kottke.org posts about oil

This morning, I randomly ran across this New Yorker review of a memoir by Tabitha Lasley called Sea State. I couldn’t stop reading it, this review, and went down a rabbit hole of other reviews of the book: the NY Times, the Guardian, and the London Review of Books.

After losing four years of progress on a novel, Lasley’s work on Sea State began when she visited Aberdeen, Scotland to research what life is like for oil rig workers, saying she “wanted to see what men were like with no women around”. And then, more or less immediately, she started a relationship with one of her (married) subjects.

Lasley’s first interviewee is an offshore worker from Teesside, an area that was once a hub of steel and chemical manufacturing. Caden has clear blue eyes, a jockey’s body, and tattoos of the names of his wife and twin daughters. He likes the gym, ironing, the autobiographies of Mafia dons, and bio-pics about soccer hooligans. Lasley spots him at an airport, where his kit bag — a kind of waterproof duffel, designed in accordance with helicopter requirements — gives him away. She approaches him, explains her project, and asks for his contact details. Caden demurs, but gives her number to a friend, who invites her to a pub with a group of fellow-riggers. Afterward, Lasley invites Caden to her hotel. Within weeks, he’s skiving off family life to sleep with Lasley in airport hotel rooms, laying the blame on the state of the sea — too rough for the chopper to take off — for not being able to make it home.

Now involved and “around”, Lasley turned the book into a hybrid: personal memoir + a class-oriented look at the concentrated masculinity of life aboard oil rigs. And somehow, according to the reviews, this actually works. Fascinating!

