of Roy Stryker, her boss at the Farm Security Administration. While that was a fairly common practice at the time, Mr. Stryker thought it compromised the authenticity not just of the photo but also of his whole F.S.A. documentary project, Ms. Meister said. But Ms. Lange considered the thumb to be such a glaring defect that she apparently didn’t have a second thought about removing it.

Here’s what it looked like before the alteration:

There are some other things about the photo that may prompt us to think about the objectivity of documentary photography. The cultural story of Migrant Mother is that this is a white woman who came west during the Great Depression for migrant work. The real story is more complicated. The woman was identified in the late 1970s as Florence Owens Thompson, and as she told her story, we learned some things that Lange didn’t have time to discover during her fleeting time at the camp:

1. Thompson was a full-blooded Cherokee born in Indian Territory (which later became the state of Oklahoma). As this NY Times review of Sarah Meister’s book on the photograph says, if people had known the woman wasn’t white, the photo may not have had the impact it did.

“We have never been a race-blind country, frankly,” Ms. Meister said. “I wish that I could say that the response would have been the same if everyone had been aware that she was Cherokee, but I don’t think that you can.”

2. The family were not recent migrants to California and had actually moved from Oklahoma in 1926, well before the Depression started. The family briefly moved back to Oklahoma because Thompson was pregnant and afraid the father’s family would take the baby from her, but returned to California in 1934.

3. Thompson’s first husband died in 1931 of tuberculosis while she was pregnant with her sixth child. A seventh child resulted from a brief relationship with the father mentioned above. An eighth child followed by a new husband in 1935. But it was Thompson who provided for the family while taking care of 8 kids:

By all accounts, Jim Hill was a nice guy from a respectable family who never could seem to get his act together. “I loved my dad dearly,” Norma Rydlewski said, “but he had little ambition. He was never was able to hold down a job.” The burden of supporting the family, and of keeping it together, fell on Florence.

4. The ultimate goal of Lange taking Thompson’s photo for the FSA was to stimulate public support for government aid to people who were out of work because of the Depression. But Thompson herself didn’t want any aid:

“Her biggest fear,” recalled son Troy Owens, “was that if she were to ask for help [from the government], then they would have reason to take her children away from her. That was her biggest fear all through her entire life.”

5. Thompson and her family weren’t actually living at the pea pickers camp when Lange photographed them there. They had just stopped temporarily to fix their car and were only there for a day or two.

In the field notes that she filed with her Nipomo photographs, Lange included the following description: “Seven hungry children. Father is native Californian. Destitute in pea pickers’ camp … because of failure of the early pea crop. These people had just sold their tires to buy food.”

Owens scoffed at the description. “There’s no way we sold our tires, because we didn’t have any to sell,” he told this writer. “The only ones we had were on the Hudson and we drove off in them. I don’t believe Dorothea Lange was lying, I just think she had one story mixed up with another. Or she was borrowing to fill in what she didn’t have.”

“Mother always said that Lange never asked her name or any questions, so what she [Lange] wrote she must have got from the older kids or other people in the camp,” speculates daughter Katherine McIntosh, who appears in the Migrant Mother photo with her head turned away behind her mother’s right shoulder. “She also told mother the negatives would never be published — that she was only going to use the photos to help out the people in the camp.”

So what are we to make of what we thought we knew about this photograph and what we know now? In 2009, Errol Morris wrote of the FSA photos:

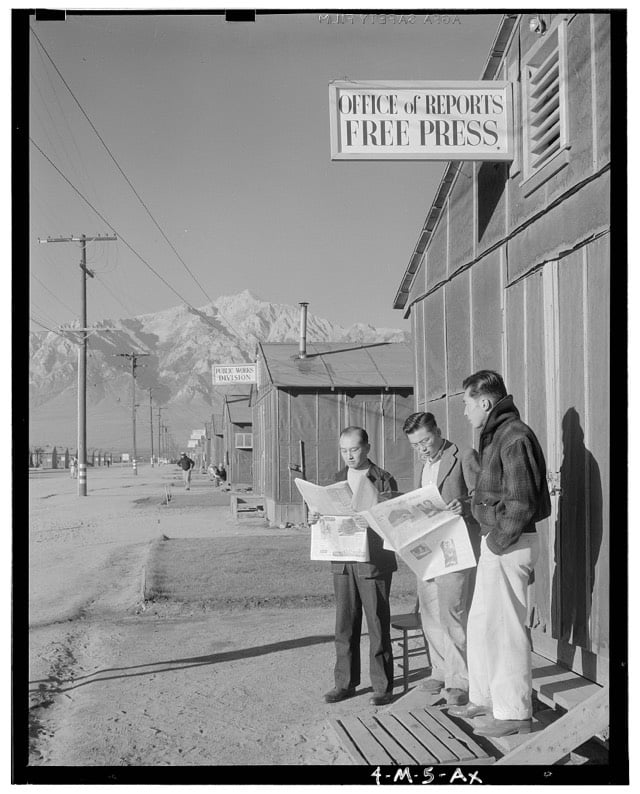

Rothstein, Lange and Evans have been accused of posing their photographs, in short, of manipulating them to some end. And yet all photographs are posed. There is no such thing as pure documentary photography. The problem is not in what any of them have done, but in our misunderstanding of photography. No crimes were committed by the F.S.A. photographers. They labored as employees of an organization dedicated to providing propaganda for the Roosevelt administration. And they created some of the greatest photographs in American history. Photographs can be works of art, bearers of evidence, and a connection with the past for individuals, families and society as a whole. It should not be lost on any of us that these controversies are still with us. The Photoshop alteration of a photograph “documenting” the launching of Iranian missiles, the cropping of a Christmas get-together at the Cheney ranch. These are just the latest iterations. In 1936, Roosevelt was reelected in a contentious election. Photography played a controversial role, reminding us that wherever there are intense disagreements, particularly political disagreements, there will be disagreements about photography, as well.

The stories we tell about photographs change as we change and as our culture changes. Yes, Migrant Mother is a symbol of the hardship endured by many during the Great Depression. But Migrant Mother is also the portrait of a fiercely independent Native American single mother who fought to provide for her family and keep them together during the most difficult time in our nation. That’s a story worth hearing today.

Both prints above are courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division: with thumb and without. You can also explore the rest of the LOC’s FSA collection.

Stay Connected