kottke.org posts about Snapchat

I know this probably isn’t brand new, but in the past couple of weeks I’ve noticed a few articles published by big media companies that are influenced by the design of Snapchat and Instagram Stories. Just to be clear, these aren’t published on Instagram (that’s been going on for years); they are published on media sites but are designed to look and work like Instagram Stories. The first one I noticed was this NY Times piece on Guantanamo Bay.

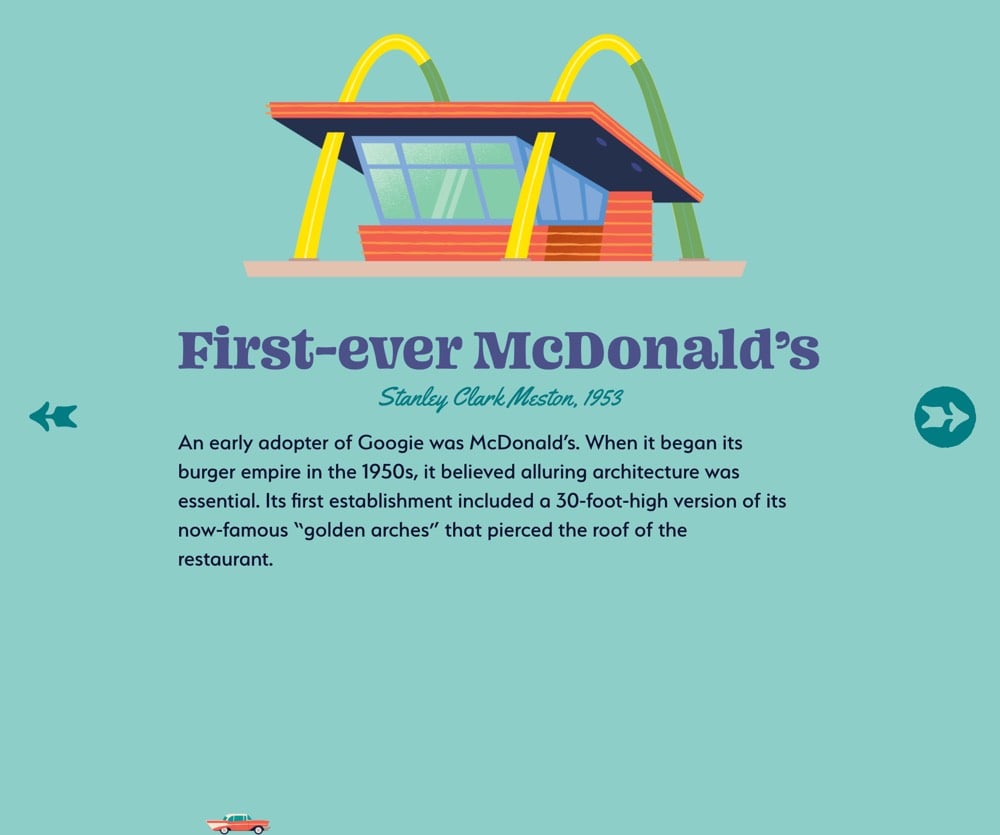

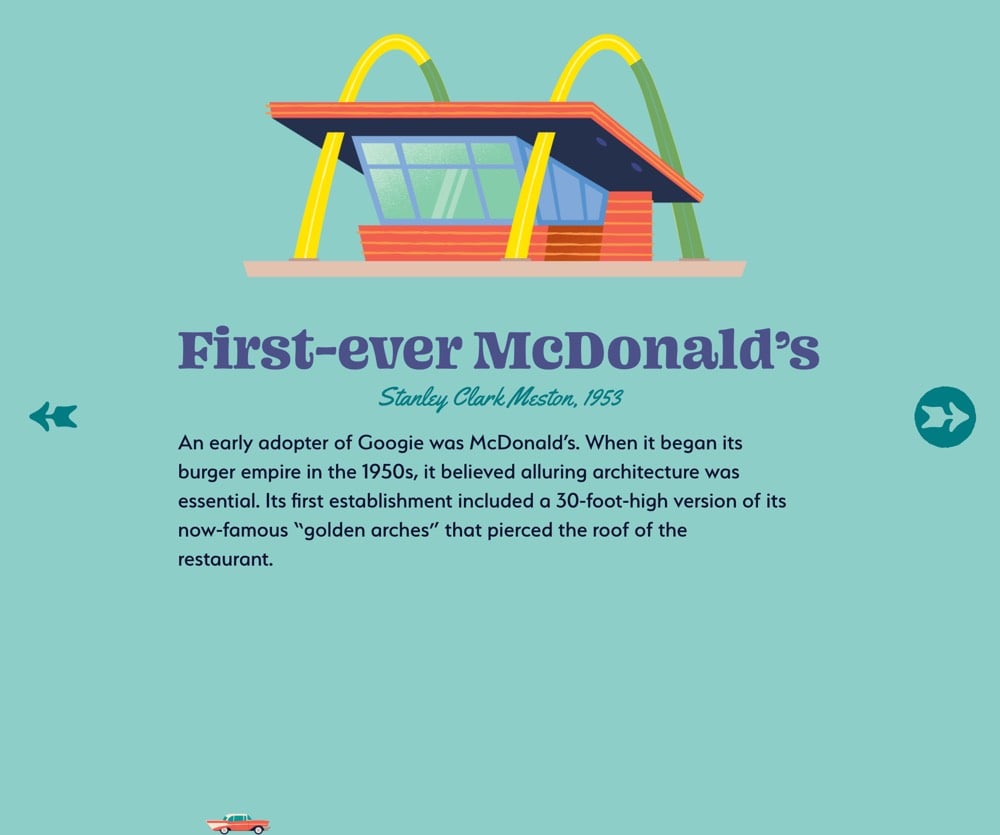

You can see the Instagram-style progress meter at the top. And then there’s Curbed’s The Ultimate Guide to Googie, where the progress meter is indicated more playfully by the little car at the bottom (it even switches directions based on whether you’re paging forward or back through the story). Curbed EIC Kelsey Keith says it was built using “Vox Media’s new custom storytelling kit tool”.

The third piece I can’t find again — I think it was a WSJ or Washington post article — but it too was influenced by the Stories format.

It’s a good move for these companies. Snap & Instagram have worked hard to pioneer and promote this format, it’s perfectly designed for mobile, and people (especially younger folks) know how to use it. Nominally, these articles are just slideshows, a format that online media companies have been using forever. But I’d argue there are some important differentiators that point to the clear influence of Instagram and to this being a newish trend:

1. The presentation is edge to edge with full-frame photos and auto-playing videos.

2. There’s no “chrome” as there would be around a slideshow and minimal indication of controls.

3. They read best on mobile devices in portrait mode.

4. The display of progress meters.

5. Navigation by swiping or tapping on the far left or right sides of the screen, especially on mobile.

Have you seen any other examples of media companies borrowing the Stories design from Instagram?

Update: Various media outlets are using Google’s AMP Stories to make these. You can see examples on CNN, the Atlantic, and Wired.

This is likely what my mystery third story was built with. (via @adamvanlente)

Every time there’s a new social media app or network that breaks out, someone writes an article about how this new network encourages people to be themselves and have fun without all of the heaviness of other platforms. The latest example of this is Kevin Roose’s NY Times piece about TikTok.