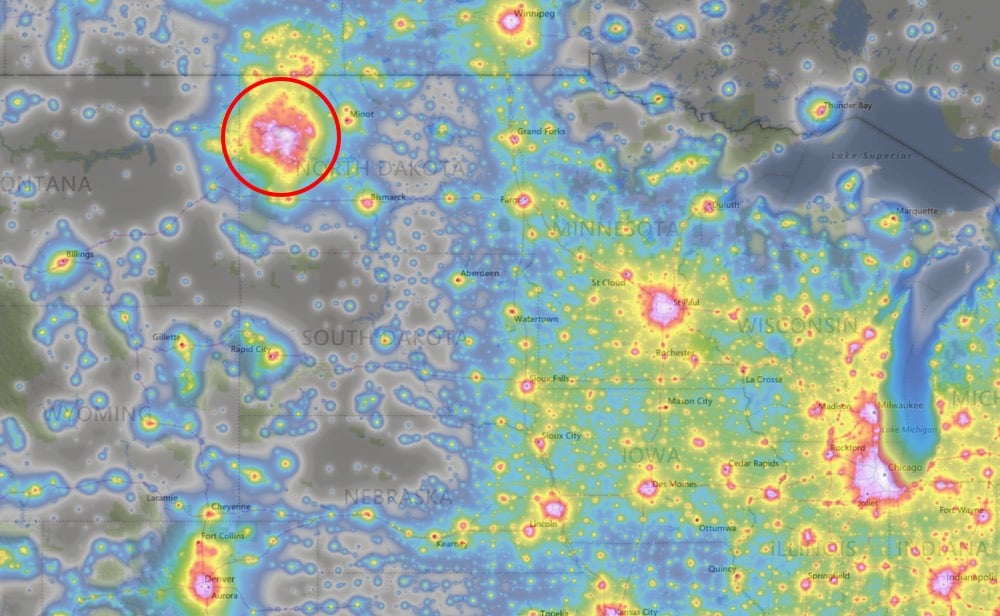

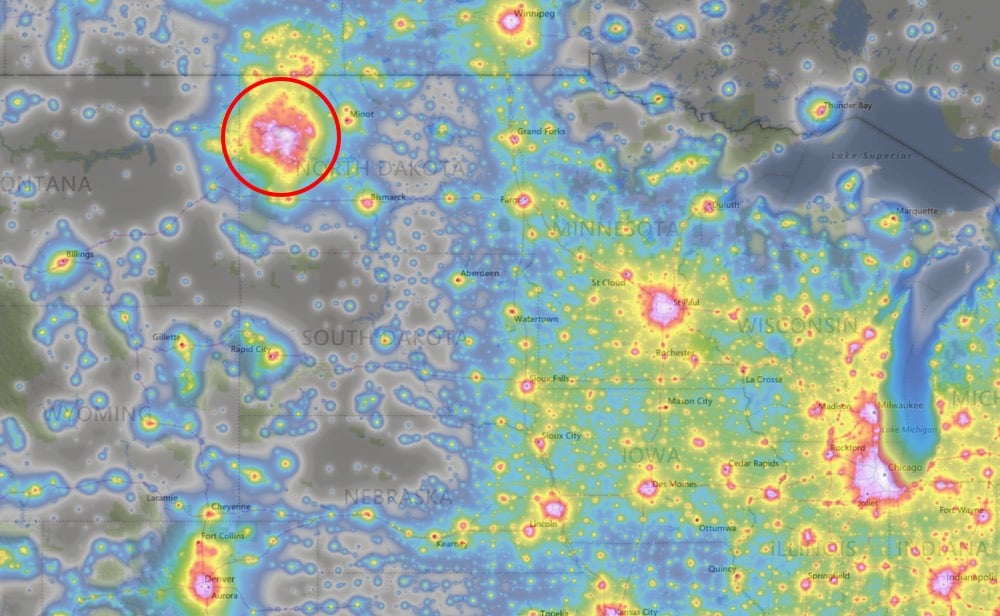

If you look at online light pollution maps, most light pollution comes from cities, but Alex Altair noticed that there are some unexpected sources of light out there as well. For instance, this sprawling site in North Dakota is one of the brightest places in the country despite what Altair calls “an intense lack of urbanization”.

The light in that area is from oil drilling & extraction in the area.

The light pollution comes from the associated gas flares. These flares are deliberate, continuously burning fires, and they convert methane, a potent greenhouse gas, into CO2, a much less potent greenhouse gas.

Intense heat also accounts for an odd light source in Hawaii — you can probably guess, but you’ll have to click through to confirm.

See also Lost in Light: How Light Pollution Obscures Our View of the Night Sky.

In just the past 10 years, the number of earthquakes in the central US (and particularly Oklahoma) has risen dramatically. In the 7-year period ending in 2016, there were more than three times the number of magnitude 3.0+ earthquakes than in the previous 36 years. Above is a video timeline of Oklahoma earthquakes from 2004-2016. At around the midpoint of the video, you’ll probably say, “wow, that’s crazy”. Keep watching.

These earthquakes are induced earthquakes, i.e. they are caused by humans. Fracking can cause induced earthquakes but the primary cause is pumping wastewater back into the ground. From the United States Geological Survey’s page on induced earthquake myths & misconceptions (a summarized version of this paper):

Wastewater disposal wells typically operate for longer durations and inject much more fluid than hydraulic fracturing, making them more likely to induce earthquakes. Enhanced oil recovery injects fluid into rock layers where oil and gas have already been extracted, while wastewater injection often occurs in never-before-touched rocks. Therefore, wastewater injection can raise pressure levels more than enhanced oil recovery, and thus increases the likelihood of induced earthquakes.

Of course, this wastewater is a byproduct of any oil & gas production, including fracking. But specifically in Oklahoma’s case, the induced earthquakes have relatively little to do with fracking:

In contrast, in Oklahoma spent hydraulic fracturing fluid represents 10% or less of the fluids disposed of in salt-water disposal wells in Oklahoma (Murray, 2013). The vast majority of the fluid that is disposed of in disposal wells in Oklahoma is produced water. Produced water is the salty brine from ancient oceans that was entrapped in the rocks when the sediments were deposited. This water is trapped in the same pore space as oil and gas, and as oil and gas is extracted, the produced water is extracted with it. Produced water often must be disposed in injection wells because it is frequently laden with dissolved salts, minerals, and occasionally other materials that make it unsuitable for other uses.

Today’s drop in crude-oil prices, which began in the summer of 2014, may be as disruptive as the quadrupling of oil prices that created the oil shock of 1974.

For most of us, lower oil prices simply translate as better prices at the gas pump. But the value of oil has big consequences around the world. From Moisés Naím in The Atlantic: The Hidden Effects of Cheap Oil.

