kottke.org posts about books

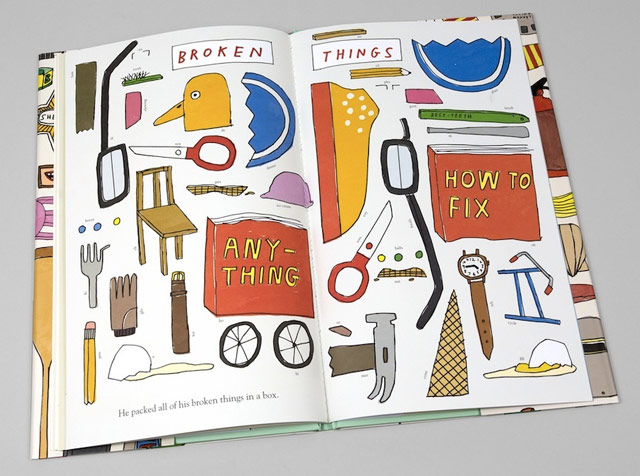

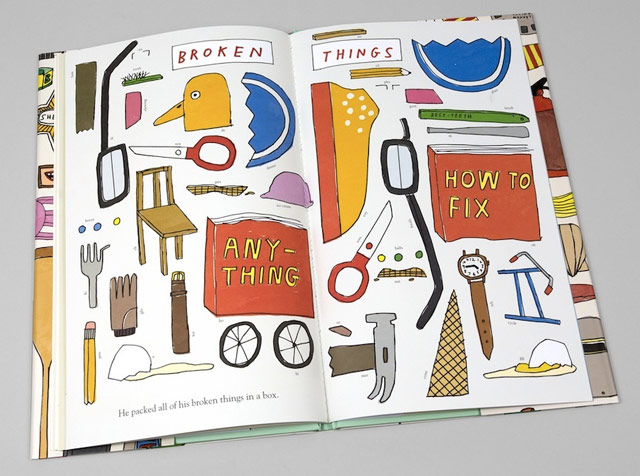

Been reading Crabtree with the kids lately and they really like it. Reminds me of Richard Scarry’s books a bit…lots of different and often humorous objects to discover on each page.

Alfred Crabtree has lost his false teeth. But don’t worry, he’ll find them if he can just get his things organized! Alfred’s world is cluttered with surprising objects. Some are very uncommon, and some are probably not where they ought to be. There are a lot of pencils and small yapping dogs.

And who knew McSweeney’s made children’s books?

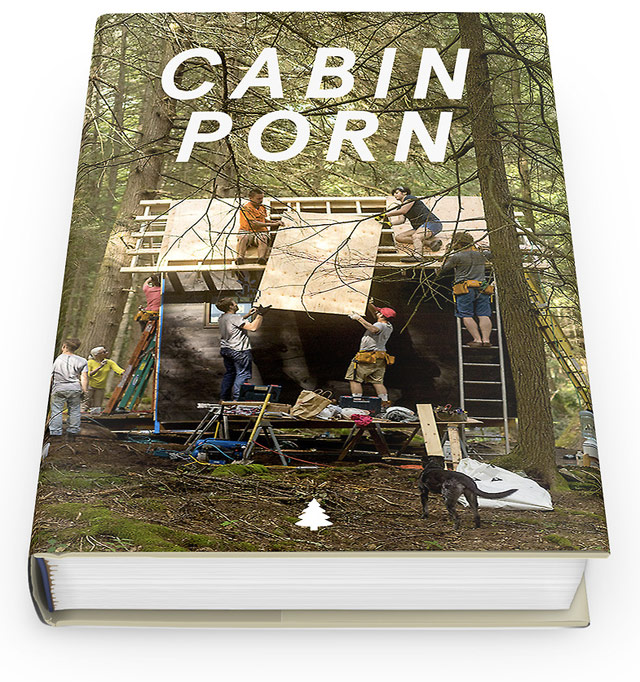

The folks behind Cabin Porn are making a book with photography by Noah Kalina. Outstanding.

Raffi Khatchadourian’s long piece on the construction of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) is at once fascinating (for science reasons) and depressing (for political/bureaucratic reasons). Fusion reactors hold incredible promise:

But if it is truly possible to bottle up a star, and to do so economically, the technology could solve the world’s energy problems for the next thirty million years, and help save the planet from environmental catastrophe. Hydrogen, a primordial element, is the most abundant atom in the universe, a potential fuel that poses little risk of scarcity. Eventually, physicists hope, commercial reactors modelled on iter will be built, too-generating terawatts of power with no carbon, virtually no pollution, and scant radioactive waste. The reactor would run on no more than seawater and lithium. It would never melt down. It would realize a yearning, as old as the story of Prometheus, to bring the light of the heavens to Earth, and bend it to humanity’s will. iter, in Latin, means “the way.”

But ITER is a collaborative effort between 35 different countries, which means the project is political, slow, and expensive.

For the machine’s creators, this process-sparking and controlling a self-sustaining synthetic star-will be the culmination of decades of preparation, billions of dollars’ worth of investment, and immeasurable ingenuity, misdirection, recalibration, infighting, heartache, and ridicule. Few engineering feats can compare, in scale, in technical complexity, in ambition or hubris. Even the iter organization, a makeshift scientific United Nations, assembled eight years ago to construct the machine, is unprecedented. Thirty-five countries, representing more than half the world’s population, are invested in the project, which is so complex to finance that it requires its own currency: the iter Unit of Account.

