kottke.org posts about The State WeÕre In

OK, Kottke faithful: this is it—the last of my interviews on The State We’re In. I know you’ve all come to know and love Jason’s short, link-y goodness (so do I) & am happy to say it returns tomorrow. Meantime, I can’t think of a better way to cap off this week’s talks than with Steven Berlin Johnson. Author of two of my favorite books, Emergence and The Ghost Map, Steven also heads up one of the more interesting social networking sites, outside.in. He spent some time this week exchanging ideas on the Web’s various geographies and the different ways we navigate both the physical and mental worlds we inhabit.

JT: Outside.in is a great idea—I love the kind of Jane Jacobs/crowded sidewalks thing you’re striving for—or seem to be: how is it working out? Have you been surprised by anything? Any new ideas?

SBJ: It has been really fun and rewarding. I had seriously resisted the idea of starting a new company, because my lifestyle as a writer for the past five or six years had been pretty amazing. But it’s just such an interesting problem that we’re trying to solve at outside.in, and it’s such an interesting time to be trying to solve it—so I ultimately couldn’t help myself. In a way there are a lot of parallels to the timing of the first two web sites that I helped build—trying to build an online magazine (FEED) in 1995, or a community-authored news site (Plastic) in 2000 is quite a bit like trying to build out the geographic web in 2007.

One of the big surprises has to do with the long tail of geography. When we originally conceived of the site, we thought the tail was all about neighborhoods—that was the geographic niche that big media had traditionally ignored in favor of cities and greater metro areas. But it turns out the tail is even longer: a huge amount of our traffic goes to our place pages, where you can see all the discussion from around the web about a specific public school, or park, or restaurant, or real estate development. So we’ve started adjusting the UI for the site to reflect that focus; the new city front door has a “Places” tab that lets you see the most talked about places in your community.

But I think the most surprising thing about it is how hard it is to convince people of the general importance of geo-tagging pages. I’ve just written a little essay—called “The Pothole Paradox“—to coincide with the new version we’re launching this week, and one of the things that I talk about is the fact that the Web itself was made possible by standardizing the virtual location of pages. And in many ways, what made blogging so valuable was that you had standardized time stamps for pages as well. So we had virtual space and actual time, but not actual space. But it turns out there are amazing things that can be done if the geographic location of pages (the location they’re describing, not where their servers are located) is machine-readable. Flickr showed this with photos, of course, and we’re trying to make the case for it as well.

JT: One thing I wonder about is whether or not you could (or, even so, should) consider other kinds of geographies: of the mind, for instance. I live in Minneapolis, but as a writer I spend a week to a month every year in New York. My daily paper—to the extent that this notion even makes sense anymore: but until very recently it was an actual paper—is The New York Times. Isn’t one of the great things about the Web—and specifically things like blogs and social networking sites—that we have the tools to build dense communities that map to more than just the physical geography of our lives? And these geographies interact in interesting ways (consider the richness of Thoreau’s remark: “I have traveled a great deal in Concord.”): are we bound to live in a world in which these maps—and their attendant communities—are disconnected?

SBJ: I think you’re absolutely right. And yet the fact that the Web creates a new kind of semantic or social geography untethered to physical space doesn’t mean that the old kind of geography disappears. 99% of the Web 2.0 companies that have launched over the past five years have been, in effect, pursuing those kinds of new associations that you describe, but there hasn’t been nearly as much focus on the possibility of using the Web to enhance physical geography. So we’re trying to correct that imbalance. If everyone was doing hyperlocal, and no one was doing, say, social networks, I’d probably start a social network site.

What we’re really grappling with at outside.in is the fact that we built the site around a very specific ideal-case geography: Brooklyn. In other words, it’s a site that works really, really well in communities where you find high population density, many local bloggers, intense gentrification and development debates, and clearly-defined neighborhoods. But it turns out the rest of the country (much less the world) doesn’t always look like Brooklyn. So that’s one of the things we’ve been tweaking in terms of the way that the database is structured.

JT: In an interview with Jason B. Jones in Pop Matters last year, the two of you talked quite a bit about the Long Zoom as a kind of guiding principle of your books, specifically in my two favorites: Emergence and The Ghost Map. In the latter, the zoom between the physical and mental map of the world—the long zoom from our senses and surroundings to our greater ideas about those things—zoomed up quite naturally into error & disaster. Then John Snow recalibrated things, created a new, different path along which to zoom, and virtually eliminated cholera from London. You and Jason referenced the great Eames documentary, Powers of Ten, in this regard: but isn’t this metaphor broken—or at least inexact? We’re not really just going up and down—but more like traversing an n-dimensional graph. Outside.in gives us a way of moving in certain directions—but I wonder whether you have any thoughts on how the blogosphere, the ways in which it creates large numbers of short paths, helps us navigate the world? Or does it, as the complainers say, just muck it up?

SBJ: One of the great things that Jane Jacobs wrote about in Life and Death of the Great American Cities is the design principle of favoring short blocks over longer ones—the crooked streets of the Village versus the big avenues of Chelsea—because short blocks diversify the flow of pedestrian traffic. In an avenue system, everyone feeds onto the big streets, and you have insanely overcrowded streets and then side streets that are deserted (which leads to storefront real estate that only the big chains can afford, and real estate that no one wants because there’s not enough foot traffic). In a short block model, the streets tend to gravitate towards that middle zone where there are always some people on them, but not too many.

I’ve always thought that the blogosphere can be thought of as a kind of small blocks model for the Web, whereas the original portal idea was much more of a big avenues model. Yes, there are some increasing returns effects that lead to some A-list bloggers having millions of visitors, and yes, there is a long tail of bloggers who have almost no traffic. But the healthiest part of the curve is what Dave Sifry once called “the big butt”—the middle zone between the head and tail of the Power Law distribution, all those sites with 1000 to 100,000 readers. That’s the part of the blogosphere that I think is really cause for celebration, because something like that just didn’t exist before on that scale. And as Yochai—who of course is very smart about all this—points out: those mid-list sites also communicate up the chain to the A-listers, who can broadcast out the interesting developments in the mid-list so that those stories enter a broader public dialogue. Maybe the new slogan is, “In the future, everyone will be famous for 15 Digg links.”

Your “n-dimensional graph” is exactly right, and it’s exactly that shape that makes the “death of public space” or “Daily Me” argument so silly. There are plenty things to complain about in the kinds of communication that the Internet fosters (think about the spam alone), but the idea that this environment is somehow encouraging too much filtering, too much echo-chamber insularity, is a fundamental misreading of the medium.

JT: Finally, I want to stump for story for a minute—but then raise some questions about their role & interaction with the Web and blogs and the ubiquity/inexpense of media produciton. A part of me thinks that every additional word I say about something I publish diminishes it in some way: I write a book with (very nearly) exactly the right combination and number of words to mean what I say. And then several other parts of me chime in to say, “But you know that’s not the whole story!” or “Don’t you wish you could say ‘X’ now—after it’s too late to include it in the book?” You point, for instance, to Ralph Frerichs’ John Snow site at the end of The Ghost Map and mention Tufte’s work and there are a host of reproductions of the map available (including this one, in Flash). I also think that, by now, we all know that authorial intention isn’t all it’s cracked up to be—and yet, it’s not trivial. Given that just about everything is connected to everything else now, what is the role of the discrete story?