Writing for The Atlantic, Charles C. Mann writes about a little-exploited fossil fuel called methane hydrate (“crystalline natural gas”) that is present in the Earth’s crust in great quantities…”by some estimates, it is twice as abundant as all other fossil fuels combined”.

If methane hydrate allows much of the world to switch from oil to gas, the conversion would undermine governments that depend on oil revenues, especially petro-autocracies like Russia, Iran, Venezuela, Iraq, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia. Unless oil states are exceptionally well run, a gush of petroleum revenues can actually weaken their economies by crowding out other business. Worse, most oil nations are so corrupt that social scientists argue over whether there is an inherent bond-a “resource curse”-between big petroleum deposits and political malfeasance. It seems safe to say that few Americans would be upset if a plunge in demand eliminated these countries’ hold over the U.S. economy. But those same people might not relish the global instability — a belt of financial and political turmoil from Venezuela to Turkmenistan — that their collapse could well unleash.

On a broader level still, cheap, plentiful natural gas throws a wrench into efforts to combat climate change. Avoiding the worst effects of climate change, scientists increasingly believe, will require “a complete phase-out of carbon emissions… over 50 years,” in the words of one widely touted scientific estimate that appeared in January. A big, necessary step toward that goal is moving away from coal, still the second-most-important energy source worldwide. Natural gas burns so much cleaner than coal that converting power plants from coal to gas-a switch promoted by the deluge of gas from fracking-has already reduced U.S. greenhouse-gas emissions to their lowest levels since Newt Gingrich’s heyday.

A fascinating piece by Nathaniel Rich about deep water diving. I had no idea that people building marine oil wells live for weeks at a time at depths of 1000 feet.

Not everybody is cut out for the job. A diver cannot be claustrophobic or antisocial, because he must spend much of his time in a tiny sealed capsule with several other divers. He must be well-disciplined and perceptive, for he is likely to encounter a variety of unexpected hazards on the job. Many divers are military veterans, or have worked as roofers or mechanics. “The best are those who have a great deal of confidence in themselves and their abilities,” one former diver, Phil Newsum, told me. “You have to be willing to adapt to any situation. Philosophically, when you go out on a dive job, you’re expecting something is going to go wrong.”

Often, because of the depth, the job is performed in the dark, with only a headlamp to light the way. Divers have told me stories of sudden encounters with manta rays, bull sharks, and wolf eels, which can grow eight feet long and have baleful, recessed eyes, a shovel-shaped snout, and a wide, snaggletoothed mouth. One diver sent me a video, filmed from a camera in the diver’s helmet, of an enormous turtle that was playing a game of trying to bite off the diver’s feet and hands every few minutes. The diver finally sent the animal swimming away by pressing a power drill to its head. Someone else sent me a photograph of a diver riding a speckled whale shark, as if on a rodeo bronco.

Newsum, who is now the director of an industry group called the Association of Diving Contractors International (ADCI), estimates that only three of every fifteen people who graduate from commercial diving school are able to withstand the rigor of the profession for a full career. Many are enticed by the high salaries, but few can endure the job’s physical and psychological toll. Those who stick it out tend to do so out of a passion for the job’s eccentricities.

The life of a commercial diver is somewhat less stable than that of a traveling salesman or mercenary soldier. He does not make his own schedule and has little control over his own fate, which is one reason why divers between jobs have a reputation for, as Newsum puts it, “living hard.” The diver never knows when his next job will come, but as soon as he gets called for an assignment, he must head directly to the nearest port or helicopter pad. A successful diver will work offshore about 160 days a year, cumulatively. A job might last a day, or two months. Work is most consistent, at least in the Gulf of Mexico, in the warmer months, from late March through November, but hurricane season falls within that period. Hurricanes are a mixed blessing-they disrupt ongoing jobs, but they create new ones.

This weekend’s NY Times Magazine has a long piece on the oil boom happening right now in North Dakota.

It’s hard to think of what oil hasn’t done to life in the small communities of western North Dakota, good and bad. It has minted millionaires, paid off mortgages, created businesses; it has raised rents, stressed roads, vexed planners and overwhelmed schools; it has polluted streams, spoiled fields and boosted crime. It has confounded kids running lemonade stands: 50 cents a cup but your customer has only hundreds in his payday wallet. Oil has financed multimillion-dollar recreation centers and new hospital wings. It has fitted highways with passing lanes and rumble strips. It has forced McDonald’s to offer bonuses and brought job seekers from all over the country - truck drivers, frack hands, pipe fitters, teachers, manicurists, strippers.