No one knows iter’s true cost, which may be incalculable, but estimates have been rising steadily, and a conservative figure rests at twenty billion dollars — a sum that makes iter the most expensive scientific instrument on Earth.

I wonder what the project would look like if, say, Google or Apple were to take the reins instead. In that context, it’s only $20 billion to build a tiny Sun on the Earth. Facebook just paid $19 billion for WhatsApp, Apple has a whopping $158.8 billion in cash, and Google & Microsoft both have more than $50 billion in cash. Google in particular, which is making a self-driving car and has been buying up robots by the company-full recently, might want their own tiny star.

But back to reality, the circumstances of ITER’s international construction consortium reminded me of the building of The Machine in Carl Sagan’s Contact. In the book, the countries of the world work together to make a machine of unknown function from plans beamed to them from an alien intelligence, which results in the development of several new lucrative life-enhancing technologies and generally unites humanity. In Sagan’s view, that’s the power of science. Hopefully the ITER can work through its difficulties to achieve something similar.

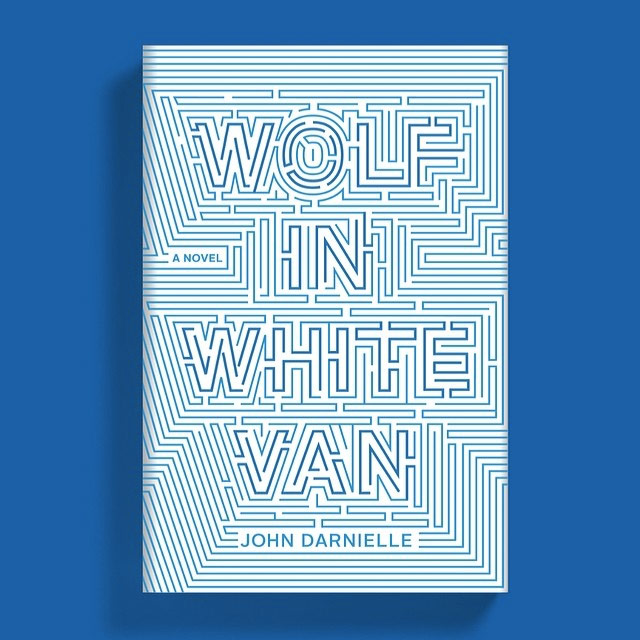

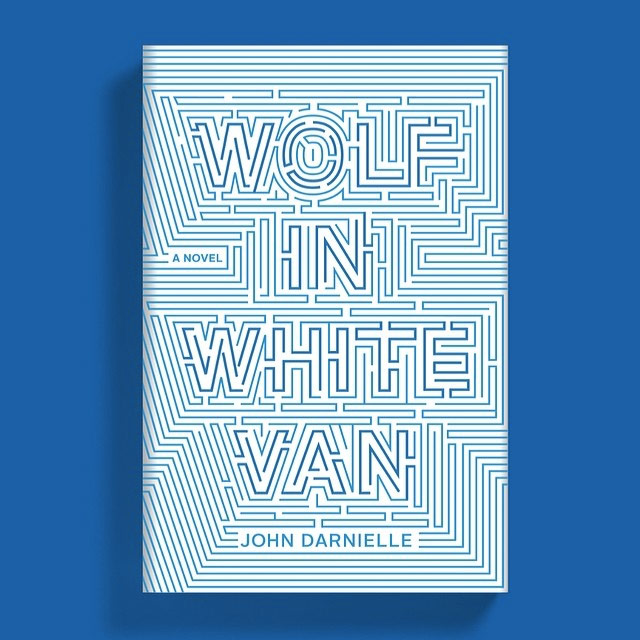

Great book cover design alert:

The book is the forthcoming Wolf in White Van by John Darnielle. Cover art direction by Rodrigo Corral, designed by Timothy Goodman. (via @robinsloan)

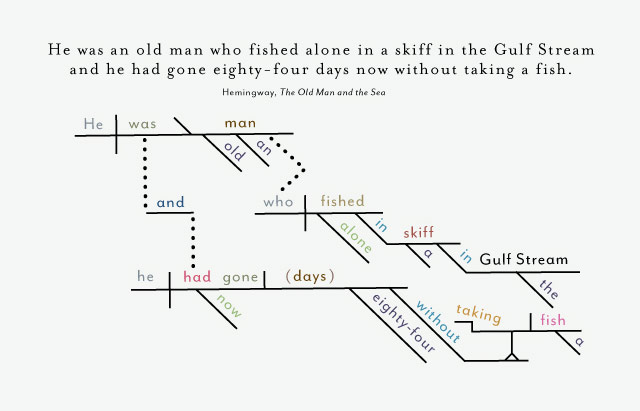

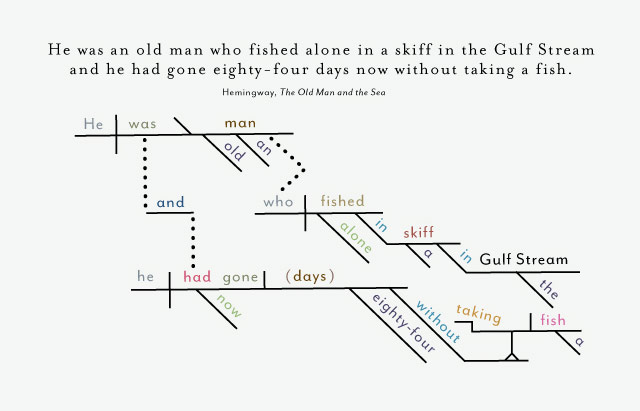

Pop Chart Lab has produced a print of grammatical diagrams of the opening lines of notable novels. Here’s Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea:

There are also sentences from DFW, Plath, and Austen. Prints start at $29.

