Ghanaian sculptor Paa Joe makes coffins (both human-sized and mini sculptures) modeled after real-life objects that were important to the deceased. He just opened his first NYC solo show at Superhouse; from their description of his work:

Paa Joe is a second-generation fantasy coffin maker, contributing to an artistic tradition of great importance around Ghana’s capital, Accra. Known as abeduu adeka, or proverb boxes, these end-of-life vessels illustrate Ghanaian beliefs concerning life and death. Since the 1960s, the artist has meticulously carved and painted figurative coffins, representing various living and inanimate objects symbolizing the deceased (an onion for a farmer, an eagle for a community leader, a sardine for a fisherman, etc.).

You read more about Paa Joe’s work and see more of his pieces at The Guardian:

“People celebrate death in Ghana. At a funeral, we have a passion for the person leaving us - there are a lot of people, and a lot of noise,” says Jacob, 28, who has worked with his father for eight years.

Far from seeing their work as morbid, Jacob says the coffins are celebratory and reflect west African attitudes to death. “It reminds people that life continues after death, that when someone dies they will go on in the afterlife, so it is important that they go in style.”

And at The Future Perfect, Fad, Hypebeast, and on Instagram. (via @presentandcorrect)

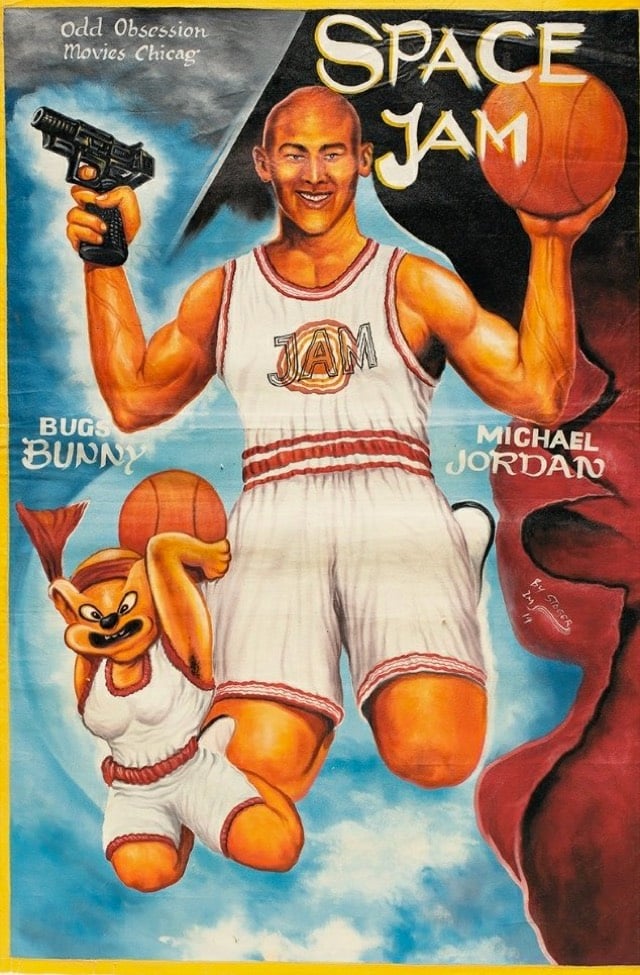

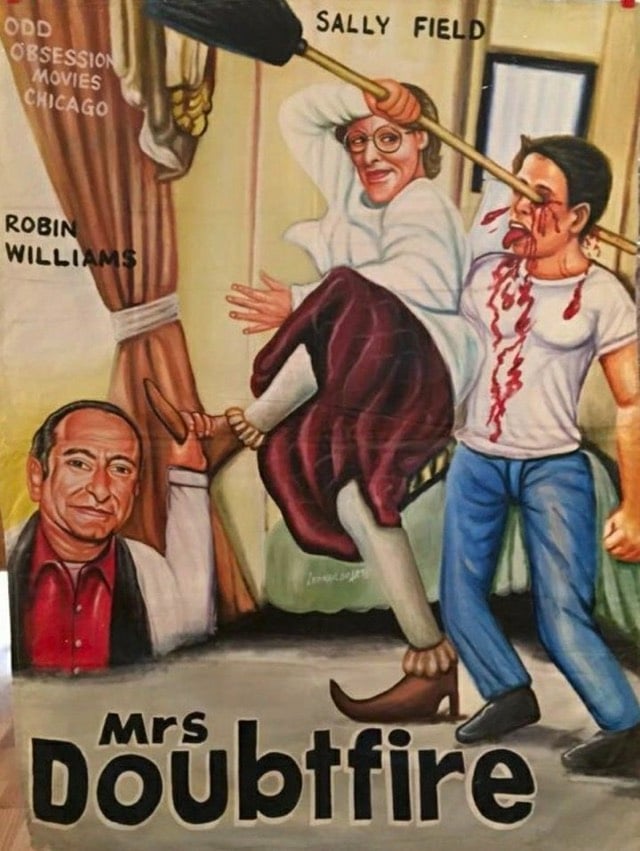

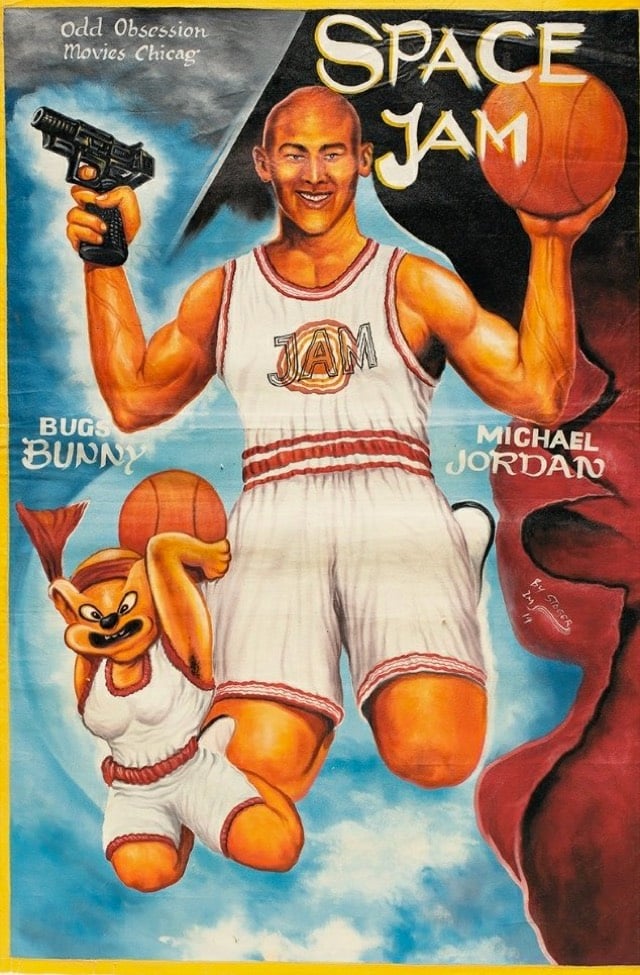

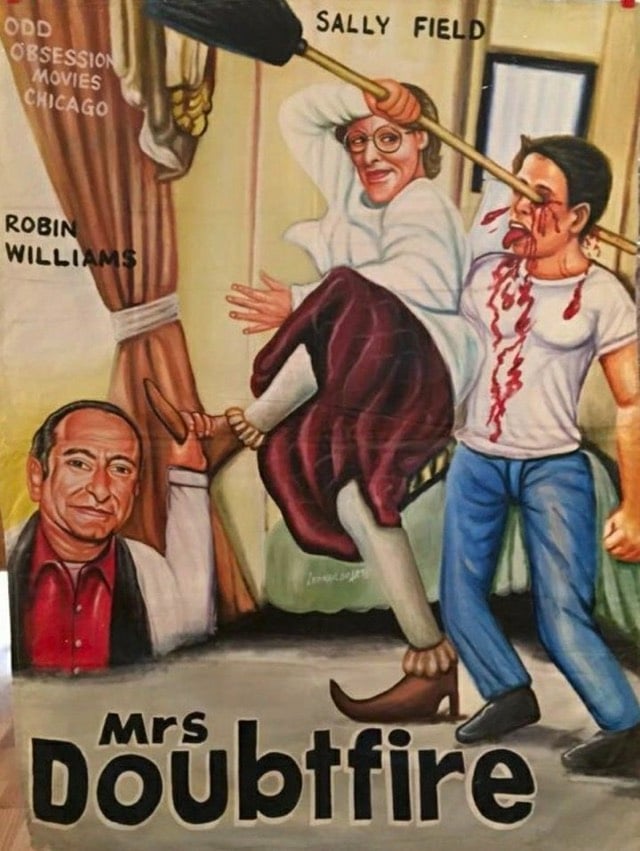

In order to drum up business for local movie theaters in Africa (most notably in Ghana), theater owners would commission local artists to paint movie posters.