SBJ: I’m kind of a traditionalist when it comes to the book form, particularly the writing process. The book is fundamentally a one-to-one form, in the sense that 99% of the time, you’re talking directly as a single author to a single reader, and the whole interaction is about this very intimate exchange (though of course it’s a very one-way exchange). No doubt you end up having many different readers if your books are successful, but the actual experience of the form keeps returning to that direct encounter between two individual minds. I love that about books, and I’m probably happiest and most at home when I’m in the middle of writing one. And so that part of the constraint I really embrace; I almost never discuss the book I’m currently writing on my blog, for instance.

But at the same time, I love all these new forms that are emerging where the relationships between authors and readers are far more complicated and multi-dimensional, which also causes the text itself to blur around the edges. When you look at something like TechMeme, it’s about as far as you can get from that one-to-one exchange. And that’s great. Or BoingBoing—I mean, those guys might have had only 25 phone calls, as Cory said, but there’s an incredible group jam going on there that’s entirely distinct from the much more private, interior space of book writing.

For me, the blog is where the edges of the book form blur, and blur in a really nice way—after the book comes out. I can’t imagine publishing a book now without having the blog to promote, respond, re-evaluate, extend, connect—even retract! It’s not quite as impossible to imagine as writing without Google (which seems like writing a book on a typewriter to me now) but it’s close.

Jane Ciabattari is a fiction writer, book critic and widely published journalist. She’s on the board of the National Book Critics Circle (for which she is a co-blogger on their Critical Mass blog) and is Vice President of the Overseas Press Club. Since it seems to me (a blogger, author, and NBCC member critic) that one of the great opportunities for blogs is to provide a wider audience—and greater number of voices—for criticism, I was thrilled that she took time out of a busy schedule to talk about blogs and the future of criticism.

I wrap up my week here at kottke.org tomorrow with an interview with Steven Berlin Johnson.

JT: What was the motivation behind starting the NBCC Critical Mass blog? It’s one of my essential reads. I also wonder: is there any irony in its excellence, given the rancor against bloggers that has come from newspaper critics this summer? Or some of the return-fire directed by bloggers?

JC: The idea of developing a literary blog for the National Book Critics Circle seemed natural. When it was launched in April of 2006, it provided an instant online community for those of us who are NBCC members and who are passionate about books and book criticism and book culture. It created a quick way for us to communicate with members, to address issues of note to us all, and to provide an ongoing “snapshot” of contemporary book culture by including interviews and lists of what authors and member critics in various parts of the world are reading.

It’s also allowed us to launch a number of ongoing series: In Retrospect, in which today’s critics re-visit all the finalists and winners of NBCC awards from the past 33 years; “Thinking About New Orleans,” about New Orleans writers displaced or disoriented by Katrina and its aftermath; and, of course, the NBCC Campaign to Save Book Reviewing.

The irony as I see it is that a number of newspaper reporters and literary bloggers implied that the NBCC was against blogging and in favor of print book reviews. This is an unfortunate and reductive—and unnecessarily divisive—perspective that I don’t share. The NBCC is in favor of a diversity of book reviewing forms. The content is not an issue. The forms merge, morph, transform. One evaporates here, another pops up there. This is part of a vibrant book culture that continues despite the shifts in book reviewing in recent months and years.

JT: I wonder what the role blogs play best in the book world? There’s a big difference between book discussion or gossip and book criticism—blogs do a great job of the former, but not such a great one at the latter: does it matter? Of course, a lot of lit-bloggers have gotten the attention of the newspapers and become critics in their own right: Mark Sarvas and Maud Newton come to mind. Is this going to be a kind of permanent divide—blogs for book culture and newspapers (or their Web sites) for substantive reviews?

JC: I think of this as a moment of pause, a transition, an exciting time in which to watch what the reaction will be to the changes in the newspaper world and elsewhere—as well as the growing familiarity with the gatekeepers of the blogosphere. I think we’re beginning to see some creative solutions evolve.

The NBCC membership includes not just print and broadcast reviewers, but literary bloggers like Mark Sarvas and Jessa Crispin and Lizzie Skurnick who are proprietors of literary websites. We have had two NBCC board members who have founded and hosted literary blogs that are now more than five years old and many literary bloggers are now reviewing for print publications or providing content for the online parts of newspaper book sections. The best of those, the Maud Newtons and Lizzie Skurnicks and others, are making that transition with no trouble.

I have written for The Guardian’s blog, and I read it regularly. The combination of the print edition of a newspaper’s book section and the expanded online editions, with blogs plus comments, additional reviews, seems like a natural thing and this format is building in this country—we now have multimedia book sections in The New York Times, the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune, and others.

I would guess that within a few years the literary blogosphere will have been mostly digested by the websites of the larger newspapers, that the Hearsts and Murdochs and Newhouses of the world, who have the capital and the business savvy to figure out how to attract the most talented, will become the dominant forces online. Online readers are increasingly women, increasingly people over 40, and polls indicate that they will be most likely to trust the gatekeepers the know—i.e., newspapers with familiar names—to give them online news.

I have been listening to the dreams for broadband since before the dot.com collapse, and it is indeed exciting to have the speed and facility of highspeed Internet available for authors, critics, researchers, and students. But I am reminded by every passing thunderstorm and summer brownout or blackout that none of this works without a healthy electrical grid. And that some of the mountains and rural areas where I spend time, and some of the readers I know, people who want their children to be readers, are not able to afford or even obtain highspeed connections where they live: newspaper coverage of books is still very important to them.

We launched the NBCC Campaign to Save Book Reviewing in conjunction with the shift of the Los Angeles Times book review from a stand-alone section to a section combined with Opinion (and the shift of some content online) and the elimination of the book editor’s position at the Atlanta Journal and Constitution, the largest newspaper in the South and the literary home of many of the country’s great writers. There were lots of other newspapers going through transitions in books and arts coverage, too—as well as the fact that academic libraries began eliminating print versions of the literary quarterlies that are the lifeblood of American literary fiction and poetry in favor of electronic databases. It seemed a tipping point, and time for a conversation about the issue—one that we have been conducting both on the blog and through public panels.

What does the shrinking of print newspaper book coverage mean for authors? Novelist Lee Smith offered her perspective from North Carolina on the NBCC blog, noting that she was troubled when her latest book, On Agate Hill, came out last fall: “It was getting pretty good reviews, though fewer reviews. Then I got one really unfavorable review by an influential critic in a major city, which was reprinted in about 20 other newspapers that had cut back on their local coverage and were using syndicated book reviews. I was talking to my husband about all those bad reviews the book got, this was my own negative experience, my feeling about it, and he said, Wait a minute, it got ONE bad review, carried in 20 papers.”

Bottom line: It’s not great if newspapers are syndicating one review and spreading it around; it’s better if newspapers expand the number of books they review by doing it online. The small press books, the independent books, will always be in need of champions. At Critical Mass, I have started a series called Preview 2008, with a specific focus on small-press books that lack the promotional budgets of the larger publishers.

JT: Anyone who’s worked at a newspaper knows how discomfiting it can be to see all the books that go unreviewed—that’s something you don’t hear a lot about: questions about who gets reviewed, why, and so on. The world’s bloggers may not be the best critics (though many are wickedly smart): but from the writers’ and readers’ and publishers’ perpectives, wouldn’t we all be better off if publishers sent 100-200 galleys of every book to the 100-200 most-prominent bloggers in the circles of interest most likely to buy or enjoy a given book? It seems like there’s a lot of inefficiency in the marketplace—and a place for a burgeoning trend here, doesn’t it?