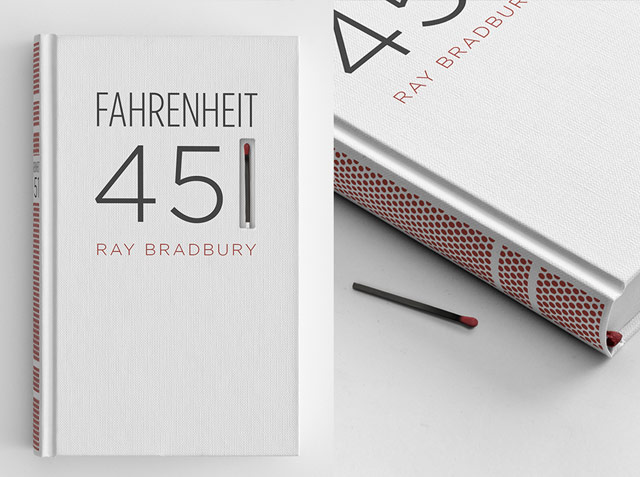

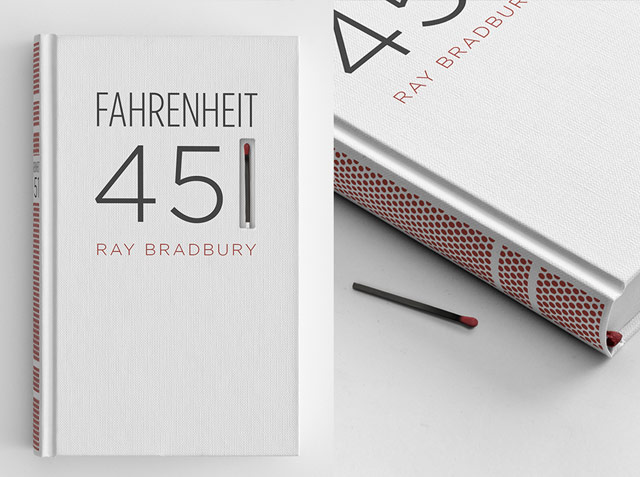

Love this concept cover for Fahrenheit 451 by designer Elizabeth Perez…the 1 is a match and the spine is striking paper for lighting it.

Fahrenheit 451 is a novel about a dystopian future where books are outlawed and firemen burn any house that contains them. The story is about suppressing ideas, and about how television destroys interest in reading literature.

I wanted to spread the book-burning message to the book itself. The book’s spine is screen-printed with a matchbook striking paper surface, so the book itself can be burned.

(via @daveg)

About 250 million years ago, Earth suffered its fifth (and worst) mass extinction event. Nearly seventy percent of land species disappeared. And they got off easy compared to marine species. Are we headed for another mass extinction on Earth? I’m not ready to break that news. But something unusual is definitely going on and extinction rates seem to be speeding up. Here’s an interesting chat with Elizabeth Kolbert, author of The Sixth Extinction.

The worst mass extinction of all time came about 250 million years ago [the Permian-Triassic extinction event]. There’s a pretty good consensus there that this was caused by a huge volcanic event that went on for a long time and released a lot of carbon-dioxide into the atmosphere. That is pretty ominous considering that we are releasing a lot of CO2 into the atmosphere and people increasingly are drawing parallels between the two events.

Rebecca Mead’s new book comes out today, My Life in Middlemarch. The New Yorker has an excerpt adapted from the book about George Eliot’s biggest fan, Alexander Main.

My copy of “Wise, Witty, and Tender Sayings,” which I bought a few years ago from a secondhand bookseller, is the tenth edition, from 1896, which gives Main an enviably long time on the back-list. When I thumb through its pages of quotations, some of them extending for more than a page, printed in a font size that has me reaching for reading glasses, I am overcome by a dreadful sense of depletion. I can think of no surer way to be put off the work of George Eliot than by trying to read the “Wise, Witty, and Tender Sayings.” On any given page is an out-of-context pronouncement — “iteration, like friction, is likely to generate heat instead of progress” — or a phrase so recondite that it requires several readings before it can be parsed. Main’s book is the nineteenth-century equivalent of the refrigerator magnet.

Gothamist uncovered a NYC guide book from the 1920s called Valentine’s City of New York: A Guide Book. Some of the tips include:

Don’t take the recommendation of strangers regarding hotels… Don’t get too friendly with plausible strangers.

Don’t gape at women smoking cigarettes in restaurants. They are harmless and respectable. They are also “smart.”