TikTok has none of that. Instead, it’s that rarest of internet creatures: a place where people can let down their guards, act silly with their friends and sample the fruits of human creativity without being barraged by abusive trolls or algorithmically amplified misinformation. It’s a throwback to a time before the commercialization of internet influence, when web culture consisted mainly of harmless weirdos trying to make each other laugh.

In 2016, Jenna Wortham wrote this about Snapchat for the NY Times:

Its entire aesthetic flies in the face of how most people behave on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter — as if we’re waiting to be plucked from obscurity by a talent agent or model scout. But Snapchat isn’t the place where you go to be pretty. It’s the place where you go to be yourself, and that is made easy thanks to the app’s inbuilt ephemerality.

In 2013, Mat Honan wrote this about Vine:

It built a ground up culture that feels loose, informal, and — frankly — really fucking weird. Moreover, most of what you see there feels very of-the-moment. Sure, there’s plenty of artistry that goes into making six second loops, and there are volumes of videos with high production values. But far more common are Vines that serve as windows into what people are doing right now.

Implicit in these pieces is the idea that there’s something intrinsic to these apps/networks that makes them hew closer to real life and/or lightheartedness than older and bigger platforms…the ephemerality of Snapchat, the ease of shooting a Vine video, the fun filters and templates of TikTok. Some part of that is surely true, but what if being small and new is the thing that makes these networks fun? As I wrote in response to Wortham’s article a couple of years ago:

Blogs, Flickr, Twitter, Vine, and Instagram all started off as places to be yourself, but as they became more mainstream and their communities developed behavioral norms, the output became more crafted and refined. Users flooded in and optimized for what worked best on each platform. Blogs became more newsy and less personal, Flickr shifted toward professional-style photography, Vine got funnier, and Twitter’s users turned toward carefully crafted cultural commentary and link sharing. Editing worked its way in between the making and sharing steps.