JC: As much as it makes sense to send galleys to prominent bloggers, I think you have to think first about readers; ultimately, the majority of online readers still go to newspaper websites for their information. The evolution of newspapers continues. Beginning in September, the Audit Bureau of Circulation will combine print and online circulation of newspapers, which I believe will show a better picture of what has been going on in the United States. In July, for instance, 59.6 million people visited newspaper websites, a 9 percent increase over the same period a year ago. Nearly eight in ten adults read a print or online newspaper each week. As I’ve noted, many of the best literary bloggers are writing for newspaper book review sections and online websites. Readers are also going to communities like Readerville.com, which is a terrific website for readers and writers. Internet space may be infinite, but readers are pressed for time: I suspect quality will out, online or off.

JT: Finally, I think one thing the blogosphere does extraordinarily well is broaden the base of discussion—while still preserving the idea of the cream rising to the top. It’s just that, on the Web, there are a lot more buckets. As critics and writers, should it matter to us that the “center doesn’t hold?” Is there really anything wrong with there being a large number of different centers—each connected to each, each permeable and in constant flux?

JC: I interviewed Yochai Benkler a number of years ago in a piece for New York Lawyer that predicted that he would be one of the attorneys under forty who would influence the 21st century. I am pleased to see he continues to break new ground, and I found his book fascinating. I see nothing wrong with a large number of different centers, interconnected, permeable, in constant flux: that is the nature of the Internet. Having reported from Cuba, where the flow of information is censored, and China, where the Internet is censored but only partially obstructed because of the various ways one can get around the firewalls, I would not want to see that constant flux impeded. But I also spend enough time in rural areas where broadband Internet connections are either unavailable or too expensive that I’m only too aware that printing is still an important technology—and that it’s important to maintain it for those who read newspaper book reviews, whether at home or in local libraries; whether from desire or necessity. To ignore the needs of this part of the American population would be to undermine our democratic roots—literacy is at the base of an educated citizenry.

That said, for me the ideal is a multi-media approach, with a maximum of choices. A world in which I can listen to public radio, read various newspapers online or in print, watch the BBC and Colbert and John Stewart, catch up with my favorite literary bloggers (chosen because I’ve come to know and love their sensibilities), and continue to have what the MacDowell Colony’s 100th anniversary slogan calls “the freedom to create.”

I can’t think of anyone better suited to answering questions about the state of culture in the Age of the Blog than Cory Doctorow. Whether it’s running Boing Boing, writing (and giving away—while still profiting from—his novels and short-story collections), or speaking out for our electronic rights, Cory is a ubiquitous presence on every vector of this discussion. I caught up with him by phone at his London flat.

JT: Let’s talk about the ‘Pixel-Stained Technopeasantry’ discussion in the sci-fi community this summer. I thought it was sort of ironic that someone like Hendrix—a sci-fi writer— would resign over the use of technology—

CD: He didn’t resign: He just didn’t run again.

JT: —Or just didn’t run again. OK, so that was just his parting shot? There was another line he used, too—what was it? Webscabs. What’s the deal with giving away your stuff for free?

CD: There are three reasons why it makes sense to give away books online. The first is that publishing has always been in this kind of churn and flux—who gets published, how they get paid, what the economic structure is of the publishers, where the publishers are, all of that stuff has changed all of the time. And it’s just hubris that makes us think that this particular change—the computer change—is the one that’s going to destroy publishing and that it must be prevented at all costs. We’ll adapt. If we need to adapt, we’ll adapt. And today, the way that we adapt is by giving away e-books and selling p-books.

So that’s the economic reason. But then there is the artistic reason: we live in a century in which copying is only going to get easier. It’s the 21st century, there’s not going to be a year in which it’s harder to copy than this year; there’s not going to be a day in which it’s harder to copy than this day; from now on. Right? If copying gets harder, it’s because of a nuclear holocaust. There’s nothing else that’s going to make copying harder from now on. And so, if your business model and your aesthetic effect in your literature and your work is intended not to be copied, you’re fundamentally not making art for the 21st century. It might be quaint, it might be interesting, but it’s not particularly contemporary to produce art that demands these constraints from a bygone era. You might as well be writing 15-hour Ring Cycle knock-offs and hoping that they’ll be performed at the local opera. I mean, yes, there’s a tiny market for that, but it’s hardly what you’d call contemporary art.

So that’s the artistic reason. Finally, there’s the ethical reason. And the ethical reason is that the alternative is that we chide, criminalize, sue, damn our readers for doing what readers have always done, which is sharing books they love—only now they’re doing it electronically. You know, there’s no solution that arises from telling people to stop using computers in the way that computers were intended to be used. They’re copying machines. So telling the audience for art, telling 70 million American file-sharers that they’re all crooks, and none of them have the right to due process, none of them have the right to privacy, we need to wire-tap all of them, we need to shut down their network connections without notice in order to preserve the anti-copying business model: that’s a deeply unethical position. It puts us in a world in which we are criminalizing average people for participating in their culture.

JT: What was it that the philosopher J. L. Austin said? “Things are getting meta and meta all the time.” Almost of necessity, because if you don’t have meta-level discussions and filters (and we have MetaFilter), bloggers like kottke and boing boing—in academia I’m going to Arts & Letters Daily and Crooked Timber—you’d never be able to fire through all the cool things to which we now have access. By making use of a small number of editorial nodes, we can cover lot more of the network. But it’s more interesting than simple efficiencies, isn’t it? I interviewed Douglas Wolk earlier this week and he said something pretty profound: “Each blogger is a gravitational center, great or small, but there’s no sun they’re all orbiting around.” Yochai Benkler, too, with his idea of the bow-tie model, talks about how, because of shallow paths and the small world effects of the Internet, this idea that there are these multiple centers of gravity mean it’s not like there’s one giant “culture” that’s omnipresent, along which there’s this Power Law distribution that drowns everything out. Instead, there are tons of these smaller gravitational centers, each with their own orbits; each with their own authors, interests, inclinations to reach outward and bring other things in… it pretty well vanquishes certain notions of centrality, the cry that says, “Holy shit: I’m not in The New York Times! Nobody in our culture will ever find me!” That’s nonsense. You can have an audience of millions, maybe none of whom have ever read The New York Times.

CD: You just recapitulated in reverse the panic of Andrew Keen. What Andrew Keen has got his pants in such a ferocious knot about is that we are losing our “culture.” Basically, if you unpack his arguments they come down to this: He thinks The New York Times did a pretty good job of figuring out what was good and he doesn’t like the idea that they’re not the only way of doing it and that it’s getting harder to figure out who to listen to and media literacy is getting harder and that means bad stuff is going to become important and that wouldn’t have happened if only the wise, bearded, white-robed figures at The New York Times had been allowed to continue to dominate our culture. That’s really where he’s coming from at the end of the day.

JT: In fairness to the Times, they not only pay well, but they do a good job of reaching out—to their guest-bloggers, for instance. The Guardian does, too.

CD: Yes, they do and they do. But as a writer, actually having all these different venues in which my work can appear has actually turned out to be better and not worse. So for one thing, the free online distribution of my work has created new opportunities—it’s like dandelion seeds blowing around that find all the cracks in the sidewalk that I never would have been able to find just by walking around and planting them. One of my favorite reprints was one I sold to a magazine who’d found the text in the word-salad at the bottom of a spam e-mail. So even the spammers are helping me.

