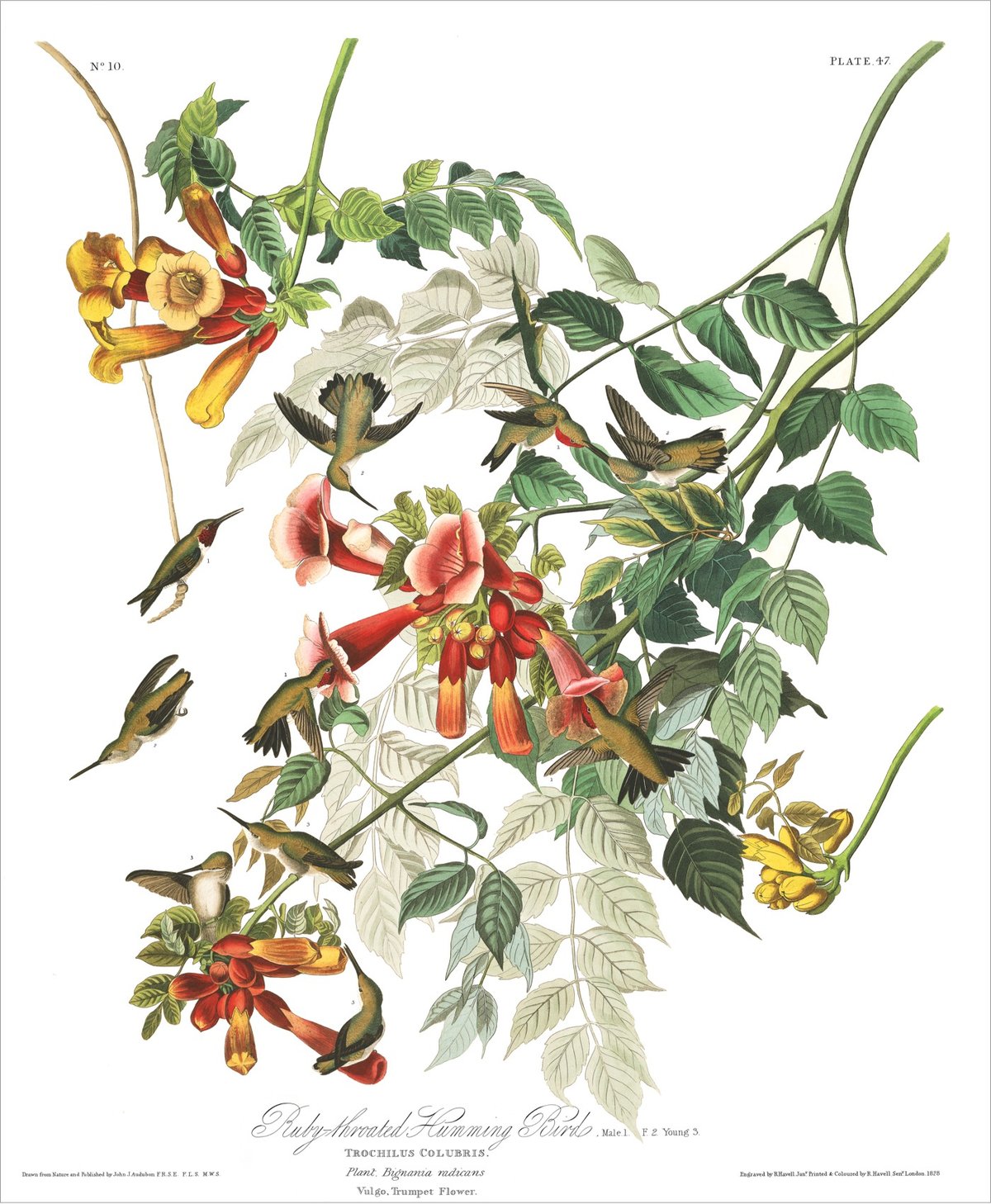

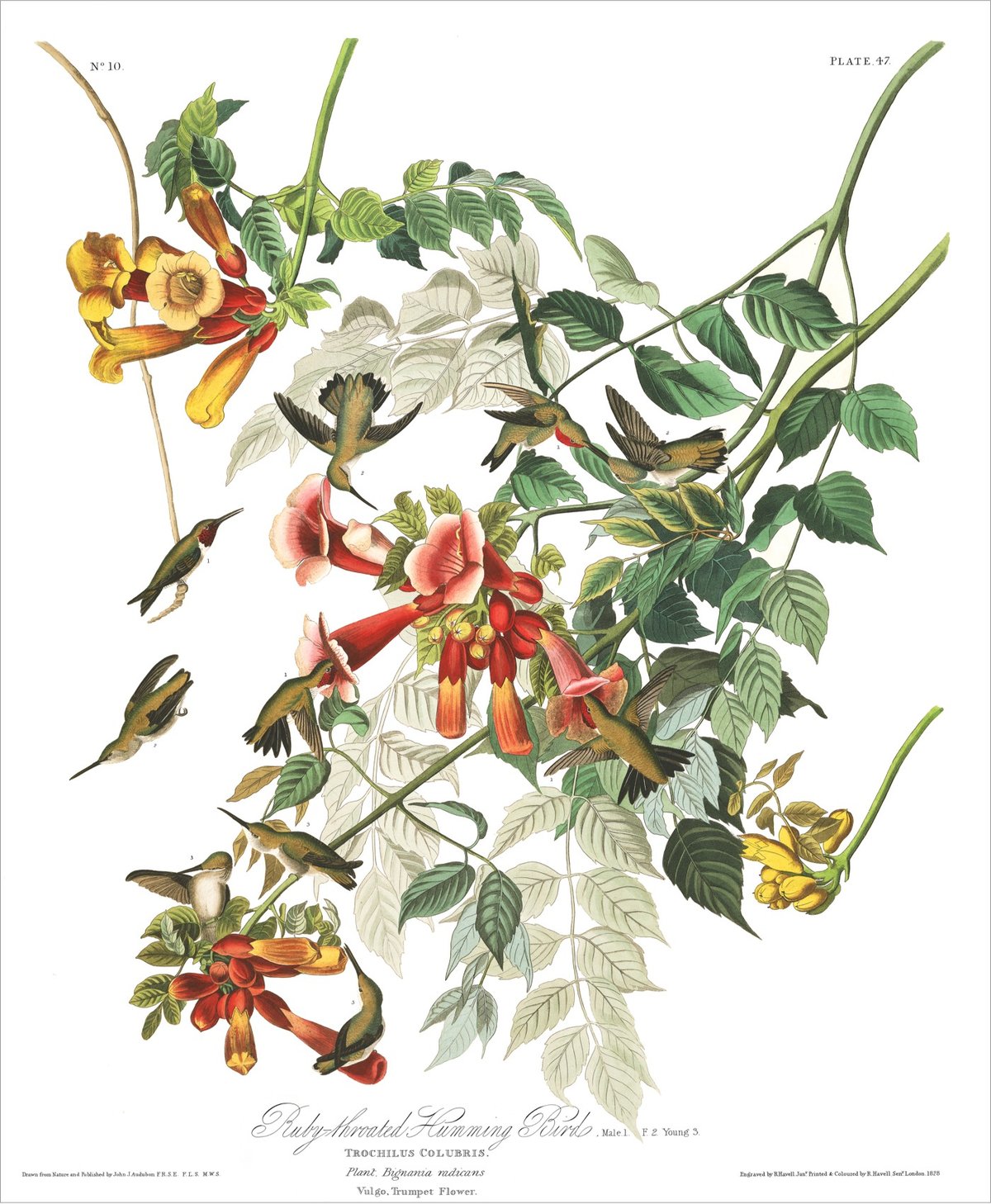

One of the (several dozen) posts I started writing ages ago but never finished was a collection of the hundreds of bird illustrations pictured in John James Audubon’s seminal Birds of America. The images have been floating around on the web forever, in various sizes and collections, and I wanted to group (or at least link to) all of them in one place. But now I don’t have to because the Audubon Society has put them up on their website.

John James Audubon’s Birds of America is a portal into the natural world. Printed between 1827 and 1838, it contains 435 life-size watercolors of North American birds (Havell edition), all reproduced from hand-engraved plates, and is considered to be the archetype of wildlife illustration.