The Times also sent photographer Alec Soth to photograph and talk to people in the area.

“Over and over again, almost every single conversation I had, I ended up talking about Walmart,” says Soth, the photographer. “It’s the center of the culture, in a lot of ways.”

The operations there are so extensive that they can be seen in nighttime satellite photos.

What we have here is an immense and startlingly new oil and gas field - nighttime evidence of an oil boom created by a technology called fracking. Those lights are rigs, hundreds of them, lit at night, or fiery flares of natural gas. One hundred fifty oil companies, big ones, little ones, wildcatters, have flooded this region, drilling up to eight new wells every day on what is called the Bakken formation. Altogether, they are now producing 660,000 barrels a day — double the output two years ago — so that in no time at all, North Dakota is now the second-largest oil producing state in America. Only Texas produces more, and those lights are a sign that this region is now on fire … to a disturbing degree. Literally.

(via @youngna)

Earlier this morning in a post about Apple manufacturing their products in the US, I wrote “look for this “made in the USA” thing to turn into a trend”. Well, Made in the USA is already emerging as a trend in the media. On Tuesday, Farhad Manjoo wrote about American Giant, a company who makes the world’s best hoodie entirely in the US for a decent price.

For one thing, Winthrop had figured out a way to do what most people in the apparel industry consider impossible: He’s making clothes entirely in the United States, and he’s doing so at costs that aren’t prohibitive. American Apparel does something similar, of course, but not especially profitably, and its clothes are very low quality. Winthrop, on the other hand, has found a way to make apparel that harks back to the industry’s heyday, when clothes used to be made to last. “I grew up with a sweatshirt that my father had given me from the U.S. Navy back in the ’50s, and it’s still in my closet,” he told me. “It was this fantastic, classic American-made garment — it looks better today than it did 35, 40 years ago, because like an old pair of denim, it has taken on a very personal quality over the years.”

The Atlantic has a pair of articles in their December issue, Charles Fishman’s The Insourcing Boom:

Yet this year, something curious and hopeful has begun to happen, something that cannot be explained merely by the ebbing of the Great Recession, and with it the cyclical return of recently laid-off workers. On February 10, [General Electric’s Appliance Park in Louisville, KY] opened an all-new assembly line in Building 2 — largely dormant for 14 years — to make cutting-edge, low-energy water heaters. It was the first new assembly line at Appliance Park in 55 years — and the water heaters it began making had previously been made for GE in a Chinese contract factory.

On March 20, just 39 days later, Appliance Park opened a second new assembly line, this one in Building 5, to make new high-tech French-door refrigerators. The top-end model can sense the size of the container you place beneath its purified-water spigot, and shuts the spigot off automatically when the container is full. These refrigerators are the latest versions of a style that for years has been made in Mexico.

Another assembly line is under construction in Building 3, to make a new stainless-steel dishwasher starting in early 2013. Building 1 is getting an assembly line to make the trendy front-loading washers and matching dryers Americans are enamored of; GE has never before made those in the United States. And Appliance Park already has new plastics-manufacturing facilities to make parts for these appliances, including simple items like the plastic-coated wire racks that go in the dishwashers.

and James Fallows’ Mr. China Comes to America:

What I saw at these Chinese sites was surprisingly different from what I’d seen on previous factory tours, reflecting the political, economic, technological, and especially social pressures that are roiling China now. In conjunction with significant changes in the American business and technological landscape that I recently saw in San Francisco, these changes portend better possibilities for American manufacturers and American job growth than at any other time since Rust Belt desolation and the hollowing-out of the American working class came to seem the grim inevitabilities of the globalized industrial age.

For the first time in memory, I’ve heard “product people” sound optimistic about hardware projects they want to launch and facilities they want to build not just in Asia but also in the United States. When I visited factories in the upper Midwest for magazine stories in the early 1980s, “manufacturing in America” was already becoming synonymous with “Rust Belt” and “sunset industry.” Ambitious, well-educated people who had a choice were already headed for cleaner, faster-growing possibilities — in consulting, finance, software, biotech, anything but things. At the start of the ’80s, about one American worker in five had a job in the manufacturing sector. Now it’s about one in 10.