JT: That’s really funny. In another interview I did, the one with Ted Genoways, he said something that I hope a lot of people pick up on, because I think it’s incredibly important to this discussion. What Ted said was that, after doing their big South America in the 21st Century issue—for which they got a lot of good press: authors on NPR, segments on PBS—they got a small amount of traffic from mainstream media. But then Jason posted a small link and they got 25,000 visits that week from kottke.org.

CD: I think the most important thing about that anecdote isn’t the amount of influence that kottke.org wields, although that’s an interesting component of it, but how cheap it is to become kottke.org—to maintain Kottke Enterprises, Ltd. It’s so cheap it’s the rounding error in the coffee budget of the smallest department of one of the main publishing conglomerates. That’s all it costs Jason to run his website.

Boing Boing, and I’m not just talking cash costs—but also organizational costs, the Coasian costs, of doing this are so low. Boing Boing, for the first five years, we never had a physical meeting. We had never all been in the same room until we had been in business for five years. We had 25 phone calls in the entire history of the business.

So, a lot of bloggers can wield tremendous influence, and become disruptive forces in the media marketplace, very cheaply. If you have someone who’s enthusiastic and compelling and that person is very close to the purchase decision—you know, it probably drops off with the square of the distance, right? So you can have a person like Oprah, who’s so compelling that the fact that she’s extremely distant from a book she’s pitching is not wildly important, because she sends such a strong signal that even though it attenuates quickly that signal is still very strong. Who was the President who popularized the James Bond novels? Kennedy? He mentioned it and he turned James Bond into a phenomenon. The corollary of this is that a weak signal heard close in is also an extremely powerful way to sell books. So, we’ve historically relied on strong signals at great distances, but the other way to do this is weak signals close in. And we have new ways to get close: with things like Amazon links, the signals don’t have to be very strong at all.

This is also an essential component of the value of the free electronic copy. The microcosm for that is “here’s a free electronic copy… talk about it in IRC with two other people.” And that gets you the same thing. You don’t even have to send out a physical review copy & those people, if they like your book, will start sending the book to their friends.

JT: It all sounds good—but let me go on record as, in the broadest range of things, a middling copyright defender. But I loved Tim Wu’s piece in Slate. Did you read that? On how selective enforcement of copyright shows just how broken copyright law is? But—let’s get to the complications of sending out free work. If somebody started passing off your work as their own, you would not be happy.

CD: I went to elementary school with Tim. It’s a small and funny world that the two of us would end up as Lessig’s proteges. But to your question: that’s not copyright, that’s fraud. That’s plagiarism.

JT: OK, if a publisher started selling a book written by “Frank Smith,” but that contained only your words—isn’t that a danger to giving your stuff away electronically, for free?

CD: So, let’s pick the issues right. Let’s first of all say that fraud or plagiarism is bad for a number of different reasons—not all of them having to do with the writer, some of them having to do with the reader. Readers deserve to know that the thing that they buy has been accurately labeled. I also wouldn’t approve if someone sold Coke in a Pepsi can. Not because I particularly like either beverage, but I think fraud is wrong. So that’s the first question. The second question is, “How would I feel if a corporation misappropriated the fruits of my labor and profited by it without my permission?” And that’s a meatier question, but when you conflate the two you just confuse the issue.

I guess it depends on the kind of profit and how they’re profiting by it. So, I don’t get upset if a carpenter sells a bookcase to someone and makes money because that person needs somewhere to put my book. Even though that carpenter is benefiting from my labor. So I think reasonable people can agree that there are categories of use that you have no right to recoup from. And I think that, for example, search results fall into that category. You know, the fact that Amazon or Google want to show quotes from your book alongside search results for people who are trying to find out which books contain which string, I think it’s just crazy to say that you deserve to be compensated for that—even if they could figure out a way to make money off of it. Indexing books is just not in the realm of things that we deserve to get compensated for, any more than library lending is.

And I know that in Europe they do have a library right, and you actually do get compensated for library use. I actually think that’s kind of gross. I don’t think that’s good public policy. If we want to subsidize writers with public money, don’t take it out of the budget of the library. What a disaster for public policy, for good stewardship, to take money out the hands of the public libraries. What a disaster that writers have actually endorsed this plan.

So that leaves us with a narrower category of uses, which are the uses that are neither cultural nor in the realm of accepted, normal, reasonable exceptions to one’s copyright: where it’s a direct infringement and there I do in fact object to a commercial publisher reproducing my work without giving me money for it, holus-bolus, in a way that is not consistent with fair use and historical exceptions to copyright.

But that’s not the same thing as objecting when a reader does it. I think that we’ve always had a different set of rules for what non-commercial actors do than for what commercial actors do. What commercial users of a work do is industrial—that’s copyright; what non-commercial users of a work do is just culture, and culture and copyright have never had the same rules, although according to the law books they do. But the costs of enforcing them culturally—against the person who sings in the shower—those enforcement costs are so high that historically we’ve treated that activity as though it weren’t an infringement, when in some meaningful sense it is. So, the fact that the Internet makes it possible to enforce against certain cultural users I don’t think means that we should enforce against cultural users, or start pretending that schoolchildren should be taught copyright so they can understand it better and not violate it. If things that schoolchildren do in the course of being schoolchildren violate copyright, the problem is with copyright—not with the schoolchildren.

I think it’s safe to say that this will be the chewiest of my interviews this week—and also the most important. Lawrence Lessig’s Code 2.0 was good, but Yochai Benkler’s The Wealth of Networks may well be looked on in the future as highly as John Rawls’ A Theory of Justice is today. If you want a deep, yet readable, look into the issues of how the ‘Net affects cultural production, social justice, and economic development, The Wealth of Networks is the best discussion available. Yochai Benkler is the Berkman Professor of Entrepreneurial Legal Studies at Harvard, and faculty co-director of the Berkman Center for Internet and Society. I’m thrilled that he took the time to answer a few questions for me this week.

JT: I first learned about your book over at the Crooked Timber blog—and thought the discussion of your book there was of exceptionally high quality. Moreover, your book has been far more often mentioned than reviewed in the press. Which poses a kind of serial question: When traditional journalists (I’m thinking specifically of Richard Schickel’s rant in the L.A. Times this summer) bemoan the rise of blog culture, do they know what they’re talking about? Have they looked? From your side: How did the Crooked Timber—or other blog receptions—compare to traditional media receptions?

YB: I thought the discussion on Crooked Timber was in fact excellent, as good a discussion as you would get in a thoughtful seminar, whether academic or whenever you get a collection of thoughtful people in a book club. There should be nothing surprising about this, any more than there should be anything surprising about there being blogs that are utter nonsense.

The critical shift represented by the networked information economy is that on the order of a billion people on the planet have the physical capacity to produce and communicate information, knowledge, and culture. This means, in the case of writing, millions or tens of millions of people, rather than a few thousand, get to write in ways that are publicly visible. Of necessity, there will be a wide range.

The probability that any newspaper, however well-heeled, will be able to put together the kind of legal analytic brainpower that my friend Jack Balkin has put together on his blog, Balkinization, is zero. They can’t afford it. On the other hand, even the Weekly World News is tame and mainstream by comparison to the quirkiness or plain stupidity some people can exhibit. The range is simply larger. That’s what it means to have a truly diverse public sphere.