Don’t forget to tip. Tip early and tip often.

(via @DavidGrann)

David Carr writes about the surprising success of Kevin Kelly’s Cool Tools book, which is based on his long-running website of the same name.

But last year, he had what sounded to me like a dumb idea. Mr. Kelly edits and owns Cool Tools, a website that writes about neat stuff and makes small money off referral revenue from Amazon when people proceed to buy some of those things. He decided to edit the thousands of reviews that had accrued over the last 10 years into a self-published print catalog — also called “Cool Tools” — which he would then sell for $39.99.

So, to review, his idea was to manufacture a floppy 472-page catalog that would weigh 4.5 pounds, full of buying advice that had already appeared free on the web, essentially turning weightless pixels into bulky bundles of atoms. To make it happen, he crowdsourced designs from all over the world, found a printer in China and then arranged for shipping and distribution. It all seemed a little quixotic and, well, beside the point.

Except the first printing of 10,000 copies, just in time for Christmas, sold out immediately, a second printing of 12,000 will go on sale at Amazon next week and a third printing of 20,000 copies is underway. So, not so dumb after all.

I haven’t had a chance to dig too deeply into my copy yet, but my six-year-old sat down with it a few weeks ago and had about a million questions per page for me. Which seems a like a positive sign.

Magazine covers, movie posters, and book covers all have the same basic job, so it seemed proper to group these lists together: 50 [Book] Covers for 2013, The 20 best magazine covers of 2013, The 50 Best Posters Of 2013, Top [Magazine] Covers 2013, The Best Book Covers of 2013, The 30 Best Movie Posters of 2013, Best Book Covers of 2013. Lots of great work here. I still can’t figure out whether I love or hate this cover of W with George Clooney on it:

Jason Segel is set to play David Foster Wallace in a movie adaptation of David Lipsky’s Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself.

Story finds Lipsky accompanying Wallace across the country on a book tour promoting “Infinite Jest,” just as Wallace starts to become famous. Along the way, jealousy and competition bubbles up between the two writers as they discuss women, depression and the pros and cons of fame.

Reaction from the DFW fan club abut Segel playing DFW has been tepid, to say the least.

Inspired by the A History of the World in 100 Objects project done by the BBC and the British Museum, Adrian Hon presents A History of the Future in 100 Objects, presented from the perspective of someone writing in 2082. From the introduction:

Every century is extraordinary, of course. Some may be the bloodiest or the darkest; others encompass momentous social revolutions, or scientific advances, or religious and philosophical movements. The 21st century is different: it represents the first time in our history that we have truly had to question what it means to be human. It is the stories of our collective humanity that I hope to tell through the hundred objects in this book.

I tell the story of how we became more connected than ever before, with objects like Babel, Silent Messaging, the Nautilus-3, and the Brain Bubble - and how we became fragmented, both physically and culturally, with the Fourth Great Awakening, and the Biomes.

With the Braid Collective, the Loop, the Steward Medal, and the Rechartered Cities, we made tremendous steps forward on our long pursuit of greater equality and enlightenment — but the Locked Simulation Interrogations, the Sudan-Shanghai Letter, the Collingwood Meteor, and the Downvoted all showed how easy it was for us to lapse back into horror and atrocity.

We automated our economy with the UCS Deliverbots, the Mimic Scripts, the Negotiation Agents, and the Old Drones, destroying the entire notion of work and employment in the process; and we transformed our politics with Jorge Alvarez’s Presidential Campaign, and the Constitutional Blueprints.

The book is available on the Kindle.

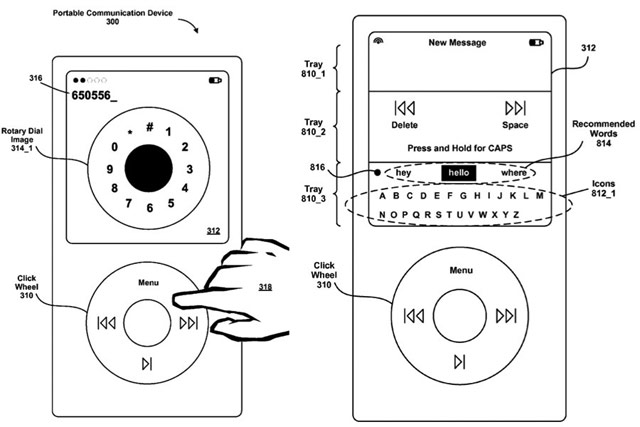

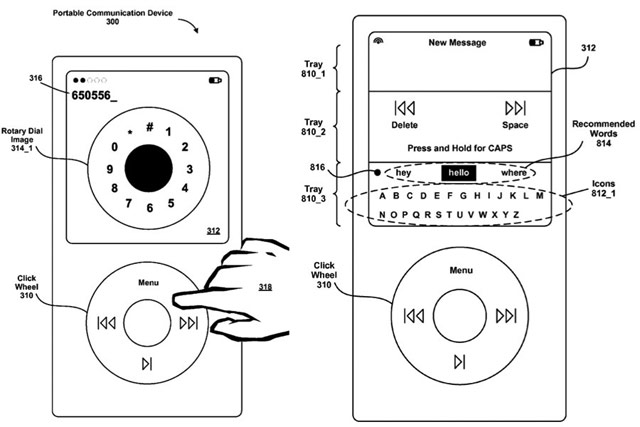

On Medium, an excerpt of Leander Kahney’s book on Jony Ive about how the iPhone came to be developed at Apple.