Add to that all of the activity on Etsy and the many manufactured-goods projects on Kickstarter that are going “Made in the USA” (like Flint & Tinder underwear (buy now!)) and yeah, this is definitely a thing.

As noted by Fishman in his piece, one of the reasons US manufacturing is competitive again is the low price of natural gas. From a piece in SupplyChainDigest in October:

Several industries, noticeable chemicals and fertilizers, use lots of natural gas. Fracking and other unconventional techniques have already unlocked huge supplies of natural gas, which is why natural gas prices in the US are at historic lows and much lower than the rest of the world.

Right now, nat gas prices are under $3.00 per thousand cubic, down dramatically from about three times that in 2008 and even higher in 2006. Meanwhile, natural gas prices are about $10.00 right now in Europe and $15.00 in parts of Asia.

Much of the growing natural gas reserves come from the Marcellus shale formation that runs through Western New York and Pennsylvania, Southeast Ohio, and most of West Virginia. North Dakota in the upper Midwest also is developing into a major supplier of both oil and natural gas.

So basically, energy in the US is cheap right now and will likely remain cheap for years to come because hydraulic fracturing (aka fracking aka that thing that people say makes their water taste bad, among other issues) has unlocked vast and previously unavailable reserves of oil and natural gas that will take years to fully exploit. A recent report by the International Energy Agency suggests that the US is on track to become the world’s biggest oil producer by 2020 (passing both Saudi Arabia and Russia) and could be “all but self-sufficient” in energy by 2030.

By about 2020, the United States will overtake Saudi Arabia as the world’s largest oil producer and put North America as a whole on track to become a net exporter of oil as soon as 2030, according to a report from the International Energy Agency.

The change would dramatically alter the face of global oil markets, placing the U.S., which currently imports about 45 percent of the oil it uses and about 20 percent of its total energy needs, in a position of unexpected power. The nation likely will become “all but self-sufficient” in energy by 2030, representing “a dramatic reversal of the trend seen in most other energy-importing countries,” the IEA survey says.

So yay for “Made in the USA” but all this cheap energy could wreak havoc on the environment, hinder development of greener alternatives to fossil fuels (the only way green will win is to compete on price), and “artificially” prop up a US economy that otherwise might be stagnating. (thx, @rfburton, @JordanRVance, @technorav)

Since the companies mining the oil from the sands of Alberta wouldn’t provide access to their operations to a reporter, he rented a plane and took a bunch of photos.

As Stewart said, “Better than I thought”.

Russia is building eight floating nuclear power stations for deployment in the Arctic Ocean to support their efforts to drill for oil near the North Pole.

He says each power station, costing $400m, can supply electricity and heating for communities of up to 45,000 people and can stay on location for 12 years before needing to be serviced back in St Petersburg.

And while initially they will be positioned next to Arctic bases along the North coast, there are plans for floating nuclear power stations to be taken out to sea near large gas rigs.

“We can guarantee the safety of our units one hundred per cent, all risks are absolutely ruled out,” says Mr Zavyalov.

Yeah, what could possibly go wrong? (via @polarben)

The Onion reports:

As the crisis in the Gulf of Mexico entered its eighth week Wednesday, fears continued to grow that the massive flow of bullshit still gushing from the headquarters of oil giant BP could prove catastrophic if nothing is done to contain it. The toxic bullshit, which began to spew from the mouths of BP executives shortly after the explosion of the Deepwater Horizon oil rig in April, has completely devastated the Gulf region, delaying cleanup efforts, affecting thousands of jobs, and endangering the lives of all nearby wildlife.

See also BPGlobalPR on Twitter.

Safety is our primary concern. Well, profits, then safety. Oh, no- profits, image, then safety, but still- it’s right up there.

This weekend only! Come to bp to top off your tank and we will top off your tummy with some free $10 blackened shrimp! #bpcares

The FT has a profile of Farouk al-Kasim, an Iraqi who immigrated to Norway as a young man and helped the country set up their sizeable oil concern. His biggest contribution was helping Norway cope with the discovery of oil.