If you want to find evidence of nonsense, as of course it is important to people whose sense of self-worth depends on the special role traditional mass media play in the public sphere, you will easily find it. If you want to find the opposite, that too is simple. What’s left is to wait and see over time whether one overwhelms the other. As I wrote in the book, I do not think we are intellectual lemmings. I don’t think we jump over the abyss of drivel, but rather that in this environment of plenty we learn to develop our own sense of which is which, and where to find what. Perfect information about all the good things, we won’t have. But we don’t have it now either. Instead we have new patterns of linking, filtering, recommendation, that allow us to do reasonably well in navigating a much more diverse and interesting information environment than mass media was able to deliver.

JT: Harvard University Press published your book—but you’re also giving it away free on the Web. Which is great, except: it’s 527 PDF pages long, which makes it much more expensive (even double-sided!) to print at home than it is to buy the actual book. What does this tell us about some of the complications inherent in statements like “information wants to be free,” or about things like market efficiency and the marginal costs of distributing information? After all, a book is not just the information inside, but a produced technology—and, often times, a beloved artifact.

YB: It was Yale University Press. Harvard was not willing to release the book under a Creative Commons license, which was the tie-breaker for me between the two presses. As for the online free availability, I think that the facts you describe are part of what gives publishers freedom to experiment with the medium now. The display technology is still sufficiently far behind paper and print, that it’ll be a good few years before free online availability will translate into online delivery in the mode of music or, now, video.

But for me what was more important than simply the freedom to download, was the freedom to do things with the book. That’s why I held out for licensing the book under a CC noncommercial sharealike license. The fact that people were able to take the book and convert it into other formats, including making readings of some portions; that some people began to translate portions of the book; these were the reasons that mattered.

I think for academic books in particular, where people may want to assign short portions, or to have students respond to materials, the flexible, permissive book format offers a good complimentary platform. Similarly, in terms of the economics of academic publication, I think the press found that they did much better than usual with this book, partly, at least, because many more people got partial exposure to it online, and then bought it. But I don’t think that this is the long-term strategy for academic presses. Because ultimately the display technology will catch up. What is the right path for academic presses is to use this transition period to learn how to make online books and book sites into powerful learning platforms, and to use those capabilities to reorient the universities from the trend to treating the presses as self-sustained centers, back to a time when the presses were part of what universities needed to subsidize from their main teaching role—as part of their effort to disseminate the knowledge they produce.

JT: I was disappointed that you didn’t mention Lewis Hyde’s The Gift in your own book. Do you know it? I ask because I thought it would be too easy to simply ask about the “Carr-Benkler Wager,” which, if I’m stating it correctly, concerns the question about whether or not the top Web sites (blogs, Flickr, Wikipedia, YouTube, et. al.) would all be run by professionals in the future. Nicholas Carr says “Yes,” and you say “No.” The problem I have with this is way of framing the question is that it seems to misunderstand why people create—even professionals! Do you take this bet seriously? Regardless of whether you do, isn’t the matter of all production—whether it’s the manufacture of goods, delivery of services, scientific research, artistic creation, or whatever—a lot more complicated than the matter of getting paid for it?

YB: I agree that production, in particular intellectual production, is much more complex than a matter of getting paid for it. I spent a lot of the book, both in Part I on the economics of commons-based individual and peer production, and in Part II in trying to understand the production of the public sphere, both political and cultural, as well as how the commons relate to autonomy and peer production applies to justice and development, trying to work through the complexities of information and knowledge production in different industries, and of different types. My basic claim is that people are diversely motivated, and that large-scale collaboration platforms, with permeable boundaries, freedom and capacity of action, on materials modularized for diversely-sized contributions, allow for the pooling of a diverse range of human talent, insight, experience, and wisdom—much more so than was feasible in more slow-moving organizations, and more richly diverse than a purely price-based system can characterize and monetize.

That the “Carr-Benkler Wager” got boiled down to a soundbite is not my fault. Even Carr’s original critique was twofold: partly about whether there was simply inefficient pricing, and partly about whether we see a re-emergence of hierarchy. I answered only half his challenge, in a short reply post to his original. This was then amplified and simplified. Not necessarily the best example of where the ‘Net improves the quality of information.

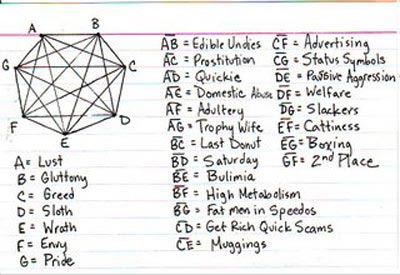

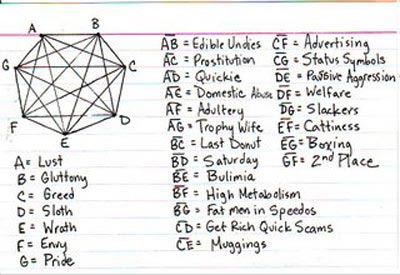

JT: Then again… we all like to get paid, don’t we? Whether the pay is in attention, respect, money, what have you—it can be hard to come by: even if you’re just out to Homestead the Noosphere, there are millions of others trying to do the same thing. Blogs do seem to be a way to break through the near-monopolies of mass media, but then there’s this question of the Power Law distribution. In The Wealth of Networks, you propose that the Power Law doesn’t perfectly apply, and talk about how “small world” effects and “shallow paths” actually make the Web and blogs—just as subject to hierarchy as any other network—more porous and democratic than traditional media. Jessica Hagy, to whom I talked earlier this week, is a good example of breaking through—and Douglas Wolk’s idea of blogs as individual gravitational centers with no sun around which to orbit will stick with me for a while. Can you talk briefly about this “bow-tie effect?”

YB: The basic problem as to which I applied the work on link distribution was the claim that discourse was fragmented, and therefore unable to support a public sphere. That is, of course, related to the first question about quality and diversity of information on the ‘Net. The basic insight we get from the empirical work that has been done on link distribution is that we do not randomly bump around from one irrelevant site to another, but that we see a relatively structured web of attention and mutual pointing that marks what is, and what is not, relevant and important to us.

It combines, first, the fact that some sites are in fact much more highly connected than others—this is the top of the power law distribution. It continues with the fact that sties cluster topically. That is, sites about politics are more densely interlinked to each other than they are to sites about bowling. Interestingly, although there is now some evidence to the contrary, it appears that when the clusters are small enough, the lower end of the distribution is less skew—the tail is fatter than the head. That is, there may be a few dozen, or even a hundred, sites, with moderate interlinking, instead of just no links or one link.

If this is true, then it suggests that topics get discussed in intensely-interlinked—and hence interested—clusters of interest, and those topics that reach the attention of this group as important get transmitted up the backbone of attention by the more highly-visible sites of the cluster, to larger clusters, and so on up.

The bow-tie structure is a pattern that emerges in networks where about 30% of the sites are densely interlinked and can be reach from and reach into any other site; and in the 20% of sites that can only reach into the core (these may be new sites, not yet liinked-to); sites than can only be reached from the core (these may be documents, or internal sites not linking further); and sites that are just not connected to the core at all. My point in focusing on this structure was that it suggested that over 50% of the sites on the ‘Net could reach out; and over 50% could be reached from almost anywhere. And by comparison to mass media, this is a vast improvement relative to who could be heard, and who could reach what information.

All this went into my claim that, while the networked public sphere was not the utopia some in the early 1990s would have liked it to be, it was certainly an appreciable and important improvement over the industrial, mass media structure of the public sphere in the century and a half that preceded it.