When Frank Armah began painting posters for Ghanaian movie theaters in the mid-1980s, he was given a clear mandate: Sell as many tickets as possible. If the movie was gory, the poster should be gorier (skulls, blood, skulls dripping blood). If it was sexy, make the poster sexier (breasts, lots of them, ideally at least watermelon-sized). And when in doubt, throw in a fish. Or don’t you remember the human-sized red fish lunging for James Bond in The Spy Who Loved Me?

“The goal was to get people excited, curious, to make them want to see more,” he says. And if the movie they saw ended up surprisingly light on man-eating fish and giant breasts? So be it. “Often we hadn’t even seen the movies, so these posters were based on our imaginations,” he says. “Sometimes the poster ended up speaking louder than the movie.”

You can check out more of these amazing artworks in this Twitter thread, this BBC story, on the AIGA site, and at Poster House, which has an exhibition of these posters up through Feb 16.

Update: I removed this modern-day spoof of the Ghanaian posters from the post. The tell is the reference to this amazing GIF. (thx, erik)

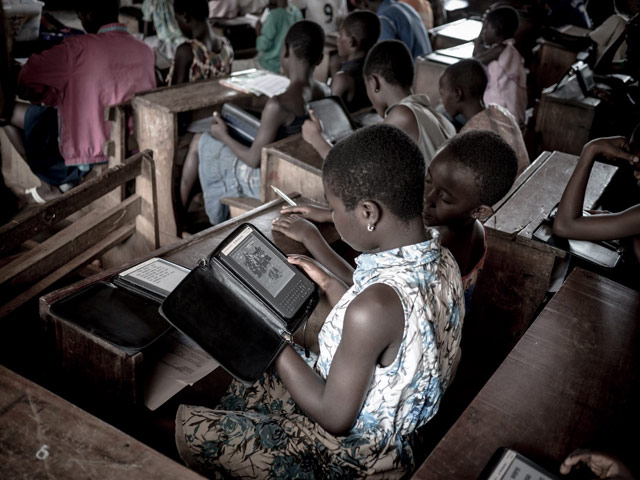

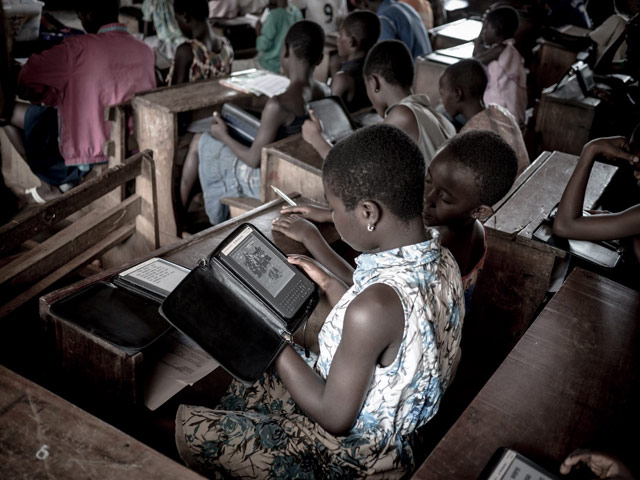

Craig Mod visited Ghana recently to check on the progress of Worldreader, an organization dedicated to distributing digital books to children and families in places like Rwanda, Ghana, and South Africa.

Those of us who work in technology tend to take religious-like stances over its ability to change the world, always for the better. My paranoia of trickery comes from an inherent suspicion towards technology, and an even deeper suspicion of presuming to know better. It’s too easy to fall into the first-world trope of “all the poor need is a little sprinkling of silicon and then everything will be fine.” It’s never that simple. Technology is, at best, the tip of the iceberg. A very tiny component of the work that needs to be done in the greater whole of reforming or impacting or increasing accessibility to education, first-world and third-world alike. Technology deployed without infrastructure, without understanding, without administrative or community support, without proper curriculum is nearly worthless. Worse than worthless, even — for it can be destructive, the time and budget spent on the technology eating into more fundamental, more meaningful points of badly needed reform.

Stay Connected