Poor countries dream of finding oil like poor people fantasise about winning the lottery. But the dream often turns into a nightmare as new oil exporters realise that their treasure brings more trouble than help. Juan Pablo Perez Alfonso, one time Venezuelan oil minister, likened oil to “the devil’s excrement”. Sheikh Ahmed Yamani, his Saudi Arabian counterpart, reportedly said: “I wish we had found water.”

Oil expertise was so scarce in the Nordic country when al-Kasim arrived that an innocent query at the Ministry of Industry turned into a job that paid him more than Norway’s prime minister. (via gulfstream)

From The Last Traffic Jam in The Atlantic.

Unless we exercise foresight and devise growth-limits policies for the auto industry, events will thrust us into a crisis that will lead to a substantial erosion of our domestic oil supply as well as the independence it provides us with, and a level of petroleum imports that could cost as much as $20 to $30 billion per year. (This in turn would produce a staggering balance-of-payments problem for the United States, and give the Middle Eastern suppliers a dangerous leverage over our transportation system as well.) Moreover, we would still be depleting our remaining oil reserves at an unacceptable rate, and scrambling for petroleum substitutes, with enormous potential damage to the environment.

And:

In short, common sense dictates that we begin a transition to policies designed to avoid an energy impasse that could cripple out transportation system and imperil our economy. We must set growth limits that will allow the automobile and oil industries to maintain economic stability while conserving our resources and preserving our environment. Of course, such a reorientation will require statesmanship as well as public pressure. It will not happen unless corporate self-interest yields to a responsible outlook that serves the broader interests of the nation as a whole. Above all, this shift requires a thorough redirection of the aims of these two industries.

Believe it or not, those words appeared in the magazine in 1972. These views would have seemed out-of-date and old fashioned just a year or two ago but now all those chickens are coming home to roost.

A list of fifty things being blamed on rising oil prices. Among them: pizza deliviery prices, weakened demand for wine, “gas rage”, and more foot patrol for police officers.

I wish this map of current US gas prices factored out the taxes included in the pump price. It seems like what the map mostly shows is the differences in taxes between states (PDF map) and not, for instance, how the distance from shipping ports or local demand affects prices. (via what i learned today)

The milkshake line from There Will Be Blood came from a transcript that PT Anderson found of the 1924 congressional hearings over the Teapot Dome scandal.

Anderson concedes that he’s puzzled by the phenomenon — particularly because the lines came straight from a transcript he found of the 1924 congressional hearings over the Teapot Dome scandal, in which Sen. Albert Fall was convicted of accepting bribes for oil-drilling rights to public lands in Wyoming and California.

In explaining oil drainage, Fall’s “way of describing it was to say ‘Sir, if you have a milkshake and I have a milkshake and my straw reaches across the room, I’ll end up drinking your milkshake,’ ” Anderson says. “I just took this insane concept and used it.”

(via observations on film)

The oil sands of Alberta have created an oil boom in the Canadian province.

And how much oil is there? Estimates bounced around for years until 1999, when Alberta got serious about determining its potential. Based on data from 56,000 wells and 6,000 core samples, the Energy and Utilities Board (EUB) came up with an astonishing figure: The amount of oil that could be recovered with existing technology totalled 175 billion barrels, enough to cover U.S. consumption for more than 50 years. With the new math, Canada slipped quietly into second place behind Saudi Arabia’s 265 billion barrels in oil reserves, followed by Iran and Iraq.

Edward Burtynsky took some photos of the oil sands to accompany the piece. (thx, marshall)

Update: VBS.tv did a report on the oil sands as part of the Toxic Series. Elizabeth Kolbert wrote about the oil sands for the New Yorker late last year; unfortunately only an abstract of the article is available online. (thx, meg, ben, sanj, and greg)

Daniel Day-Lewis is flat-out amazing in this film; I can’t think of when I’ve seen a better performance. But with this movie and No Country For Old Men, both of which top many people’s lists of the best movies of 2007, I found them really good but not great. Not sure why. Maybe I’ll have better luck with Juno or The Diving Bell and the Butterfly.