Excited by Kerr’s explanation of what a sophisticated touch interface could do, the team members started to brainstorm the kinds of hardware they might build with it.

The most obvious idea was a touchscreen Mac. Instead of a keyboard and mouse, users could tap on the screen of the computer to control it. One of the designers suggested a touchscreen controller that functioned as an alternate to a keyboard and mouse, a sort of virtual keyboard with soft keys.

As Satzger remembered, “We asked, How do we take a tablet, which has been around for a while, and do something more with it? Touch is one thing, but multitouch was new. You could swipe to turn a page, as opposed to finding a button on the screen that would allow you turn the page. Instead of trying to find a button to make operations, we could turn a page just like a newspaper.”

Jony in particular had always had a deep appreciation for the tactile nature of computing; he had put handles on several of his early machines specifically to encourage touching. But here was an opportunity to make the ultimate tactile device. No more keyboard, mouse, pen, or even a click wheel-the user would touch the actual interface with his or her fingers. What could be more intimate?

Ben Blatt sat down with a bunch of Where’s Waldo? books and found a pattern to the striped beanpole’s hiding places.

It may not be immediately clear from looking at this map, but my hunch that there’s a better way to hunt was right. There isn’t one corner of the page where Waldo is always hiding; readers would have already noticed if his patterns were so obvious. What we do see, as highlighted in the map below, is that 53 percent of the time Waldo is hiding within one of two 1.5-inch tall bands, one starting three inches from the bottom of the page and another one starting seven inches from the bottom, stretching across the spread.

A chart of where many varieties of bourbon come from, along with five things you can learn from the chart.

Pappy Van Winkle is frequently described by both educated and uneducated drinkers as the best bourbon on the market. It is certainly aged for longer than most premium bourbons, and has earned a near hysterical following of people scrambling to get one of the very few bottles that are released each year. Of the long-aged bourbons, it seems to be aged very gently year-to-year, and this recommends it enormously. But if you, like most people, can’t find Pappy, try W. L. Weller. There’s a 12 year old variety that retails for $23 around the corner. Pappy 15-year sells for $699-$1000 even though it’s the exact same liquid as the Pappy (same mash bill, same spirit, same barrels); the only difference is it’s aged 3 years less.

The chart is taken from the Kings County Distillery Guide to Urban Moonshining.

Written by the founders of Kings County Distillery, New York City’s first distillery since Prohibition, this spirited illustrated book explores America’s age-old love affair with whiskey. It begins with chapters on whiskey’s history and culture from 1640 to today, when the DIY trend and the classic cocktail craze have conspired to make it the next big thing. For those thirsty for practical information, the book next provides a detailed, easy-to-follow guide to safe home distilling, complete with a list of supplies, step-by-step instructions, and helpful pictures, anecdotes, and tips.

(via df)

Prolific and celebrated writer William T. Vollmann is a “devoted” cross-dresser.

Mr. Vollmann is 54, heterosexual and married with a daughter in high school. He began cross-dressing seriously about five years ago. Sometimes he transforms himself into a woman as part of a strange vision quest, aided by drugs or alcohol, to mind-meld with a female character in a book he’s writing. Other times it’s just because he likes the “smooth and slippery” feel of women’s lingerie.

He said his wife, who is an oncologist, is not thrilled with his outré experiments and keeps her distance. “Probably when the book comes out, it’ll be the first she’s heard of it,” he said. “I always try to keep my wife and child out of what I do. I don’t want to cause them any embarrassment.” He asked that his wife not be interviewed for this article.

Vollmann has collected self-portraits of himself as his female alter ego in The Book of Dolores. (via @DavidGrann)

One of my favorite books on technology, Tom Standage’s The Victorian Internet, was adapted into a TV documentary. It is now available on YouTube:

The Victorian Internet tells the colorful story of the telegraph’s creation and remarkable impact, and of the visionaries, oddballs, and eccentrics who pioneered it, from the eighteenth-century French scientist Jean-Antoine Nollet to Samuel F. B. Morse and Thomas Edison. The electric telegraph nullified distance and shrank the world quicker and further than ever before or since, and its story mirrors and predicts that of the Internet in numerous ways.

In 1898, an editor named Clement K. Shorter made a list of the 100 best novels (with an additional limit of one/author).

1. Don Quixote - 1604 - Miguel de Cervantes

2. The Holy War - 1682 - John Bunyan

3. Gil Blas - 1715 - Alain René le Sage

4. Robinson Crusoe - 1719 - Daniel Defoe

5. Gulliver’s Travels - 1726 - Jonathan Swift

6. Roderick Random - 1748 - Tobias Smollett

7. Clarissa - 1749 - Samuel Richardson

8. Tom Jones - 1749 - Henry Fielding

9. Candide - 1756 - Françoise de Voltaire

10. Rasselas - 1759 - Samuel Johnson

So much on there I’ve never even heard of. Compare this list with that of the best novels of the 20th century…how many of those novels and authors will readers be scratching their heads over in 2113? See also a contemporary list of the best books from before 1900. (via mr)

Earlier this year, Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry was subjected to a review by the Board of Education and was found wanting in several areas.