Thumbnails of all 435 illustrations are presented on a single page (sortable alphabetically or chronologically by their creation date) and then each illustration is given its own page with Audubon’s notes on the bird pictured, a link to the bird in Audubon’s Bird Guide (where you can see photos and hear bird calls, etc.), and a link to download a high resolution image (if you sign up for their mailing list). The barred owl image is 111-megapixels. What a resource!

You can also see online copies of Birds of America at the University of Pittsburgh and Meisei University.

And if you’ve never had a chance to see some of these illustrations in real life, you should keep your eyes peeled for the opportunity. They really are something. (via open culture, which has been particularly great lately)

Over a period of thirteen years beginning in the 1820s, John James Audubon painted 435 different species of American birds.1 When he was finished, the illustrations were compiled into The Birds of America, one of the most celebrated books in American naturalism. Curiously however, five of the birds Audubon painted have never been identified: Townsend’s Finch, Cuvier’s Kinglet, Carbonated Swamp Warbler, Small-headed Flycatcher and Blue Mountain Warbler.

These birds have never been positively identified, and no identical specimens have been confirmed since Audubon painted them. Ornithologists have suggested that they might be color mutations, surviving members of species that soon became extinct, or interspecies hybrids that occurred only once.

The specimen that Audubon used to paint Townsend’s Bunting is now in the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, identified as Townsend’s Dickcissel, but no bird exactly like it has been reported, Dr. Olson, an authority on Audubon’s work, noted in an email. Ornithologists suggest that it is either a mutation of the Dickcissel or a hybrid of Dickcissel and Blue Grosbeak, she said.

And that’s not counting the ones he got wrong for other reasons:

And indeed, there are several birds painted and explained in Birds of America that are not, in fact, actual species. Some are immature birds mistaken for adults of a new species (the mighty “Washington’s Eagle” was, in all likelihood, an immature Bald Eagle). Some were female birds that didn’t look anything like their male partners (“Selby’s Flycatcher” was a female Hooded Warbler).

Audubon also painted six species of bird that have since become extinct: Carolina parakeet, passenger pigeon, Labrador duck, great auk, Eskimo curlew, and pinnated grouse. Here’s his portrait of the passenger pigeon:

There were an estimated 3 billion passenger pigeons in the world in the early 1800s — about one in every three birds in North America was a passenger pigeon at the time. Their flocks were so large, it took hours and even days for them to pass. Audubon himself observed in 1813:

I dismounted, seated myself on an eminence, and began to mark with my pencil, making a dot for every flock that passed. In a short time finding the task which I had undertaken impracticable, as the birds poured in in countless multitudes, I rose and, counting the dots then put down, found that 163 had been made in twenty-one minutes. I traveled on, and still met more the farther I proceeded. The air was literally filled with Pigeons; the light of noon-day was obscured as by an eclipse; the dung fell in spots, not unlike melting flakes of snow, and the continued buzz of wings had a tendency to lull my senses to repose… I cannot describe to you the extreme beauty of their aerial evolutions, when a hawk chanced to press upon the rear of the flock. At once, like a torrent, and with a noise like thunder, they rushed into a compact mass, pressing upon each other towards the center. In these almost solid masses, they darted forward in undulating and angular lines, descended and swept close over the earth with inconceivable velocity, mounted perpendicularly so as to resemble a vast column, and, when high, were seen wheeling and twisting within their continued lines, which then resembled the coils of a gigantic serpent… Before sunset I reached Louisville, distant from Hardensburgh fifty-five miles. The Pigeons were still passing in undiminished numbers and continued to do so for three days in succession.

100 years later, they were all dead. Which may have had at least one interesting consequence:

But the sad echo of the loss of passenger pigeons still reverberates today because its extinction probably exacerbated the proliferation of Lyme disease. When the passenger pigeons existed in large numbers, they subsisted primarily on acorns. However, since there are no pigeons to eat acorns, the populations of Eastern deer mice — the main reservoir of Lyme disease — exploded far beyond historic levels as they exploited this unexpected food bonanza.

Stay Connected