Trailer for There Will Be Blood, the first movie from PT Anderson in I don’t know how long. The flick stars Daniel Day-Lewis and is adapted from Upton Sinclair’s novel Oil! (via crazymonk)

The most enjoyable and interesting thing I’ve read in a week has to be this article about Wayne Gerdes (via bb). Gerdes is a hypermiler — a person who drives in an obsessive fashion in order to increase his vehicle’s fuel efficiency — and strikes me as someone that Errol Morris would be quite interested in doing a short documentary about. He’s refined his driving technique over the years to wring 59 MPG out of a plain Honda Accord and clocked over 180 MPG with a hybrid Honda Insight. Here’s a taste of how he drives:

“Buckle up tight, because this is the death turn,” says Wayne. Death turn? We’re moving at 50 mph. Wayne turns off the engine. He’s bearing down on the exit, and as he turns the wheel sharply to the right, the tires squeal-which is what happens when you take a 25 mph turn going 50. Cathy, Terry’s wife, who is sitting next to me in the backseat, grabs my leg. I grab the door handle. As we come out of the 270-degree turn, Cathy says, “I hope you have upholstery cleaner.”

We glide for over a mile with the engine off, past a gas station, right at a green light, through another green light — Wayne is always timing his speed to land green lights — and around a mall, using momentum in a way that would have made Isaac Newton proud. “Are we going to attempt that at home?” Cathy asks Terry, a talkative man who has been stone silent since Wayne executed the death turn in his car. “Not in this lifetime,” he shoots back.

At PopTech last year, Alex Steffen of WorldChanging told the crowd that cars with realtime mileage displays get better gas mileage. Turns out that’s how Gerdes got really interested in hypermiling:

But it was driving his wife’s Acura MDX that moved Wayne up to the next rung of hypermiler driving. That’s because the SUV came with a fuel consumption display (FCD), which shows mpg in real time. As he drove, he began to see how little things — slight movements of his foot, accelerations up hills, even a cold day — influenced his fuel efficiency. He learned to wring as many as 638 miles from a single 19-gallon tank in the MDX; he rarely gets less than 30 mpg when he drives it. “Most people get 18 in them,” he says. The FCD changed the driving game for Wayne. “It’s a running joke,” he says, “but instead of a fuel consumption display, a lot of us call them ‘game gauges’” — a reference to the running score posted on video games — “because we’re trying to beat our last score — our miles per gallon.”

If people could see how much fuel they guzzled while driving, Wayne believes they’d quickly learn to drive more efficiently. “If the EPA would mandate FCDs in every car, this country would save 20 percent on fuel overnight,” he says. “They’re not expensive for the manufacturers to put in — 10 to 20 bucks — and it would save more fuel than all the laws passed in the last 25 years. All from a simple display.”

Competition, even with yourself, can be a powerful motivator. I’m not convinced, however, that FCDs would improve gas mileage across the board. There are other games you can play with the display — the how-much-gas-can-I-waste game or the how-close-can-I-get-to-18-MPG game — that don’t have much to do with conserving fuel consumption. Still, next time I’m in a car with a mileage display, I’ll be trying out some of Gerdes less intensive driving techniques, including the ones he shares on this Sierra Club podcast (Gerdes’ interview is about 2/3 of the way through).

Tariffs on imported sugar and ethanol imposed by the US government keep our sugar expensive and is keeping the US from using more efficient methods of saving energy and, oh, by the way, helping the environment. This excerpt from the last two paragraphs of the piece is a succinct description of what’s wrong with contemporary American politics:

Tariffs and quotas are extremely hard to get rid of, once established, because they create a vicious circle of back-scratching-government largesse means that sugar producers get wealthy, giving them lots of cash to toss at members of Congress, who then have an incentive to insure that the largesse continues to flow. More important, protectionist rules flourish because the benefits are concentrated among a small number of easy-to-identify winners, while the costs are spread out across the entire population. It may be annoying to pay a few more cents for sugar or ethanol, but most of us are unlikely to lobby Congress about it.

Maybe we should, though. Our current policy is absurd even by Washington standards: Congress is paying billions in subsidies to get us to use more ethanol, while keeping in place tariffs and quotas that guarantee that we’ll use less. And while most of the time tariffs just mean higher prices and reduced competition, in the case of ethanol the negative effects are considerably greater, leaving us saddled with an inferior and less energy-efficient technology and as dependent as ever on oil-producing countries.

Maddening. Partisan politics is a not-very-elaborate smokescreen to distract us from this bullshit.