Pupils at Hogwarts have access to a reasonably wide range of esoteric qualifications, suited to its key demographic. As an independent school, it does not have to follow the National Curriculum closely; however, it is disappointing to note that basic requirements such as English, Mathematics and Religious Education are all lacking or entirely missing from the school’s syllabus. This has had adverse effects on all students, many of whom have never even been taught basic KS1 or 2 literacy. A few students have attended state or independent primary schools, and these students typically perform very well in contrast to their peers.

The majority of students appear to be under-performing, with most pupils struggling in all their lessons, most of which appear to be set at too challenging a level. One particular class, which seemed to be based on A-Level chemistry, proved too difficult for even the most proficient students. Only one pupil managed to complete the lesson objectives, mainly thanks to his use of an annotated text book.

(via slate)

Hmm, this looks interesting: an upcoming book on the science of booze written by Adam Rogers.

In Proof, Adam Rogers reveals alcohol as a miracle of science, going deep into the pleasures of making and drinking booze-and the effects of the latter. The people who make and sell alcohol may talk about history and tradition, but alcohol production is really powered by physics, molecular biology, organic chemistry, and a bit of metallurgy-and our taste for those products is a melding of psychology and neurobiology.

Proof takes readers from the whisky-making mecca of the Scottish Highlands to the oenology labs at UC Davis, from Kentucky bourbon country to the most sophisticated gene-sequencing labs in the world — and to more than one bar — bringing to life the motley characters and evolving science behind the latest developments in boozy technology.

Rogers wrote the piece about the mystery whiskey fungus I linked to a couple of years ago.

In New York Magazine this week, Mike Tyson writes about growing up in Brooklyn and his discovery of boxing as a way out and up.

Having to wear glasses in the first grade was a real turning point in my life. My mother had me tested, and it turned out I was nearsighted, so she made me get glasses. They were so bad. One day I was leaving school at lunchtime to go home and I had some meatballs from the cafeteria wrapped up in aluminum to keep them hot. This guy came up to me and said, “Hey, you got any money?” I said, “No.” He started picking my pockets and searching me, and he tried to take my fucking meatballs. I was resisting, going, “No, no, no!” I would let the bullies take my money, but I never let them take my food. I was hunched over like a human shield, protecting my meatballs. So he started hitting me in the head and then took my glasses and put them down the gas tank of a truck. I ran home, but he didn’t get my meatballs. I still feel like a coward to this day because of that bullying. That’s a wild feeling, being that helpless. You never ever forget that feeling. That was the last day I went to school. I was 7 years old, and I just never went back to class.

The piece is adapted from Tyson’s upcoming memoir, Undisputed Truth. Tyson wrote the book with Larry Sloman, author of Reefer Madness who has also ghostwritten for Howard Stern, Anthony Kiedis, and KISS’s Peter Criss.

Update: Spike Lee directed a documentary version of Undisputed Truth; it’ll air on HBO on November 16. Here’s the trailer:

Matt Zoller Seitz is doing a video essay series based on his new book, The Wes Anderson Collection. The first two installments, on Bottle Rocket and Rushmore, are already up:

I love what he says about Rushmore:

There are few perfect movies. This is one of them.

The book and video essays came about because Anderson saw Seitz’s earlier video essay series, The Substance of Style, an examination of Anderson’s stylistic influences. Great resource for fans of Anderson and film.

As a belated recognition of Exploration Day, here’s Charles C. Mann’s piece on the history of the Americas before Columbus: 1491. This piece blew my doors off when I first read it.

Before it became the New World, the Western Hemisphere was vastly more populous and sophisticated than has been thought-an altogether more salubrious place to live at the time than, say, Europe. New evidence of both the extent of the population and its agricultural advancement leads to a remarkable conjecture: the Amazon rain forest may be largely a human artifact.

This article spawned a book of the same name, which is one of my favorite non-fiction reads of the past decade.

In a book called All Things Considered published in 1915, G.K. Chesterton deftly skewers the glut of books by gurus, articles linked to from Hacker News, and conference talks by entrepreneurs about how to be successful.

That a thing is successful merely means that it is; a millionaire is successful in being a millionaire and a donkey in being a donkey. Any live man has succeeded in living; any dead man may have succeeded in committing suicide. But, passing over the bad logic and bad philosophy in the phrase, we may take it, as these writers do, in the ordinary sense of success in obtaining money or worldly position. These writers profess to tell the ordinary man how he may succeed in his trade or speculation-how, if he is a builder, he may succeed as a builder; how, if he is a stockbroker, he may succeed as a stockbroker. They profess to show him how, if he is a grocer, he may become a sporting yachtsman; how, if he is a tenth-rate journalist, he may become a peer; and how, if he is a German Jew, he may become an Anglo-Saxon. This is a definite and business-like proposal, and I really think that the people who buy these books (if any people do buy them) have a moral, if not a legal, right to ask for their money back. Nobody would dare to publish a book about electricity which literally told one nothing about electricity; no one would dare publish an article on botany which showed that the writer did not know which end of a plant grew in the earth. Yet our modern world is full of books about Success and successful people which literally contain no kind of idea, and scarcely any kind of verbal sense.