TikTok probably feels a lot like Flickr or Twitter in the early days, where everyone is exploring and the users are all kind of doing the same things with it. As networks get bigger, they reach a point where there isn’t just one big group exploring the same space together. Instead, you have many big groups who have different goals and desires that all need to fit under one roof (essentially, politics becomes necessary)…and that can get messy, particularly when the companies running these apps want to appeal to the widest possible audience for capitalization purposes.

Novelty is probably the biggest factor though. TikTok is fun because it’s new. When you join up, you get new superpowers and flexing those abilities gives the old brain a shot of dopamine, particularly when the flexing is social. Later, when many of the social possibilities have been explored and even exploited, fun becomes harder to come by. Even Twitter can still be fun — see the replies to Wortham’s recent tweet about fave NYC moments — but the templates for interaction on the platform have long since been set in stone. It would be very surprising if a large & mature social network came along that didn’t also get less fun and “real” as it developed. That would be a special achievement.

Alec Garcia has built an extension for Chrome that lets you view the Instagram Stories of the people you follow. You can even save/download them.

BTW, I am really liking Instagram Stories. Yeah, sure, Snapchat rip-off blah blah blah,1 but Insta nailed the implementation and my network is already all there, so yeah. I’ve been posting occasional Stories, which you can see if you follow me on Instagram.

And yes, like Craig Mod, I use Instagram’s website many times a day. What percentage of their users even knows they can check Instagram on the web? 50%? 30%? 10%?

From the NY Times, the excellent Jenna Wortham on How I Learned to Love Snapchat. This bit caught my eye:

Its entire aesthetic flies in the face of how most people behave on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter — as if we’re waiting to be plucked from obscurity by a talent agent or model scout. But Snapchat isn’t the place where you go to be pretty. It’s the place where you go to be yourself, and that is made easy thanks to the app’s inbuilt ephemerality.

I wonder if Snapchat’s intimacy is entirely due to the ephemerality and lack of a “fave-based economy”. Blogs, Flickr, Twitter, Vine, and Instagram all started off as places to be yourself, but as they became more mainstream and their communities developed behavioral norms, the output became more crafted and refined. Users flooded in and optimized for what worked best on each platform. Blogs became more newsy and less personal, Flickr shifted toward professional-style photography, Vine got funnier, and Twitter’s users turned toward carefully crafted cultural commentary and link sharing. Editing worked its way in between the making and sharing steps. In 2013, Mat Honan wrote of Vine:

It built a ground up culture that feels loose, informal, and — frankly — really fucking weird. Moreover, most of what you see there feels very of-the-moment. Sure, there’s plenty of artistry that goes into making six second loops, and there are volumes of videos with high production values. But far more common are Vines that serve as windows into what people are doing right now.

Sounds familiar, right? I’m almost positive that when Instagram was first blowing up, similar things were written about it in comparison to Flickr. Now, as Wortham notes, Instagram is largely a place to put your heavily curated best foot forward. But scroll back through time on anyone’s Instagram and the photos get more personal and in-the-moment. Even Alice Gao’s immaculately crafted feed gets causal if you go back far enough.

Although more than a year older than Vine and fewer than two years younger than Instagram, Snapchat is a relatively young service that the mainstream is still discovering. It’ll be interesting to see if it can keep its be-yourself vibe or if users tending toward carefully constructing their output is just something that happens as a platform matures.

Buzzfeed’s Ben Rosen recently got a lesson from his 13-year-old sister Brooke about how she and her friends use Snapchat. Some highlights:

I would watch in awe as she flipped through her snaps, opening and responding to each one in less than a second with a quick selfie face. She answered all 40 of her friends’ snaps in under a minute.

I assume this is a slight exaggeration, but even 40 replies in 2 minutes is an insane pace.

BROOKE: My new account? About a month and a half.

ME: New account?

BROOKE: Yeah, I didn’t like my old name, so I made a new account.

Fluid identity, check. I have had the same email address and username on any and all new services since the 90s.

BROOKE: No conversations…it’s mostly selfies. Depending on the person, the selfie changes. Like, if it’s your best friend, you make a gross face, but if it’s someone you like or don’t know very well, it’s more regular.

ME: I’ve seen how fast you do these responses… How are you able to take in all that information so quickly?

BROOKE: I don’t really see what they send. I tap through so fast. It’s rapid fire.

Response as message. Virtual eye contact. Like liking or faving. This reminds me of Matt Webb’s Glancing project. I’m ok, you’re ok. Virtual primate social grooming.

BROOKE: Yeah. This one girl I know uses 60 gigabytes [of cellular data] every month.

I use 60 Gb of data per year. If that. Do teens not know about wifi?

ME: How often are you on Snapchat?