At PopTech a few weeks ago, Lester Brown, who has been a leading advocate of environmentally sustainable development for almost 30 years, spoke about the impact of the increasing production of ethanol. As more corn gets used for making automotive fuel, that reduces the amount of grain available for food production. As demand rises, so will the price…no matter what people are using the corn for, be it fuel or food. The countries that will really suffer in this scenario are those that import lots of grain for food.

When Brown said this, I immediately thought of Mexico. When you consider the food culture of Mexico, one of the first things to mind is corn. Corn (maize) was likely first domesticated in Mexico and remains the cornerstone of Mexican cuisine; in short, corn is far more Mexican than apple pie is American. In 1491, his excellent book on the pre-Columbian Americas, Charles Mann tells us that despite corn’s high status, Mexico is increasingly importing corn from the United States because it’s cheaper than local corn:

Modern hybrids are so productive that despite the distances involved US corporations can sell maize for less in Oaxaca than can [local farmer] Diaz Castellano. Landrace maize, he said, tastes better, but it is hard to find a way to make the quality pay off.

Those great tortillas you had at some local place while on vacation in Mexico? There’s an increasing chance they’re made from US corn. Mmm, globalizious! Of course, Mexican farmers are getting out of the farming business because they can’t compete with the heavily subsidized US corn and Mexico is losing control over one of their strongest cultural customs. Now that ethanol is changing the rules, there’s a bidding war brewing between Americans who want to fill their gas tanks and Mexicans who want to feed their children. Odds are the tanks stay fuller than the stomachs.

For reference, here’s what increasing ethanol production has done to the price of corn over the past three months:

And that’s despite a fantastic US corn harvest. The graph is from this article in the WSJ, which contains a quick overview of the effects that the growing ethanol industry might have.

Some notes on a presentation by Thomas Friedman, who I’ve somehow managed to unconsciously steer clear of. (Doesn’t help that his stuff is behind the NY Times paywall. If he really wanted to make the impact on this green stuff, he’d get the Times to move that stuff out in the open so us proles can link to it and discuss it.) Here are Friedman’s five reasons why “this is not your father’s energy crisis” (ie the 1970s):

1. With our energy consumption in the US, we’re funding both sides in the “war on terror”. Our oil consumption pays for terrorists and our taxes pay for the armed forces, etc.

2. The world is flat, globalization, opportunities to consume at first world levels are available to China, India, Russia, etc. And they’re seizing the day.

3. Clean power and green energy is the #1 growth industry of the 21st century.

4. What Tom referred to as the First Law of Petropolitics: the price of oil has an inverse relationship with the pace of freedom. Oil prices fall, freedom goes up; oil prices rise and Iran starts talking about the myth of The Holocaust.

5. The new economy companies (Friedman namechecked Google and Yahoo specifically) are going to drive clean power and green energy because every time you do a search on the web, it costs them a little bit of power and they are going to want to drive that price down.

He finished by saying that green has been marginalized as being sissy, liberal, and Unamerican, but Friedman says “green is the new red, white, and blue”.

The Oil We Eat. “With the possible exception of the domestication of wheat, the green revolution is the worst thing that has ever happened to the planet.”

Update: Here’s a Wired article on super organics, smartly breed foods that will “that will please the consumer, the producer, the activist, and the FDA”. (thx, andy)

The Competitive Enterprise Institute has produced two TV ads critical of the global scientific and political consensus on global warming. “Carbon dioxide. They call it pollution. We call it life.” CEI is funded in part by energy companies, but I guess they’re not that well funded because that’s some of the most laughable propaganda I’ve ever seen. (thx, kyle)

Greg Saunders has a suggestion for a simple Democratic ad campaign for the midterm elections consisting of three graphs: gas prices, oil company stock prices, and oil company campaign contributions.

Photos of the Bangladesh shipbreaking yards by Brendan Corr. Strict environmental laws in the Europe and the US make “recycling” these ships there difficult, so US and European companies outsource the salvage to Bangladesh, where laws are looser. Compare with Edward Burtynsky’s photos of the same. (thx, malatron)

Update: Article from The Atlantic about shipbreaking (thx, john) and a soon-to-be released book called Breaking Ships (thx, john #2).

Older posts

Stay Connected