Chesterton continues:

It is perfectly obvious that in any decent occupation (such as bricklaying or writing books) there are only two ways (in any special sense) of succeeding. One is by doing very good work, the other is by cheating. Both are much too simple to require any literary explanation. If you are in for the high jump, either jump higher than any one else, or manage somehow to pretend that you have done so. If you want to succeed at whist, either be a good whist-player, or play with marked cards. You may want a book about jumping; you may want a book about whist; you may want a book about cheating at whist. But you cannot want a book about Success. Especially you cannot want a book about Success such as those which you can now find scattered by the hundred about the book-market. You may want to jump or to play cards; but you do not want to read wandering statements to the effect that jumping is jumping, or that games are won by winners.

That Chesterton’s observations ring so true today is not an accident. The last time income inequality in the US was as high as it is today? The 1910s and 1920s. (via mustapha abiola)

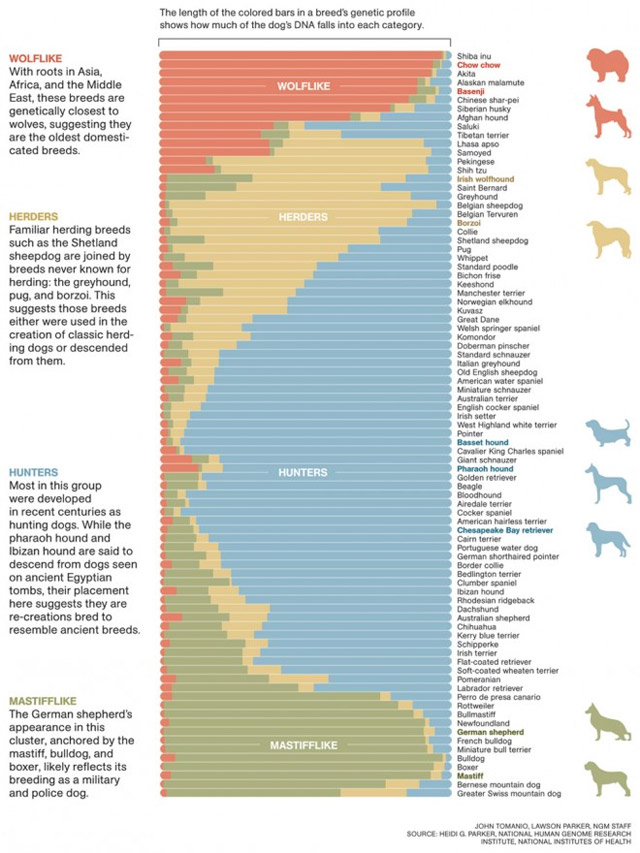

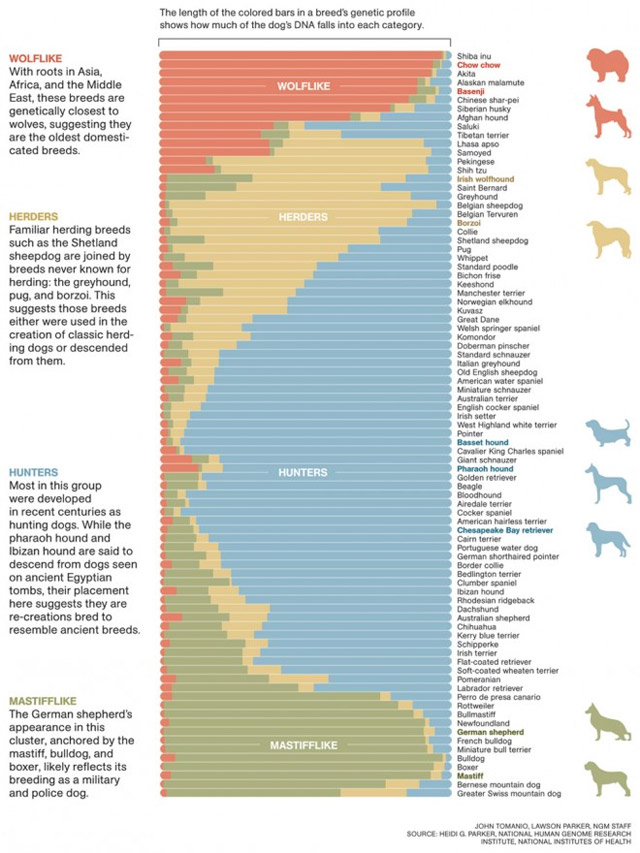

Sadly, most infographics these days look like this, functioning as a cheap and easy way to gussy up numbers. But when done properly, infographics are very effective in communicating a lot of information in a short period of time and can help you see data in new ways. In The Best American Infographics 2013, Gareth Cook collects some of the best ones from over the past year. Wired has a look at some of the selections.

Out today is The Wes Anderson Collection (at Amazon), a coffee-table book about Wes Anderson’s career.

The Wes Anderson Collection is the first in-depth overview of Anderson’s filmography, guiding readers through his life and career. Previously unpublished photos, artwork, and ephemera complement a book-length conversation between Anderson and award-winning critic Matt Zoller Seitz. The interview and images are woven together in a meticulously designed book that captures the spirit of his films: melancholy and playful, wise and childish — and thoroughly original.