BROOKE: On a day without school? There’s not a time when I’m not on it. I do it while I watch Netflix, I do it at dinner, and I do it when people around me are being awkward. That app is my life.

ME: What the hell is a NARP?

BROOKE: Nonathletic Regular Person. NARP.

I am looking forward to working for Brooke when she’s 24. She’s clearly going to be in charge.

BROOKE: If you want to take a screenshot without your friend knowing, turn on airplane mode, take the screenshot, log out of the app immediately, turn off airplane mode, and then load the app back up.

Up up down down left right left right B A.

Update: I’ve seen a few people saying that how Brooke and her friends use Snapchat is how adults should be or will be using social media in the future. I don’t think that’s right. How teens use Snapchat is how many teens use anything they are intensely interested in and/or keep them in contact with their friends. Adults probably cannot and will not use Snapchat like this. They have different priorities.1 Go read the Buzzfeed piece again…it’s all about social status, something 13-year-olds care about very much, perhaps more than anything. “That app is my life” is not an exaggeration or an over-dramatization.

Back in the day — and I’m talking about around the invention of farming and even further back — everyone you knew in the entire world was never more than a few hundred feet from you for more than a few days. Wheels, domesticated crops & animals, industrialization, cars, and airplanes made it so that people could live farther and farther apart from each other, which is weird for social animals like humans and particularly difficult for teenagers for whom that social connection is the most important thing in their lives.

Smartphones, Instagram, Snapchat, and generous data plans have closed that distance again in many ways…or more precisely, have made the distance less relevant. Interacting with 190 friends1 dozens or even hundreds of times a day probably feels a lot like being back in a hunter/gatherer band, socially speaking. Thanks to these magic pocket-sized rectangles, everyone you know in the world is never more than a few seconds away for more than a few hours.

Photographer Clayton Cubitt and Rex Sorgatz have both written essays about how photography is becoming something more than just standing in front of something and snapping a photo of it with a camera. Here’s Cubitt’s On the Constant Moment.

So the Decisive Moment itself was merely a form of performance art that the limits of technology forced photographers to engage in. One photographer. One lens. One camera. One angle. One moment. Once you miss it, it is gone forever. Future generations will lament all the decisive moments we lost to these limitations, just as we lament the absence of photographs from pre-photographic eras. But these limitations (the missed moments) were never central to what makes photography an art (the curation of time,) and as the evolution of technology created them, so too is it on the verge of liberating us from them.

And Sorgatz’s The Case of the Trombone and the Mysterious Disappearing Camera.

Photography was once an act of intent, the pushing of a button to record a moment. But photography is becoming an accident, the curatorial attention given to captured images.

Slightly different takes, but both are sniffing around the same issue: photography not as capturing a moment in realtime but sometime later, during the editing process. As I wrote a few years ago riffing on a Megan Fox photo shoot, I side more with Cubitt’s take:

As resolution rises & prices fall on video cameras and hard drive space, memory, and video editing capabilities increase on PCs, I suspect that in 5-10 years, photography will largely involve pointing video cameras at things and finding the best images in the editing phase. Professional photographers already take hundreds or thousands of shots during the course of a shoot like this, so it’s not such a huge shift for them. The photographer’s exact set of duties has always been malleable; the recent shift from film processing in the darkroom to the digital darkroom is only the most recent example.

What’s interesting about the hot video/photo mobile apps of the moment, Vine, Instagram, and Snapchat, is that, if you believe what Cubitt and Sorgatz are saying, they follow the more outdated definition of photography. You hold the camera in front of something, take a video or photo of that moment, and post it. If you missed it, it’s gone forever. What if these apps worked the other way around: you “take” the photo or video from footage previously (or even constantly) gathered by your phone?

To post something to Instagram, you have the app take 100 photos in 10-15 seconds and then select your photo by scrubbing through them to find the best moment. Same with Snapchat. Vine would work similarly…your phone takes 20-30 seconds of video and you use Vine’s already simple editing process to select your perfect six seconds. This is similar to one of my favorite technology-driven techniques from the past few years:

In order to get the jaw-dropping slow-motion footage of great white sharks jumping out of the ocean, the filmmakers for Planet Earth used a high-speed camera with continuous buffering…that is, the camera only kept a few seconds of video at a time and dumped the rest. When the shark jumped, the cameraman would push a button to save the buffer.

Only an after-the-fact camera is able to capture moments like great whites jumping out of the water:

And it would make it much easier to capture moments like your kid’s first steps, a friend’s quick smile, or a skateboarder’s ollie. I suspect that once somebody makes an easy-to-use and popular app that works this way, it will be difficult to go back to doing it the old way.

Stay Connected