JT: The Wealth of Networks was described, I believe it was by Time magazine, as “utopian.” I didn’t see it that way, but rather as a book that was as full of sense as it was of hope. But it was a contingent hope: one based on things like ‘Net neutrality, gift economies, open access to information, and so on. Can you leave us with your most hard-headed vision of the hope contained in—and possibly sustained by—The Wealth of Networks?

YB: I agree that The Wealth of Networks is not utopian. I think realistically we can see a large improvement in the number of people who can effectively participate in the production of information, knowledge, and culture. I think more people are creating media; more people have access to a community or site where they can speak their minds. More does not mean everyone. Disparities in access and skill continue. But there are many more, and more diversely motivated and organized voices and creative talents participating than was feasible ten years ago, much less 30 years ago.

I think there are certain well-defined threats to this model. If we end up with a proprietary communications platform, such as the one that the FCC’s spectrum and broadband policies are aiming to achieve; and on that platform we will have proprietary, closed platforms like the iPhone, then much of the promise of the networked environment will be lost.

When the FCC and Congress had an opportunity to make parts of the 700MHz band an open spectrum, to which any device manufacturer could have built devices that would have created user-owned networks, on the model of WiFi but more powerful, they failed in imagination and wisdom. When they were presented by Google with a much thinner, but at least well-reasoned and positive, alternative, to make the 700MHz auction at least require purchasers to resell to anyone who wanted wholesale carriage, so that at least there could be competition, they balked at that too.

We now also see the rising tide of fear leading to a resurgence of “trusted systems”—systems that assume that the owners of computers are either incompetent or malevolent, so the machine has to be “trusted” against its owner. This too can undermine the openness, innovation, and expressive freedom of the networked environment. The threats are many. Some of them come from intentional efforts to hobble the ‘Net in order to preserve incumbent business models. The interventions of the telecomms and the strong copyright lobbies fall into these categories. Some come from simple lack of appreciation for the central role that open, radically decentralized platforms are playing, and it is not necessarily a regulatory mistake as a business mistake.

I am still optimistic. It does seem that people have been opting for open systems when they have been available, and that has provided a strong market push against the efforts to close down the ‘Net. Social practices, more prominently the widespread adoption of participation in peer production, social sites, and DIY media, are the strongest source of pushback. As people practice these freedoms, one hopes that they will continue to support them, politically, but most powerfully perhaps, with their buying power and the power to divert their attention to open platforms rather than closed. This, the fact that decentralized action innovates more quickly, and that people seem to crave the freedom and creativity that it gives them, is the most important force working in favor of our capturing and extending the value of an open network.

The piles of awards handed to The Virginia Quarterly Review since Ted Genoways took the helm in 2003—as well as all the press—and, most importantly, the singular experiences provided by each new issue of VQR are very nearly unprecedented in literary publishing. Truly: it’s a marvel. Ted was kind enough to lend me his time this week to discuss the changes he’s already made at VQR—but also some of the bigger shifts that are coming as blogs and broadband become more popular and the entire magazine industry is starting to wonder: what’s next?

JT: The Virginia Quarterly Review might best have been described as “venerable” when you took it over: you’ve kept the best of the old seriousness, but added a lot to the new mix: photos, comics, even pull-out posters and art. You even garnered a Best American Comics award for Art Spiegelman’s “Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@#*!” this year. Is this new look and feel something you did because things like photography and comics and other visual arts are essential to our culture—or was it also an attempt to make each VQR into something more than just the traditional “book” of quarterly journalism: something as strong as an event and artifact as it in in words and ideas? Is this something print quarterlies are going to have to do to survive?

TG: The short answer on why the magazine is so (comparatively) heavily designed is that we’re a bunch of booklovers, typophiles, and out-and-out design nerds. We love what a beautiful design can do. Gideon Mendel’s photographs of people living with AIDS in Africa, for example, were amazing when paired the testimonies of their subjects—they were no longer just words on a page; they had faces. In this way, the physical object is more than just a vessel or delivery device for the ideas it contains, but it’s also clear that more and more of our audience is finding us online. So we have to have an equally compelling and attractive web presence. Our site has to be as rich and complex as the print issue, and it has to burst with interesting content—and not just words, but also video, audio, additional photos. Like I said, we all love print—and champion it—but we always realize that things change and new possibilities emerge. I won’t be surprised if my son only reads in electronic media when he’s an adult. If that happens, I won’t be as sad as a lot of book people. To me, the magic is in the words, the way they leap from the page. You know, I’m a Whitman guy, and old Walt was a printer himself but hated the obstacles of printing. “I was chilled with the cold types, cylinder, wet paper between us,” he wrote. “I pass so poorly with paper and types, I must pass with the contact of bodies and souls.” If the web allows us to be in contact with more readers—more souls—then how could we not be thrilled by its infinite promise? I think any magazine that doesn’t recognize these new possiblities—or willfully ignores them—does so at its peril.

JT: I don’t know that I’ve paid that close attention to it, but it seems like more and more of your content is online for free—in addition to an increasing amount of online-only content. You used a Google map as an alternate Table of Contents for your latest issue, on South America in the 21st Century. How important is Web traffic to VQR? It seems like the Internet and, specifically, blog conversation is a huge opportunity for the old print quarterlies—most of whom only have a circulation of four or five figures. Do you get a lot of incoming links from online articles and blogs? Has it changed what you see as your mission? Let’s talk possibilities here.

TG: Web traffic is paramount—even more important than it was a few years ago—and for exactly the reasons you suggest. For a print magazine with a total press run of 7,000 copies, the only way to be part of the larger discussion is by using other media. In some cases that has meant getting our authors on NPR or partnering with the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting to produce news segments for PBS. But people who consume the news through those other media often aren’t big readers, so they’re not likely VQR subscribers. But the people on the Web are still primarily readers, so a recent brief mention on kottke.org of an article that we published in our current issue brought in 25,000 visits, whereas a full hour on NPR’s Fresh Air for another author hardly generated any traffic at all.

So the Web affects the way we do things—we’ve recently hired a full-time Web developer, for example, a real rarity among journals of this kind—but I don’t think it’s changed our mission per se, because it hasn’t changed what we publish. But it has certainly changed the way we approach promoting our material. It’s encouraged us to be a little more expansive, a little less buttoned-down. The Google map adds a little wow factor to our content and hopefully encourages younger readers to tackle our long pieces. This sort of thing gives us the chance to show that our material is serious, but at heart we’re just a bunch of lit nerds who still geek out over new technology.

JT: The New York Times, I’ve noticed, is offering more and better interactive content with its articles—especially their series pieces. For your South America in the 21st Century issue, you’ve put up a fantastic feature on the Urban Virgin paintings of Ana de Orbegoso, accompanied by Odi Gonzales’ poems, each of which is translated into and read in English, Spanish, and Quechua. Can we expect more of this?

TG: This is a direction that I’m anxious to move in, to see the Web as a world of possibilities for expanding our content, rather than just a different way of delivering the print edition. The Odi Gonzales poems are a great example, because we couldn’t find a good way to present those poems in all three versions in the print magazine without seriously compromising the design. But we could do that easily with a bit of JavaScript on the website. From there, I started to wonder: Since Quechua is an oral language, shouldn’t we hear these poems? And I’m so glad we did. You don’t have to be a linguist to hear the amazing internal rhymes, refrains, and rhythms of Gonzales’s poems in Quechua. That’s something that no print magazine could ever convey.