Vulture has an excerpt of the chapter on The Royal Tenenbaums.

Q: Gene Hackman - it was always your dream for him to play Royal?

A: It was written for him against his wishes.

Q: I’m gathering he was not an easy person to get.

A: He was difficult to get.

Q: What were his hesitations? Did he ever tell you?

A: Yeah: no money. He’s been doing movies for a long time, and he didn’t want to work sixty days on a movie. I don’t know the last time he had done a movie where he had to be there for the whole movie and the money was not good. There was no money. There were too many movie stars, and there was no way to pay. You can’t pay a million dollars to each actor if you’ve got nine movie stars or whatever it is - that’s half the budget of the movie. I mean, nobody’s going to fund it anymore, so that means it’s scale.

That’s right, Gene Hackman (and probably the rest of them as well) worked for scale on The Royal Tenenbaums.

Anderson also talks about the scene in The Darjeeling Limited where they show everyone on the train:

Q: When you turn to reveal the tiger, what is that, the other side of the train?

A: No, it’s all one car. We gutted a car, and that is a fake forest that we built on the train, and it is a Jim Henson creature on our train car. The whole thing is one take, and I think because we did it that way, while we were doing it, we did feel this electricity, you know? There’s tension in it because it’s all real. Fake but real. I mean, that was the idea. The emotion of it, well — there’s nothing really happening in the scene, you know? They just kind of sit there, but it was a real thing that was happening. But I did at the time have this feeling like “I don’t know.”

Even if it’s fake, it’s real.

In what appears to be an excerpt from Fred Vogelstein’s new book on the Apple/Google mobile rivalry, a piece from the NY Times Magazine on how the iPhone went from conception to launch. That the Macworld keynote/demo of the phone went off so well is amazing and probably even a bit lucky.

The iPhone could play a section of a song or a video, but it couldn’t play an entire clip reliably without crashing. It worked fine if you sent an e-mail and then surfed the Web. If you did those things in reverse, however, it might not. Hours of trial and error had helped the iPhone team develop what engineers called “the golden path,” a specific set of tasks, performed in a specific way and order, that made the phone look as if it worked.

But even when Jobs stayed on the golden path, all manner of last-minute workarounds were required to make the iPhone functional. On announcement day, the software that ran Grignon’s radios still had bugs. So, too, did the software that managed the iPhone’s memory. And no one knew whether the extra electronics Jobs demanded the demo phones include would make these problems worse.

Here’s video of Jobs’ presentation that day:

According to an upcoming book by ESPN reporters Mark Fainaru-Wada and Steve Fainaru, the NFL “conducted a two-decade campaign to deny a growing body of scientific research that showed a link between playing football and brain damage”.

Excerpts published Wednesday by ESPN The Magazine and Sports Illustrated from the book, “League of Denial: The NFL, Concussions and the Battle for Truth,” report that the NFL used its power and resources to discredit independent scientists and their work; that the league cited research data that minimized the dangers of concussions while emphasizing the league’s own flawed research; and that league executives employed an aggressive public relations strategy designed to keep the public unaware of what league executives really knew about the effects of playing the game.

Excerpts of the book are available from ESPN The Magazine and Sports Illustrated. An episode of Frontline based in part on the book airs next week. Interestingly, ESPN was collaborating with Frontline on this program, but they pulled out of it in August.

Huh, Malcolm Gladwell has a new book out: David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants. Here’s the synopsis:

Three thousand years ago on a battlefield in ancient Palestine, a shepherd boy felled a mighty warrior with nothing more than a stone and a sling, and ever since then the names of David and Goliath have stood for battles between underdogs and giants. David’s victory was improbable and miraculous. He shouldn’t have won.

Or should he have?

In David and Goliath, Malcolm Gladwell challenges how we think about obstacles and disadvantages, offering a new interpretation of what it means to be discriminated against, or cope with a disability, or lose a parent, or attend a mediocre school, or suffer from any number of other apparent setbacks.

Tyler Cowen liked it:

Take the book’s central message to be “here’s how to think more deeply about what you are seeing.” To be sure, this is not a book for econometricians, but it so unambiguously improves the quality of the usual public debates, in addition to entertaining and inspiring and informing us, I am very happy to recommend it to anyone who might be tempted.

Christopher Chabris at the Wall Street Journal was not so kind:

One thing “David and Goliath” shows is that Mr. Gladwell has not changed his own strategy, despite serious criticism of his prior work. What he presents are mostly just intriguing possibilities and musings about human behavior, but what his publisher sells them as, and what his readers may incorrectly take them for, are lawful, causal rules that explain how the world really works. Mr. Gladwell should acknowledge when he is speculating or working with thin evidentiary soup. Yet far from abandoning his hand or even standing pat, Mr. Gladwell has doubled down. This will surely bring more success to a Goliath of nonfiction writing, but not to his readers.

I enjoy Gladwell’s writing and am able to take it with the proper portion of salt…I read (and write about) most pop science as science fiction: good for thinking about things in novel ways but not so great for basing your cancer treatment on. I skipped Outliers but maybe I should give this one a try?

Newer posts

Older posts

Stay Connected