Likewise, we see the videos as opportunities to tell our stories in different ways for different audiences. It’s also another perspective, a slightly different angle that adds to and often enriches the print version. In that way, the audio and video is no different than adding photographs.

JT: OK, this last one is a bit tricky, but let’s run with it: is there any possibility for art to crop up on blogs? Have you ever read a blogger and said, “I want that guy!”? I was talking to a friend the other day and she said, “Oh, I don’t want to read blogs for essays and fiction—I just want them to point out the good stuff.” Jason Kottke is a great curator of what’s fascinating: is that the best-suited mission of blogs? Or are there as many ways of blogging, to paraphrase Thoreau, as there are radii in a circle? Pound’s Cantos were pretty ranty—would they have worked as a blog?

TG: This is a fascinating question—and I think the answer is: yes, art is cropping up on blogs. I especially feel this way about bloggers from other parts of the world. It has provided a venue for writers who normally would never have found an American audience. The Iraq war showed us that bloggers like Salam Pax and Riverbend could produce vital records of events as they happened. Riverbend, for example, wrote about meeting someone who had been abused in Abu Ghraib weeks before the story broke in The New Yorker. That blog will be an important record of this war. Does that rise to the level of art? Only time will tell for sure, but I can tell you that there are blogs—from Africa and India, in particular—that have made me aware of writers I never would have found otherwise, and some of that work (fiction primarily) is absolutely outstanding.

But I also continue to be amazed by the incredible small publications around the world. It’s not just Granta anymore. It’s also places like Etiqueta Negra and Caribbean Writing Today. The Web makes those publications readily accessible to anyone with the interest.

OK, short intro: Douglas Wolk is smart, funny, and if you have any interest in comics whatsoever you should absolutely check out his Reading Comics. Great stuff. This is a long interview, but every time I tried to cut it, I thought, “Nope, not that—too smart.” So here you go. Comments turned on, normal rules apply—enjoy.

JT: The opening of one of Robert Warshow’s essays, on Krazy Kat, is worth quoting at length, if only because it could be a sort of manifesto of sorts for blogging, writ-large:

“On the underside of our society, there are those who have no real stake at all in respectable culture. These are the open enemies of culture…. these are the readers of pulp magazines and comic books, potential book-burners, unhappy patrons of astrologers and communicants of lunatic sects, the hopelessly alienated and outclassed…. But their distance from the center gives them in the mass a degree of independence that the rest of us can achieve only individually and by discipline… when this lumpen culture displays itself in mass art forms, it can occasionally take on a purity and freshness that would almost surely be smothered higher up on the cultural scale.”

We’ll get to comics, but I wonder if this doesn’t perfectly capture some of the anarchism, snark, and general weirdness of a lot that comes across the blogosphere? Insofar as blogging remains a kind of private, gift-exchange of woe and rant and fanatical interest, isn’t this what makes blogs so much fun? So vital?

DW: There’s still a pernicious kind of defensive class-consciousness to what Warshow’s writing here, a sense of “purity and freshness” from noble savages (“potential book-burners”? same to you, buddy!), a sense that everybody knows what the cultural scale is and that it’s self-evidently immutable. That’s not really the case any more, and it hasn’t been the case for a long time. And the phrase “respectable culture” suggests that what’s at stake here maybe isn’t even culture as much as respect—the respect owed to the individual, disciplined “rest of us” by “them in the mass.” That, as they say, is a mug’s game.

To put it another way: “distance from the center” presumes not only that everybody agrees on what that center is, but that one is either near to it or far from it, and that being far from it can confer some kind of ironic virtue. This is the same kind of mindset that valorizes “outsider art” for the straw dangling from the corner of its mouth rather than for itself. What’s fun and vital about the blogosphere is not that it doesn’t speak with the questionably unified (“smothered”?) voice of mass culture, but that individual bloggers only need to speak for themselves and about their own personal interests, and don’t need to triangulate themselves against any distinct or nebulous center; it doesn’t matter who’s paying attention and who isn’t, even when lots of people are paying attention! Each blogger is a gravitational center, great or small, but there’s no sun they’re all orbiting around.

JT: In Reading Comics, you write “The blessing and the curse of comics as a medium is that there is such a thing as ‘comics culture.’” It’s unfair to ask, but can you give a shorter summary of this than you give in this chapter of your book (“What’s Good About Bad Comics and What’s Bad About Good Comics”)? How are these cultures changing—or spreading—as mainstream literary writers like Chabon and Lethem enter the fray & magazines and journals like The Virginia Quarterly Review and The New York Times Magazine have begun featuring comics regularly (or that we now have a Best American Comics)? Is the imprimatur of “official culture” the mark of death for comics culture?

DW: “Comics culture” has always been a little bit tough for me to grapple with, partly because I’m looking at it from the inside. It’s a culture that’s immersed in comics and their history and economics and formal conventions, to the point where it can be difficult to read comics casually: you almost have to adopt (or work around) a certain cultural mode to pick up something with words and pictures and read it for pleasure, and that’s annoying. On the other hand, the culture of comics-readers does privilege deep knowledge, and in its eccentric way it’s deeply committed to being hospitable to newcomers; we care about this stuff a lot, and we like the feeling of being a community.

As for the second half of your question, why would an influx of public attention, talent and money possibly mark the death of comics? If people start buying books by Jaime Hernandez and Megan Kelso because they’ve seen their work in the Times Magazine, I’m all for that—believe me, there’s nobody who’s attached to the idea of the best cartoonists remaining some kind of subcultural secret. It’s interesting to see the the way the new streams of creators are affecting comics, though—I’m particularly fond of cartoonists with backgrounds in design or contemporary visual art who’ve come to comics because they’ve gotten interested in narrative. In the last few years, there’s also been a bit of a trend of celebrity writers in the comics mainstream, some of whom have adapted easily to the different sort of writing that works in combination with drawings, and some of whom are still writing as if the images in comics are just ancillary illustrations of the important (verbal) part. But that doesn’t mean that something important has been lost, just that there’s fresh blood and sometimes a learning curve—there are more English-language comics in print now than there have ever been before, and more good stuff available than ever before.

JT: A quick Google search for “comics blogs” returns about 58 million results. Are there notable blogs out there that manifest these two sides of comics culture? Is there a killer spandex fanboy site? A Pitchfork for comics?

DW: Oh, absolutely. I’d like to say that if there’s a Pitchfork for comics, it’s The Savage Critic(s), to which I occasionally contribute—my two favorite comics critics, Joe “Jog” McCulloch and Abhay Khosla, both write for it. The best spandex sites these days, as far as I’m concerned, are Chris’s Invincible Super-Blog, Bully Says: Comics Oughta Be Fun!, The Absorbascon and Myriad Issues, with extra credit to Funnybook Babylon for “Downcounting,” their weekly savaging of DC’s “Countdown” series. And then there are great generalist blogs—the Comics Reporter is one of the first things I read every morning, and I really like the newish Picture Poetry, too.

JT: Even though I included 20 pages of graphic novel in my own book, I don’t really have a big collection: Joe Sacco’s books, Spiegelman’s Maus books, Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan, a couple of Eisner’s, Alan Moore, Marjane Satrapi’s memoirs, Clowes, Pekar, and Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics—basically: no superhero comics whatsoever. Am I just totally dropping the ball on the superhero and other serial comics?

DW: There are a bunch of worthwhile serial comics at the moment, and some of them are superhero comics—although superhero comics are very much grounded in a shared set of conventions, there are an awful lot of them, and even a lot of the best ones require a willingness to figure out how they fit into the “continuity” context of thousands of others. If you don’t like the idea of gigantic metaphors in brightly colored outfits, don’t force yourself. That said, on the superhero front right now I’m loving Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely’s “All-Star Superman” (which is deliberately un-linked to continuity) and Greg Pak, John Romita, Jr., and Klaus Janson’s “World War Hulk” (which is very heavily enmeshed with continuity), and I think a lot of Brian Michael Bendis’s “New Avengers”/”Mighty Avengers”/”Illuminati” work is really interesting—it fails as often as it works, but he’s pushing himself really hard.

The best non-superhero serial comics right now? Eric Shanower’s “Age of Bronze,” “Y: The Last Man,” “DMZ,” and I suppose “Love and Rockets” counts! Skipping serials on principle means you’re missing out in pretty much the same way that you’re missing out if you only watch movies and don’t bother with “The Wire” or “Lost” or “Arrested Development”…

JT: Given the fanatical culture of comics, it seems natural that there are a ton of comics blogs (and that a lot of comics artists would have blogs), but the comic and the graphic novel don’t really work as an online medium, do they? I tried keeping up with the New York Times Magazine’s comics section when I dropped my print subscription, but they serialize them on the Web as PDFs—and even then, they don’t read very well on my 15” MacBook Pro. Is this a fundamental nature of the beast? Or are there people out there making it work? Is there a Henry Darger out there in the blogosphere? The next Harvey Pekar (as if the current one weren’t handful enough)?

DW: Scott McCloud’s whole thing about the limitless potential of online comics hasn’t quite been borne out yet, but it’s still a very new medium. I agree that the Times’s PDFs are a dreadful idea, but there are a lot of Web-comics that have enormous readerships; it seems, in general, like daily humor strips are the format that work best so far. I love Achewood and Diesel Sweeties, in particular; as far as non-humor strips go, Dicebox is pretty wonderful. The real problem is that there’s presently no way for a cartoonist to make any money at all, let alone make a living, doing online comics (that whole “micropayment” thing seems to have fizzled); the few people whose sole employment seems to be doing them are actually making their money selling related merchandise. I this an insurmountable problem? Probably not—but nobody’s sure how to fix it yet. At least people doing print comics have a tangible object that can be exchanged for money.

As for the Darger/Pekar question, I’m not sure what you mean—when you say Henry Darger, I think of a crazed sexually obsessed hyperproductive fantasist working in total isolation (hence not somebody who’d be in the blogosphere, by definition); when you say Harvey Pekar, I think of a compulsive self-documenter (hence… everybody in the blogosphere).

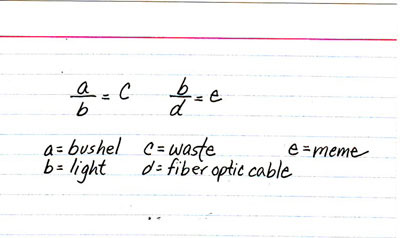

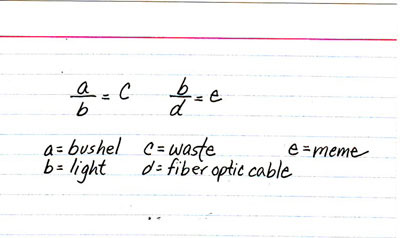

If you haven’t seen them yet (and chances are you have), Jessica Hagy’s index cards are little marvels of wit and wisdom. They’ve also netted her world-wide acclaim and a book deal with Penguin. Her book, Indexed, comes out next year. While she’s not the first blogger with a book deal, I love her cards so much I asked her to chat with me about how she started blogging—as well as how her blog got her a book deal and more. But first, here’s one of my all-time favorite Jessica Hagy index cards:

JT: So, you’re sitting around at work one day saying, “Yeah, I am like Roz Chast—but only her if maybe she worked as a McKinsey consultant, and, yes, I am going to start a blog posting my index cards, dammit!” Or did it start out a little differently?

JH: I read somewhere that ‘every writer needs a blog’ but I didn’t want to do one of those “Here’s what I had for breakfast. Here’s what I did at school” blogs. I’d had a few really lame advertising jobs, and was going back to school, and I felt like I had to do something—anything—that was remotely creative so my head wouldn’t explode. I never thought anyone would find the thing, actually. It was just my little, goofy project.

JT: Your cards are a run-away hit on the blogosphere, including their regular feature in the Freakonomics blog: did it take a while to build up? What other opportunities have grown out of your blog? Are you a full-time 3x5-er now?

JH: About a week after I posted the first batch last August, somebody linked the blog to Metafilter. Whoever you are, thank you! That’s how my agent (it’s still strange to me that I have an honest-to-god agent) found me, and from there, it just sort of took off.

I’m working on the full-timing. The Indexed book comes out on Feb 28th (one day before leap day). Indexed was a Webby honoree and is on a bunch of “best blogs’ lists. Right now, the cards are on Freakonomics and run in Plenty Magazine. They ran in GOOD magazine, on the BBC Magazine Online, and JibJab commissioned a bunch of them. Current TV is going to film me drawing about a dozen of them and turn that into TV interstitials.

I’ve had a few offers to sell the whole thing, but none seemed to be great fits. Syndication is the next thing we’re going after.

I’m super, super, super lucky.

JT: It’s blog-2-book madness these days—how did your book come about?

JH: My incredibly cool editor at Pengiun emailed me about turning the blog into a book in February. I forwarded his email to my agent. They talked to each other. I talked to them. And off we went. I love the Internet.

JT: I can’t wait for your book—but in the meantime, I hope whoever you get as a publicist uses this video of your work. How did that come about?

JH: That was an email from Clemens Kogler, an Austrian filmmaker, just saying he liked the stuff and could he use it in a film. That sounded fun to me, and the result was Le Grand Content. It was featured on the front page of YouTube on Superbowl Sunday, and having worked in advertising for years and never gotten a decent TV spot produced, that felt like a creative victory of sorts, to have that show up there when it did.

JT: Finally, care to leave us with a card about blogs?

JH:

OK, comments are turned on: be interesting or nice or both.

OK, Joel Turnipseed here. I’ll be doing some of the usual curatorial work that Jason does so well, but I also want to take this week to have a look at how blogs are changing how we create, disseminate, and critique our culture these days. In a world in which an Eau Claire Area Teen can post something to Digg and bring as much attention to it as an article in The New Yorker or The Atlantic (both of whom are heavy into blogging themselves these days), this seems like a good thing to do. For better or worse, blogs seem to be the new dispensation. But what, really, are they good for—or: what are they really good for—and what don’t they do very well? Helping me out this week will be:

Jessica Hagy, blogger and author of forthcoming Indexed

Douglas Wolk, music and comics critic and author of Reading Comics

Ted Genoways, poet and editor of The Virginia Quarterly Review

Yochai Benkler, law professor and author of The Wealth of Networks

Steven Berlin Johnson, outside.in & author, most-recently, of The Ghost Map

Jane Ciabattari, journalist, critic, and NBCC board member

Cory Doctorow, Boing Boing blogger and author of, most-recently, Overclocked

I’ll be posting short interviews with these fine folks throughout the week.

Stay Connected